Attackers have taken to Facebook Messenger with a combination of social engineering and malicious JavaScript to spread adware, something that’s likely earning them a small chunk of change in the process.

David Jacoby, a senior security researcher with Kaspersky Lab’s Global Research & Analysis Team, said he spotted an attack he believes is part of a greater campaign earlier this week on the social media platform.

Jacoby wrote Thursday in a blog post to Securelist that code behind the campaign is “advanced and obfuscated,” and uses “tons of domains to prevent tracking” and earn clicks.

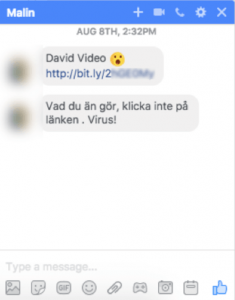

The message uses the victim’s name and the word “video” in order to entice them to click through to a shortened bit.ly link in the message. If the victim does click through, they’re brought to a Google Docs page, which hosts an image from the victim’s Facebook Photo album.

The message uses the victim’s name and the word “video” in order to entice them to click through to a shortened bit.ly link in the message. If the victim does click through, they’re brought to a Google Docs page, which hosts an image from the victim’s Facebook Photo album.

Social engineering comes into play again on the Google Docs page. The photo has a transparent play button over it, rigged to look like a video. If the victim clicks on it, Jacoby says, it directs the victim to a series of websites, multiple domains the researcher calls a domain chain, and in turn adware.

“By doing this, it basically moves your browser through a set of websites and, using tracking cookies, monitors your activity, displays certain ads for you and even, in some cases, social engineers you to click on links,” Jacoby writes.

Jacoby says which sites victims are cycled through would depend on a few things, including which browser or operating system they’re using, which plugins or cookies they have installed, or their language/geolocation.

While on Firefox, Jacoby was sent to a site with a phony Flash Player update notice and in turn a Windows executable—flagged as adware. On OS X he was hit with the same fake Flash page, and adware hidden in a .dmg file. On Chrome, he got a fake YouTube page that went onto download what appears to be a malicious Chrome extension.

Jacoby wrote that while it’s been a while since he’s seen an adware campaign leveraging Facebook, what’s more surprising is the fact that it’s using Google Docs to serve up landing pages customized for each victim.

The researcher adds that it’s unclear – at least for now – how the adware is spreading through Facebook Messenger but that his research is ongoing. Jacoby hints it could be due to stolen credentials, hijacked browsers, or clickjacking.

Frans Rosén, a knowledge advisor at the Swedish security firm Detectify, suggested on Twitter at least one vector of the campaign is using breached Chrome extensions to do so. Rosén posted a copy of the malicious JavaScript injected via an extension to Facebook, on Wednesday afternoon.

Here's the script injected to Facebook using breached Chrome Extensions as one vector, currently targeting Messenger https://t.co/BfuS8bAUXD

— Frans Rosén (@fransrosen) August 23, 2017

While there’s no actual malware being dropped on the victim’s machine, Jacoby says, adware is downloaded. On top of that the attackers are likely making money when victims are cycled through ads via the attack, he adds.

“As far as I can see no actual malware (Trojans, exploits) are being downloaded but the people behind this are most likely making a lot of money in ads and getting access to a lot of Facebook accounts.”

When reached Thursday a spokesperson for Facebook Messenger said the service has a number of methods in place to prevent malicious links from popping up in chats.

“We maintain a number of automated systems to help stop harmful links and files from appearing on Facebook. If we suspect your computer is infected with malware, we will provide you with a free anti-virus scan from our trusted partners. We share tips on how to stay secure and links to these scanners on facebook.com/help,” Facebook said.

Facebook last summer fixed a vulnerability in its Messenger app that could have let an attacker access and modify chats. Researchers with Check Point Software Technologies said at the time that if a victim was persuaded to click on a malicious link, they could start a a malware download or establish a connection to an attacker’s command and control server.

Facebook refuted several of those claims but fixed the bug regardless in June 2016.

Zerodium, an exploit acquisition vendor, put a premium price on Facebook Messenger zero days earlier this week. The Washington, D.C.-based vendor said Wednesday it would pay $500,000 for researchers who report critical vulnerabilities in Messenger, along with Signal, WhatsApp, and iMessage to the company.

This article was updated at 3 p.m. EST with a statement from Facebook