SINT MAARTEN—In the waning moments of his 2016 talk at the Security Analyst Summit, Thomas Rid had a drop-the-mic moment when he disclosed there were likely links between the infamous Moonlight Maze cyberespionage operation of the mid- and late-1990s and the modern-day Turla APT.

Today during this year’s annual Kaspersky Lab conference, Rid, along researchers Costin Raiu and Juan Andres Guerrero-Saade of Kaspersky Lab, presented more evidence that could ultimately and definitively connect one of the earliest cyberespionage campaigns on record to the Russian-speaking APT proficient in stealing secrets from sensitive Western targets through the use of hijacked satellite links, watering hole attacks, a host of covert backdoors, and advanced malware.

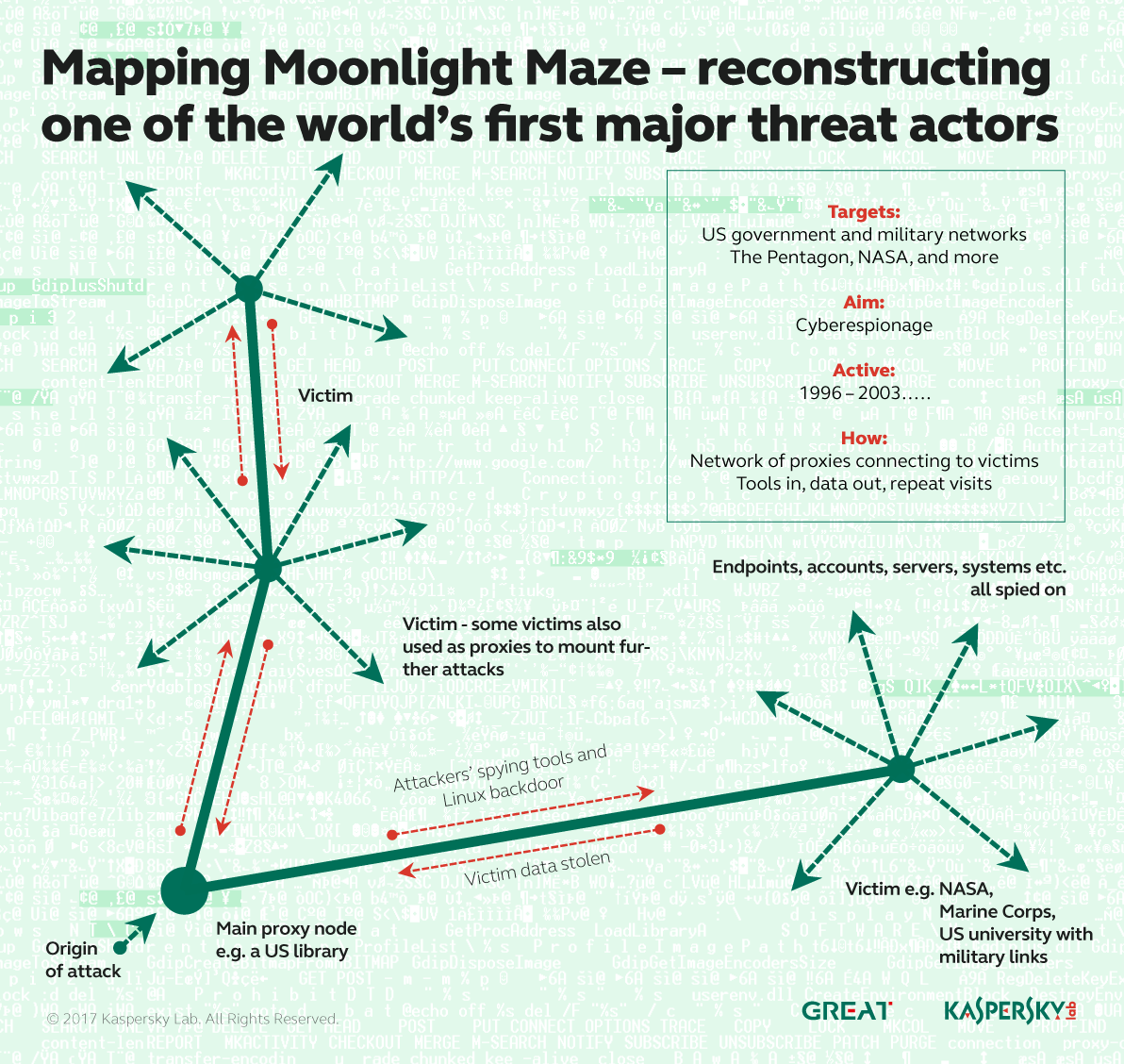

Moonlight Maze is the name given to a vast online spying operation that targeted a number of critical U.S. government agencies, including the Pentagon, NASA and the Department of Energy. For its time, which dates back to 1996, Moonlight Maze was a standard-bearer for cyberespionage.

There is a gap, however, between the early days of Moonlight Maze and its attacks tailor-made for UNIX systems such as Sun Solaris, and today’s Turla APT and its focus on Windows. The researchers believe that missing link lies in the Penguin Turla attacks of 2011 disclosed by Kaspersky Lab in 2014. Penguin Turla targeted Linux machines with a backdoor based on the open-source LOKI2 backdoor that was released in Phrack magazine in September 1997.

