LAS VEGAS—Hackers at DEF CON last week made quick work of finding vulnerabilities in electronic pollbooks and voting machines, needing just 90 minutes to find exploitable flaws in every piece of voting equipment.

More than 30 machines were available for hackers to crack at the conference’s Voting Machine Hacker Village, ranging from vendor equipment Diebold TSX, WinVote, ES7S iVotonic, and Sequoia AVC Edge. All of the systems were compromised in some way, said event co-coordinator Matt Blaze, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania and election security expert.

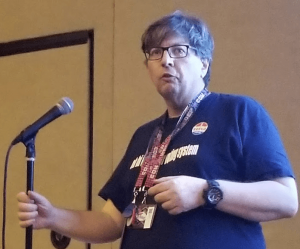

“What surprised me was how quickly the community was able to jump in and discover and exploit the vulnerabilities in these machines. We knew they could be exploited, we just didn’t know easily a broad community with this kind of expertise would be able to accomplish it,” said Blaze, below, in an interview with Threatpost Monday.

The first and easiest hack was found in a decommissioned WinVote system running an unpatched version of Windows XP that used WEP-based Wi-Fi.

“This one was particularly easy, because it had wireless access. I don’t need physical access to the machine. As long as you were within proximity, you would be able to access these machines and nobody would notice,” said Carsten Schuermann, associate professor at IT University of Copenhagen working in the Democracy Technology program, who hacked the system.

He said the WinVote system was used between 2002 and 2014 in many parts of the United States election system. Using Kali Linux, Schuermann said he scanned the environment to see what kind of vulnerabilities were available on the voting machine that was running an unpatched version of Windows XP. In under two hours, he was able to “own” the voting machine.

“We can install Pac-Man on it. We can delete all the data or change vote totals. We can turn off the machine if we want. Or we can install malware, so when the USB storage device is taken out with vote totals it can infect anything it plugs into,” he said.

Blaze said all of the electronic voting machines in the United States have weaknesses of some kind in them. “What the Voting Village experiment demonstrated was just how quickly someone can take a never-before-seen machine and find ways to exploit it from top to bottom,” he said.

Many researchers who examined voting machines in the past dismissed vulnerabilities as being impractical, too difficult to find, or would require specialized expertise to exploit.

A sampling of teams at the Voting Village said they were able to easily access firmware or device storage and manipulate or destroy pollbook or voting data. One team said an electronic pollbook they were dissecting used commodity storage cards that could easily be popped out or swapped.

Blaze acknowledges that hacking into systems might not always be stealth or practical in real-world elections. But, he said, hacking a voting system or pollbook that contains voter data isn’t always the chief objective.

“The goal isn’t always changing votes to steal an election. It’s often to bring into question the vote itself, to create disorder or cast doubt on the legitimacy of the person who won.”

Blaze said the 2016 election was the first large-scale attempt to influence a U.S. election and didn’t include targeting of electronic voting machines.

“Why, given how vulnerable these machines are, would an attacker not use voting machines as an attack vector?” Blaze said. “The reason is, as easy as it is to attack a voting system, it’s even easier to mail your malware to an election official wrapped inside of a .Doc file.”

Last month, a leaked National Security Agency report claimed days before the U.S. presidential election attackers targeted a U.S. voting software supplier in a spear-phishing campaign that contained a malware-laced Word document.