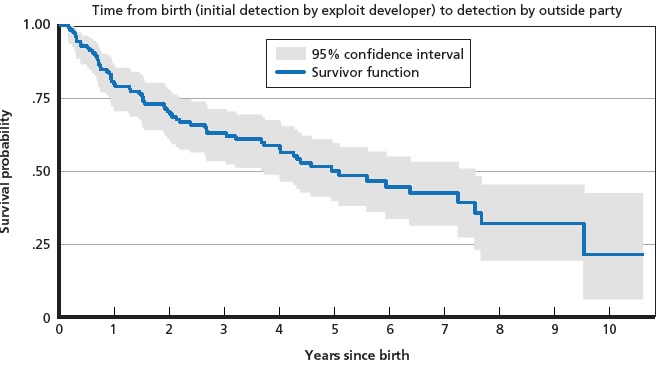

It takes less than a month for most zero-day exploits to be developed, and about a quarter of those previously unknown and unpatched vulnerabilities will go undiscovered and undisclosed to the vendor for an average of 9.5 years. And the odds two hackers will find the same zero day are slim.

RAND Corporation analyzed 200 zero-day vulnerabilities, 40 percent of which it says are not publicly disclosed, and published the results this week in an extensive report titled “Zero Days, Thousands of Nights: The Life and Times of Zero-Day Vulnerabilities and their Exploits.”

“This is a first-ever look at zero days that isn’t based on manufactured data or vulnerabilities that have already been discovered,” said Lillian Ablon, lead author of the study. “Unique to this report is access to privately known but not publicly disclosed zero day vulnerabilities.”

In its report, RAND teamed with several firms that agreed to share share zero day intelligence on conditions of anonymity. Ablon said she hopes to provide insights into the exploit development industry and help inform ongoing policy debates regarding stockpiling and vulnerability disclosure.

The report focuses on what is driving the cost of zero days, the development of vulnerabilities within the black, gray and white hat hacker community, and the lifespan and management of zero-day exploits. RAND researchers define zero day vulnerabilities as “exploitable vulnerabilities that a software vendor is unaware of and for which no patch or fix has been publicly released.”

Ablon said, the private zero day data provided to RAND offered insights into understanding things such as zero day collision rates–the likelihood two people will find the same vulnerability.

“We were surprised to find that there were such low collision rates,” Ablon said.

“For a given stockpile of zero-day vulnerabilities, after a year approximately 5.7 percent have been discovered by others,” the report revealed. Accounting for low collision rates are a diversity of research tools and methodologies used by researchers coupled with the fact private zero day hunters are looking for different vulnerabilities than those hunting for vulnerabilities to share as public knowledge.

In its study, RAND looked at a zero days that target a variety of platforms, including Linux, macOS, Windows and other Unix-based systems. But researchers said, because of insignificant data, none could be determined as the most targeted. It also noted, of the 200 zero day vulnerabilities examined 40 percent were publicly unknown and the other 60 percent either known or somewhere in between “dead” and “alive.”

“There are still other vulnerabilities that are quasi-alive (like a zombie), because they can be exploited in older (software) versions but not the latest version of a product. These ‘code refactor’ vulnerabilities get removed through revisions to the code, without being discovered or publicly disclosed as security vulnerabilities. And because of the dynamic nature of vulnerabilities, something exploitable one day may not be the next (and vice versa),” according to the report.

For that reason Ablon said, “boiling the argument down to whether (zero day) vulnerability is ‘alive’ versus ‘dead’ is too simplistic and could create a barrier for vulnerability-detection efforts.”

Zero-day development, meanwhile, has a median time of 22 days, according to the report, and a maximum of 2.5 years.

“At the most basic level, any serious attacker can always get an affordable zero-day for almost any target. However, other tangible costs (acquiring products to find the vulnerabilities in, setting up test infrastructure, maintaining and porting the exploit to work on multiple versions, renting work space, etc.) and intangible costs (premium of a high-demand, low-supply product, etc.) can cause the price to rise dramatically,” according to the report.

RAND found that 71 percent of the 200 exploits it looked at were developed in 30 days, 31.44 percent were developed in under a week, and 10 percent took more than 90 days.

When it came to cost, researchers found zero day pricing wasn’t based just based on labor and complexity involved in creating the exploit, but rather demand. “Value can come from a vulnerability’s uniqueness (e.g., if it is the only vulnerability found in a specific product) or the need and timeline of the customer,” according the report.

Interestingly, vulnerabilities purchased from external third parties had a shorter average lifespan of 1.4 years, according to the report. One quarter of vulnerabilities become publicly known within 1.5 years. Another quarter remain undiscovered for more than 9.5 years.

“Vulnerabilities have a surprisingly long shelf life,” Ablon said. “Quite a few of the vulnerabilities remain in older code which suggests researchers shouldn’t scrap going back and checking older software.”

Ablon said low zero day collision rates coupled with long shelf life could help make the argument as to why the practice of vulnerability stockpiling, which if fraught with tradeoffs, particularly for governments, may be a valid option.

“If there is a low chance someone else is going to find your zero day and the next one may be hard to find or expensive there seems to an argument for stockpiling,” she said. “But on the flip-side, even a more than one percent chance of a collision could make the argument for disclosing and why stockpiling wouldn’t be an option.”

Pricing for zero days, the report said, can vary from “unicorn” exploits such as uncommon iPhone full-chain exploits that cost $1 million. Researchers admit that zero day pricing is still largely unknown and can fluctuate immensely based on who is buying from what market.

“In general, for any market, payment structure generally comes down to a few factors: how easy or hard it is to find the vulnerability (if hard, payout is greater), how many other vulnerabilities have been found in the product (if few, then vulnerabilities may be sparse, and the payout is greater), and the impact (if an exploit can go further than just remote code execution, but also bypass a mitigation, escape a sandbox, or remotely jailbreak [for mobile devices], then the payout is greater),” according to the report.

The RAND research, Ablon said, hopes to establish an initial baseline metrics for the U.S. government and researchers as they grapple with whether they should retain zero day software vulnerabilities or disclose them so they can be patched.

“Cybersecurity and the liability that might result from attacks, hacks, and data breaches using zero-day vulnerabilities have substantial implications for U.S. consumers, companies, and insurers, and for the civil justice system broadly,” the report stated.