When the long arm of the law reached in to arrest members of Anonymous’s senior leadership on Tuesday, speculation immediately turned to the identities of the six men behind the Guy Fawkes mask. With the benefit of hindsight, it turns out that many had been hiding in plain site, with day jobs, burgeoning online lives and – for those who knew where to look – plenty of clues about their extra curricular activities on behalf of the world’s most famous hacking crew.

When the long arm of the law reached in to arrest members of Anonymous’s senior leadership on Tuesday, speculation immediately turned to the identities of the six men behind the Guy Fawkes mask. With the benefit of hindsight, it turns out that many had been hiding in plain site, with day jobs, burgeoning online lives and – for those who knew where to look – plenty of clues about their extra curricular activities on behalf of the world’s most famous hacking crew.

An investigation by Threatpost found that two of the accused, Darren Martyn (aka “pwnsauce,” “raepsauce,” and “networkkitten,”) and Donncha O’Cearbhail, formerly known as Donncha Carroll (aka “Palladium”) sported outsize online footprints and made little effort to hide their affinity for hacking.

Darren Martyn a.k.a “pwnsauce” – Guns, DDoS and…OWASP?

Martyn, a biopharmaceutical chemistry student at the National University of Ireland Galway (NUIG), was charged this week with with two counts of computer hacking conspiracy after being arrested in January. He and alleged LulzSec accomplice Donncha O’Cearrbhaill were arrested in September, 2011 for an attack on the Website of the Irish political party Fine Gael that yielded contact details of 2,000 subscribers in January, 2011. Both counts carry a maximum sentence of 10 years in prison.

Online and phone inquiries by Threatpost revealed that Martyn to be something of a paradox: technically adept with a healthy professional life, but hiding a dark side that threatened, at any moment, to wash over him.

He made no secret of his interest in hacking and his affinity with Anonymous, the anarchic hacking group. His Facebook page listed famed computer hacker Kevin Mitnick and Metasploit creator HD Moore as inspirations and shellcode development, ethical hacking, hacking computers and even “denial of service” under his ‘Activities and Interests.’

A Facebook photo gallery dating to December 2010 contains nearly a dozen screen capture images related to Anonymous’ “Operation: Payback,” a campaign the group launched at the end of 2010 in opposition to Mastercard, Visa and Paypal for censoring donations to Wikileaks. The gallery, entitled “Payback – Anonops DoS” shows captured images of Web sites like Paypal.com, Mastercard.com, Visa.com and Senate.gov offline, presumably after getting hit with a distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack launched by Anonymous.

Martyn used his Facebook profile to chronicle his interest in firearms and explosives, as well as hacking. His Facebook is littered with images of airsoft guns, ammunition and diagrams that describe how to make detonators for certain kinds of fireworks. For those who might doubt his passion for explosives, Martyn’s chose “Hexamine.Dinitrate” for his Facebook URL – the name of an explosive made with hexamine, acetone and nitric acid. (A separate Facebook profile, apparently also belonging to Martyn, can be found here.) Outside of Facebook, the chemistry major also made frequent posts regarding chemistry and explosives to ScienceMadness’ a message board under the name -=HeX=-.

In other areas, however, Irish man (who was reported to be 25, but claimed to be 19), seemed to be on his way to bigger and better things. He was a local chapter leader of the Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP) in Galway, Ireland. He spent some of his free time with a small collective of computer researchers with Insecurety Research, under the name “infodox.”

With the revelation of the charges against him, however, Martyn’s professional aspirations appear to have changed. A report by Reuters on Friday said that Martyn had resigned that position last week.

“It’s about laws and ethics, and people have to determine whether they want to follow the speed limit, follow the law,” Thomas Brennan, who is a director of OWASP’s parent group, told Reuters. “We have the same skill set as the bad guys, but the only difference is ethics.”

Martyn, himself, appears contrite, as well. Communicating through a personal Twitter account @info_dox, he advised a friend “Don’t go blackhat, it is not worth it. Seems fun at the time but the consequences are not.”

Martyn now calls himself a “reformed blackhat,” in his Twitter “About me” section and on a forum Tuesday claimed he had been trying to “rehabilitate” himself by contributing to the open source security community since he was arrested.

