SAN FRANCISCO–The crown jewel of North America’s critical infrastructure is its electric grid. A successful cyberattack on it would be devastating. But according to Marcus Sachs, CSO with the North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC), fears of a cyberattack are overblown.

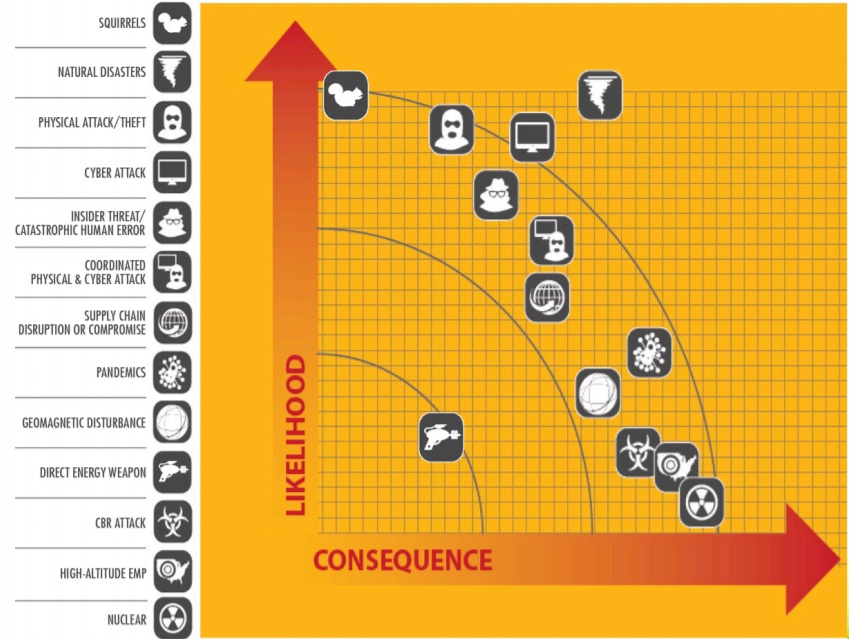

Sachs told RSA Conference attendees on Thursday that squirrels, birds and snakes are currently a bigger threat to the power grid than cyber adversaries. During a session on securing the North American Electric Grid, Sachs said as long as the threat is greater than zero, focus on protecting the grid will always be important. But, he said current priorities are on high impact and high consequence threats that don’t currently include cyberattacks.

“Security is extremely important to us. We have to keep the lights on. There are multiple threats. Cyber is one and physical is another,” he said. “Yes, we have a few mouse clicks here and there – but the real threat is Mother Nature and humans doing stupid stuff.” Topping concerns are threats such as natural disasters, physical attacks and theft of equipment such as copper wiring from utility power substations.

Concerns over cyber threats to the North American power grid have been a popular topic ever since hackers managed to cut power to 200,000 Ukrainians in 2015. The incident sparked a number of government inquiries from the Department of Homeland Security and FBI into the preparedness for potential cyherattacks.

According Sachs, the Ukrainian outage also pushed NERC to take a hard look at what lessons could be learned from the attack. “Ukraine is a lot like the U.S. power grid, sharing many of the same physical and technical attributes,” he said. The saving grace for the North American electric grid, making it exponentially less vulnerable than Ukraine’s, is the hodgepodge of technologies used in the grid’s 55,000 power substations.

“What makes Ukraine different from U.S. is their grid is synchronous and lacked the type of diversity and separation of infrastructure that we have in the North America,” Sachs said.

In the case of the Ukraine cyberattack hackers sent a phishing email to a power company admin that contained an Excel spreadsheet with a malicious macro, Sachs said. Once the macro was executed hackers were able to steal credentials from the machine. It’s been disputed, but general consensus believes that malware used was developed by the BlackEnergy APT group.

Because Ukraine’s system was so homogenized, Sachs said, hackers were able to access three additional substations with stolen credentials. Next, hackers used remote desktop control software to access three admin machines at three separate power company offices and simply turned off a number of electric substations that caused the blackout.

“Here in North America, we encourage diversity. No two substations are the same no two companies run their infrastructure the same. It’s all over the place here. In the Ukraine it’s homogenous. If you find a mistake one place, you can probably find the same mistake somewhere else; and that’s a problem,” he said.

NERC’s Critical Infrastructure Protection Committee (CIPC) coordinates NERC’s security initiatives that include assessing ongoing physical and cyber security threats. Another of CIPC’s key functions is developing, reviewing, and revising security guidelines that include cyber.

“The fact is we have built resiliency into the grid to counteract physical and cyber threats. If we get into a cyber situation, the same resiliencies and the same countermeasures that exist for physical threats will kick in and protect the grid. If the grid goes down – be it a cyberattack or natural disaster – we can get it back and up running again in minutes,” Sachs said.

Not all share Sachs optimism. Just last year at 2016 RSA Conference U.S. Cyber Command’s Adm. Michael Rogers said it’s a matter of when not “if” a nation-state executes a successful cyberattack against the U.S. critical infrastructure impacting the electric grid.

Meanwhile, jitters remain high. In December, a false report of a Russian cyberattack on a Vermont power utility was briefly the center of a geopolitical scandal.