“We have not seen that tool leveraged by any modern attacker,” Guerrero-Saade said. “However, it’s what the Penguin Turla backdoor was based on. It’s an interesting tool and it obviously was a favorite of the Moonlight Maze attackers.” Guerrero-Saade said of the 45 Moonlight Maze binaries Kaspersky Lab has collected, nine of them were examples of the LOKI2 backdoor.

If this is the definitive link between Moonlight Maze and Turla, it would put the Russian-speaking APT among the elite nation-state attack groups, alongside the Equation Group, in terms of capabilities and durability. Equation Group, considered by many to have strong ties the U.S. National Security Agency, is the only other known APT active in 1996.

“This places Turla in another league altogether,” Guerrero-Saade said.

While Guerrero-Saade stopped short of saying Moonlight Maze is Turla, developments such as this and other forensic artifacts recovered in the past year give the researchers growing confidence. It also is “terrifying” to Guerrero-Saade that a 20-year-old hacking tool still has relevance and was being used in 2011—and probably beyond to today—in high-end attacks against modern computers.

“This speaks to the state of Linux security and the lack of awareness—and even hubris—that goes into some Linux system administration, an ill-advised approach for government and corporate settings,” Guerrero-Saade said. “These guys (Moonlight Maze) didn’t have to play the cat-and-mouse game with antivirus companies or rewrite their toolkit 30 times to get it through VirusTotal and still hope it works. It’s terrifying to see that the evolved Penquin Turla samples are based on 20 year old code and still linked to libraries built in 1999-2004 and they still work on modern machines. You’d never see that on Windows.”

The detective work behind uncovering not only the tools used by Moonlight Maze, but also their adaptability and expertise in attacking a lineage of UNIX, Linux and Windows machines, was equally fascinating.

In and around Rid’s 2016 SAS presentation, the researchers were determined to pursue this story and connect as many dots to build a forensic timeline from Moonlight Maze’s early UNIX and Solaris toolkits, through Penguin Turla for Linux, up to today’s modern Windows attacks. The possible link that is the LOKI2 backdoor, for example, was compiled for Linux versions 2.2.0 and 2.2.5 that were released in 1999, while linked binaries such as libpcap and OpenSSL were from the early 2000s. These relatively ancient artifacts were found in attacks ranging from 2011 to one last month against a target in Germany.

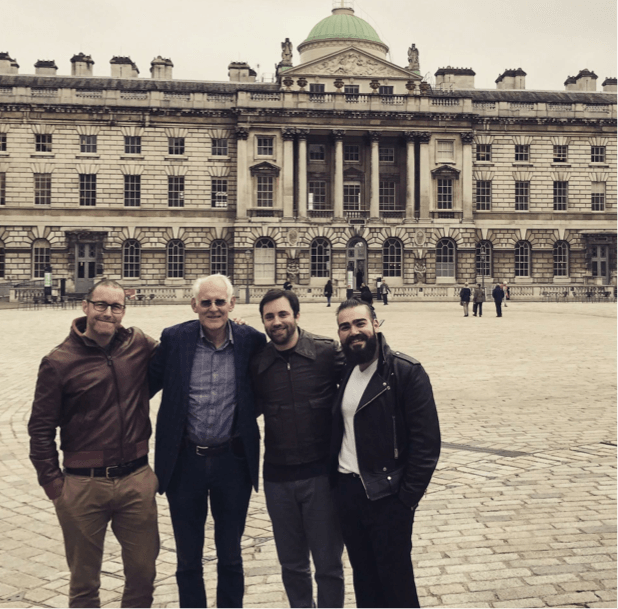

Finding the original artifacts required a bit of good fortune, and that came from a system administrator in the U.K. named David Hedges (second from the left, below) who had many years before turned a compromised Solaris server against the Moonlight Maze operators. In cooperation with the Metropolitain Police in London and the FBI, Hedges logged every keystroke happening on the server, which was being used as a relay to attack sensitive targets in the U.S. Hedges also saved six months worth of binaries and archives moving through the server, which was called HRTest. The researchers were able to find Hedges, today semi-retired, because of a redaction error in an FBI FOIA release. Hedges said the server was still up and running and he shared access to logs, as well as logs created by the Moonlight Maze attackers, and a toolkit with 43 binaries used in their attacks.

“It was really impressive. We were drooling at what we had found and could finally get our hands on,” Guerrero-Saade said. “David was careful not to get his hands on exfiltrated stuff, even if it was 20 years old. But the samples and logs were a treasure trove. The more we looked at it, the more we could see connections through this proxy–it was stunning how small a sliver of the actual attack we could see.”

The next angle the researchers are pursuing is a toolkit called Storm Cloud that Moonlight Maze used after the first attacks became public in 1999. Storm Cloud was also made public four years later, and it too relied on the LOKI2 backdoor to attack targets such as the U.S. Department of Defense’s high-performance computers doing missile testing projections.

“We’re really trying to push the crowdsourcing element to this,” Guerrero-Saade said. “Thomas’ first talk helped us find David and more about Moonlight Maze. We need help. We need another David Hedges, someone with access to the Storm Cloud artifacts to really solidify this link.”