It was December 8, 2000 – the waning days of the Clinton Administration. Richard Clarke, a member of President Clinton’s National Security Council, was addressing attendees at SafeNet 2000, a conference sponsored by Microsoft Corp. that brought together computer security experts from around the country to talk about ways to increase cooperation around cyber security.

The bitter and contested November election was still hanging in the balance. (The Supreme Court wouldn’t issue its ruling in Bush v. Gore, the controversial case that effectively decided the election for four more days.) Accordingly, Clarke struck a neutral tone with the audience gathered. According to contemporary press accounts of the address, he tailored his remarks to “the next president” (whomever that might be) and said the events of the election proved that “statistically improbable events can occur.”

After that, however, Clarke’s remarks became more pointed. “It may be improbable that cyberspace can be seriously disrupted, it may be improbable that a war in cyberspace can occur, but it could happen,” he’s quoted as saying. He continued, predicting that the next president would, after taking office, learn that “several nations have created information warfare units that could be used to stage attacks against the U.S…These organizations are creating technology to bring down computer networks. Some are doing reconnaissance today on our networks, mapping them,” he warned.

For Clarke, this was not new material. Like a modern day Cassandra, he had been sounding the alarm about what he termed a “digital Pearl Harbor” for much of that year, as he tried to raise awareness in the public and within the beltway about the potential for devastating cyber attacks in future conflicts.

The audience at that year’s SafeNet Conference may have been sympathetic to Clarke’s view of things, but history had other plans. In less than a year, terrorists using weapons no more sophisticated than box cutters and portable GPS devices would hijack and crash four airliners, killing thousands in the largest attack on American soil since the Civil War.

The attacks, which happened ten years ago tomorrow, altered U.S. domestic and foreign policy in ways that are too numerous to count. But one of the more important, for the country’s long term security, was the way the physical attacks shifted the nation’s focus from cyber security and computer based threats to efforts to prevent physical attacks by foreign and domestic terrorist groups.

The impact of the attacks on Clarke, personally, were equally stark. Within a month, he was reassigned by Bush Homeland Security Director Tom Ridge to be Special Advisor to the President for Cyberspace Security within the newly created Department. It was a position he would resign from a little more than a year later, citing the new order of things; the brand new and unwieldy DHS now owned responsibility for cyber security, not the West Wing. President Bush had also signed the “National Strategy to Secure Cyberspace,” a blueprint for the U.S. government’s cyber security efforts that turfed most responsibility for securing the nation’s infrastructure to private sector firms and public-private partnerships.

Looking back, there’s a sense of dejá vú in Clarke’s warnings. Indeed, as news about rumored terrorist attacks, elevated “threat levels” and overseas wars have faded in recent years, they’ve been replaced, in part, with stories about the penetration of U.S. military and civilian government networks and the siphoning of priceless intellectual capital from U.S. firms – exactly the kinds of things Clarke was warning about more than a decade ago. As Threatpost reported this week, cyber security and hacking are on the front burner on Capitol Hill, after languishing for years as Congress focused on the threat posed by Al Qaeda and other terrorist groups.

What happened in the interim? It would be silly to say that cyberwar and threats from foreign governments disappeared. After all, there was plenty of discussion of the threat of digital attacks – terrorist or otherwise – in the immediate aftermath of the 9/11 attacks. The Bush Administration counted cyber attacks against military and civilian networks and critical infrastructure as top priorities.

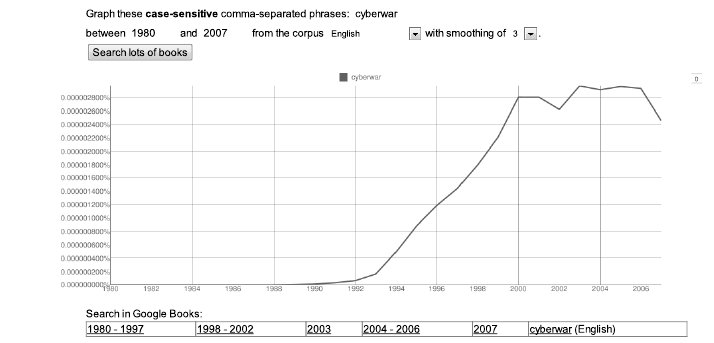

But its also true that the notion of a computer attack on a government network seemed tame to a nation with images of the smoking rubble of the Twin Towers, the Pentagon and the crash of United Airlines Flight 93 in Pennsylvania seared in its collective memory. In just one measure of the shift in focus, references in print to the term “cyberwar” dipped in the period after the 9/11 attacks for the first time ever, suggesting the way that the prospect of “cyberwar” dimmed in the immediate aftermath of the terrorist attacks.

CNET’s Chief Political Correspondent Declan McCullagh summed up the zeitgeist quite well in a 2003 editorial. Writing just after the U.S. invasion of Iraq, McCullagh covered testimony by DHS Secretary Ridge about cyber security before a House budgetary committee. Having quoted Ridge saying that cyber terrorists were just as dangerous as physical terrorists before, he wonders aloud:

“What is this guy thinking? Last I checked, it was physical terrorists who bombed the Marine barracks in Lebanon, who attacked the U.S.S. Cole, who took out the Oklahoma City federal building, and who suicide-bombed the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Wily-fingered hackers had nothing to do with it.”

