Researchers have discovered a relatively new way to distribute malware that relies on reading JavaScript code stored in an obfuscated PNG file’s metadata to trigger iFrame injections.

The technique makes it highly unlikely a virus scanner would catch it because the injection method is so deeply engrained in the image’s metadata.

Peter Gramantik, a malware researcher at Sucuri, described his findings in a blog post Monday.

This particular iFrame calls upon a simple JavaScript file, jquery.js (below) that loads a PNG file, dron.png. Gramantik notes that while there was nothing overly odd with the file – it was a basic image file – what did catch him off guard was stumbling upon a decoding loop in the JavaScript. It’s in this code, in this case the strData variable, that he found the meat and potatoes of the attack.

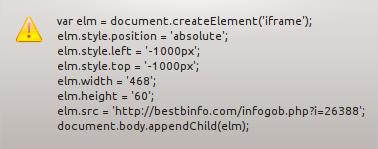

The iFrame calls upon the image’s metadata to do its dirty work, placing it outside of the browser’s normal viewing area, off the screen entirely, -1000px, according to Gramantik. While users can’t see the iFrame, “the browser itself sees it and so does Google,” something that if exploited could potentially lead to either a drive-by download attack or a search engine poisoning attack.

The payload can be seen in the elm.src part (above) of the data: A suspicious-looking, Russian website that according to a Google Safe Browsing advisory is hosting two Trojans and has infected 1,000-plus domains over the last 90 days.

The strategy isn’t exactly new; Mario Heiderich, a researcher and pen tester at the German firm Cure 53 warned that image binaries in Javascript could be used to hide malicious payloads in his “JavaScript from Hell” con talk back in 2009.

Similarly, Saumil Shah, the CEO at Net-Square described how to embed exploits in grayscale images by inserting code into pixel data in his talk, “Deadly Pixels” at NoSuchCon in Paris last year and at DeepSec in Vienna the year before that.

Still though, it appears Gramantik’s research might be the most thought out example of the exploit to date using this kind of attack vector.

Regardless of how new or old the concept is, Gramantik stresses that it could still be refined and extended to other image files. Because of that the researcher recommends that going forward, IT administrators better understand what files are and aren’t being added and modified on their server.

“Most scanners today will not decode the meta in the image, they would stop at the JavaScript that is being loaded, but they won’t follow the cookie trail,” Gramantik warns in the blog.

Steganography, the science of hiding messages, oftentimes by concealing them in image and media files has been used in several high profile attacks in the past. The actors behind the MiniDuke campaign in 2013 used it to hide custom backdoor code while Shady Rat was found encoding encrypted HTML commands into images to obscure their activity in 2011 .