Donncha O’Cearbhail a.k.a. “Palladium” – An Olympian Programmer With High Ideals

Formerly known as Donncha Carroll, Donncha O’Cearbhail was best known to the World by his handle, “Palladium.” O’Cearbhail, the 18 year-old son of County Offaly Council member, John Carroll, was reportedly arrested in September and, like Martyn, accused of hacking into and crashing the website of Ireland’s Fine Gael political party. The attack reportedly lasted some four hours and resulted in the defacement of Fine Gael’s homepage.

O’Cearbhaill was eventually released after a law enforcement searched his home in Birr, Ireland and the seizure of a number of digital storage devices. Reports indicate that this investigation was linked to the larger international investigation of the hacking group Anonymous, who took credit for the attack. Reports also claim that authorities found chemicals that can be used to manufacture Ecstasy during the raid.

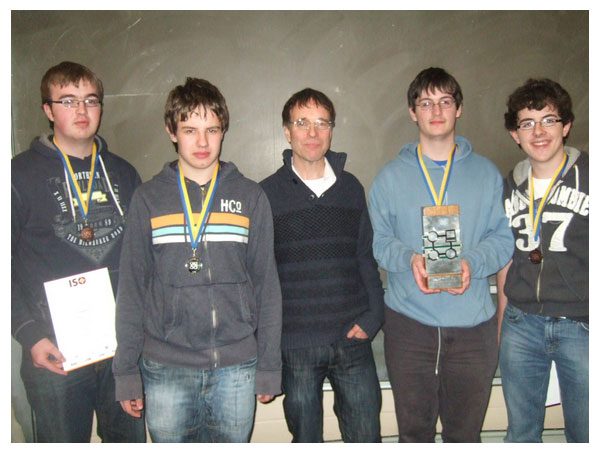

Like Martyn, O’Cearbhaill was an academic achiever with a knack for technology. At the time of his arrest, it appears that O’Cearbhail was attending the renowned Trinity College in Dublin where he planned on graduating with a degree in Medicinal Chemistry in 2015. He was recognized by the Irish Science Olympiad as a talented young computer programmer while he was a student at St. Brendan’s Community School in County Offaly. And O’Cearbhaill was a finalist in the Irish Computer Programming Olympiad three years running, winning the silver medal in 2010 and the bronze medal in 2011. In 2010 and 2011, he went on to compete at the International Informatics Olympiad in Thailand, finishing 135th and 127th respectively.

An avowed Socialist, O’Cearbhaill’s Facebook profile is spiced with quotations by Argentine Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara and British Parliamentarian and IRA member Bobby Sands, who died on a hunger strike protesting British policies in Northern Ireland in 1981. And, like other LulzSec members, notably Hector Monsegur, a.k.a. “Sabu,” O’Cearbhaill had an affinity for Julian Assange and Wikileaks.

Also like his compatriot, Darren Martyn, O’Cearbhaill’s interest in the doings of Anonymous and LulzSec was no secret. He used his personal Twitter account to pass along news of announcements from the group and press coverage of various operations. In mid-February, O’Cearbhaill fired off a series of tweets to a number of tech companies, including VodaPhone, about some security research he was doing on broadband routers.

However, like many other Anonymous members, personal and professional – black hat and gray – mixed seamlessly in O’Cearbhaill’s life, and it is unclear if any of the companies ever responded or what his intentions were, but other tweets indicate that O’Cearbhaill had a legitimate interest in what many would consider white-hat hacking. Calls to O’Cearbhaill’s father were not returned.

The wealth of clues about the two LulzSec members confirm what many experts in computer forensics have long been saying: that the proliferation of social networking and the increasing number of hours young people spend online makes it very difficult to maintain anonymity.

Speaking to an audience of law enforcement officials in New York City in January, Aaron Barr, the former CEO of Anonymous victim HBGary Federal, said that free and open source tools make it easier than ever to mine the rich seams of public data online on sites like Facebook, Twitter and other social networks to build profiles of cyber criminals, hacktivists and other persons of interest.

Barr incurred the wrath of Anonymous after he promised to identify key members at a San Francisco security conference in early 2011. While investigations still rely heavily on subpoena powers, Barr highlighted the ways that publicly accessible information and free and open source tools can be used to analyze patterns of online behaviors, make connections between seemingly different online personas and build detailed profiles of suspects and known criminals.