McCullagh wasn’t exactly wrong, and he’s no lightweight when it comes to covering the tech space. But he may have been glossing over the real capabilities of those “wily fingered hackers” in his eagerness to point out the obvious: confronted with the prospect of a dirty bomb or a DDoS, most of us will take our chances with the DDoS. Whatever the case, McCullagh was merely echoing conventional wisdom: that the U.S. had bigger fish to fry than shadowy hackers crawling over our networks. The problem, of course, is that those wily hackers really were a serious problem – perhaps not as scary as bearded terrorists, but no less potent in their own way.

We know now that militaries around the world had gone to school on the U.S.’s offensive capabilities during the first Gulf War in the early 1990s and were, quite simply, amazed by the U.S. military ability to weave kinetic and cyber capabilities into a lethal and debilitating combination: disabling an enemy’s defenses while using satellite technology to deliver ordnance with frightening accuracy. Developing the ability to ward off such offensive attacks and to level the playing field against a much better armed U.S. military, then, became a top priority of countries such as China, which began building its cyber capabilities in earnest in the 1990s.

For U.S. enemies, we must assume, 9/11 was a godsend: distracting the U.S. political and military establishment from their traditional focused on nation-backed threats to terrorist groups, while siphoning critical personnel and resources away from things like cyber defense to focus them on ferreting out Al Qaeda’s leadership and interrupting terrorist plots.

All throughout the 1990s and accelerating in the post 9/11 period, foreign governments and groups working for them were establishing beach heads on critical U.S. government, military and defense industrial base (DIB) networks. By 2003, when news broke about coordinated attacks on the U.S. Defense Department, later dubbed “Titan Rain,” it was clear that those operations had moved into operational mode. Reports of the compromise of the U.S. classified data network, SIPRNet, and the attacks on Google and other private sector firms in 2009 merely showed that the scope of foreign cyber espionage and information gathering had moved well beyond low level lock jiggling on government, military and defense industrial base networks to highly sophisticated attacks against a wide swath of public sector and commercial networks.

“We weren’t awake. We didn’t see the deep penetration of the military and defense industrial base and economic engines,” said Alan Paller of the SANS Institute. “You can claim that was because government didn’t have its eye on the ball, but I’d argue that those other threats (aka “terrorists”) were far more realistic.”

Indeed, some of the changes wrought by the 9/11 attacks, while necessary, may have unwittingly aided the cyber espionage being carried out by other nations and by malicious insiders. In just the most obvious examples, the alleged leaking of hundreds of thousands of diplomatic cables by PFC Bradley Manning has been attributed, in part, to post 9/11 policies that promoted wide open data sharing between siloed civilian and military networks. Manning was no terrorist, but his ability to access highly sensitive State Department communications as a lowly Army PFC can be directly linked to a post Sept. 11 effort to break down barriers to sharing information.

Politics played a role, as well. In a political environment focused on smaller government and deregulation, neither the Bush nor the Clinton administrations was willing to use the power of the federal government to raise the bar on things like network security in the public and private spheres, nor to hold vendors’ feet to the fire to improve the security of IT systems they sold to the government. That began to change with the advent of the Obama administration.

The new president made cyber security a top priority: declaring the U.S.’s digital infrastructure a “strategic national asset” in 2009 and standing up the Pentagon’s U.S. Cyber Command in 2010. But on the issue of Uncle Sam throwing his weight around, which Paller at SANS has long advocated, it would be hard to find evidence of a big course correction on this score in the first two years of the Obama administration, either.

Fast forward to 2011 and both U.S. firms and Uncle Sam find themselves playing catch-up on cybersecurity in a big way. Having long ago established their beachhead, attackers are now confident enough to narrow their focus to specific technologies of interest, while also casting a wide net using low risk remote probes, to multi-staged attacks (think RSA SecurID) and sophisticated cons involving business partnerships and R&D agreements to vacuum up any data deemed useful to their national interest, or to undermining the U.S. military and political advantage. All the while, the government must fight a rear-guard action against existing intruders who are determined to siphon off data on critical defense systems, political leanings, or data that will give favored firms an edge in the marketplace. In just one sign of the dire situation the U.S. finds itself in, the campaign networks of BOTH the Republican and Democratic candidates for president were hacked in 2008 by parties believed linked to foreign governments, with documents related to policy positions and other documents siphoned off.

This isn’t to say that the battle is lost. The U.S. has cyber offensive capabilities that enable it to give as good as it gets. Threatpost has been among a few outlets to editorialize that hyping the threat posed by China and other foreign nations can be counter productive, and also obscure our nation’s own cyber offensive capabilities. However, as we look about us for all the changes wrought by the cowardly and gruesome attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, we can find in the the remnants of attacks with names like “Shady Rat,” “Aurora,” “Byzantine Hades” and “RSA” one other sad legacy of Sept. 11 that, like so many others, doesn’t bode well for the future.