The FBI admitted on Monday morning that an attacker exploited a flaw in how an agency messaging system is configured: a flaw that let an unknown party send out a flood of fake “urgent” warnings about bogus cyberattacks.

The Spamhaus Project, a European nonprofit that monitors email spam, detected the exploit and tweeted about it early Saturday morning, saying that “We have been made aware of ‘scary’ emails sent in the last few hours that purport to come from the FBI/DHS. While the emails are indeed being sent from infrastructure that is owned by the FBI/DHS (the LEEP portal), our research shows that these emails *are* fake.”

We have been made aware of "scary" emails sent in the last few hours that purport to come from the FBI/DHS. While the emails are indeed being sent from infrastructure that is owned by the FBI/DHS (the LEEP portal), our research shows that these emails *are* fake.

— Spamhaus (@spamhaus) November 13, 2021

Late on Friday night, the FBI/DHS’s infrastructure – specifically, the Law Enforcement Enterprise Portal (LEEP) – had begun pumping out the alerts about fake cyberattacks, sent from the very real FBI address eims@ic.fbi.gov.

Around that time, that same email address reached out to security journalist Brian Krebs with this message:

“Hi its pompompurin. Check headers of this email it’s actually coming from FBI server. I am contacting you today because we located a botnet being hosted on your forehead, please take immediate action thanks.”

Pompompurin wasn’t lying. Analysis of the email’s message headers showed that the FBI’s email system did indeed send it, and from the agency’s own internet address. The email sender’s domain — eims[@]ic.fbi[.]gov — is that of the FBI’s Criminal Justice Information Services division (CJIS), Krebs confirmed.

Spamhaus said that the fake warning emails were sent to addresses scraped from the North American Registry for Internet Numbers (ARIN) database, and given that the headers were real, they caused “a lot of disruption.”

There were two gushes of mail, Spamhaus said, with a total of about 100,000 adrenaline-spiking messages that got out.

The following chart shows email traffic originating from the FBI mailserver (https://t.co/En06mMbR88 | 153.31.119.142) involved. You can clearly see the two spikes caused by the fake warning last night. Timestamps are in UTC. pic.twitter.com/vPKvzv74gW

— Spamhaus (@spamhaus) November 13, 2021

With no name or contact information in the signature, Spamhaus urged recipients to “Please beware!”

FBI Says Attacker Didn’t Get at Data or PII

“The FBI is aware of a software misconfiguration that temporarily allowed an actor to leverage the Law Enforcement Enterprise Portal (LEEP) to send fake emails,” the FBI’s statement said. The bureau describes LEEP as “a gateway providing law enforcement agencies, intelligence groups, and criminal justice entities access to beneficial resources.”

The FBI’s statement continued, explaining that “While the illegitimate email originated from an FBI operated server, that server was dedicated to pushing notifications for LEEP and was not part of the FBI’s corporate email service.”

The attacker wasn’t able to access or compromise any data or personally identifying information (PII) on the FBI’s network, according to its statement. “Once we learned of the incident, we quickly remediated the software vulnerability, warned partners to disregard the fake emails, and confirmed the integrity of our networks,” it said.

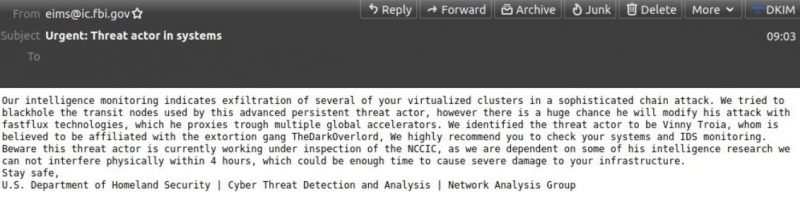

Bogus Alert Warning About Fake APT

According to the sender’s Twitter account description (and contradictory to their claims that the attack was done to point out a gaping security hole), pompompurin isn’t out to help anybody: “I AM NOT A WHITEHAT, don’t follow me if you expect those types of tweets.”

The purported attacker’s reference, in their conversation with Krebs, that foreheads can host botnets makes about as much sense as the fake alert itself. The warning was a string of technical gibberish that named cybersecurity writer Vinny Troia as well as a cybercriminal group called The Dark Overlord (one that Troia’s company, Night Lion Security, published research on in January).

The attacker signed off as the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Cyber Threat Detection and Analysis Group, which, as NBC reports, hasn’t existed for at least two years.

Fake alert from the FBI/DHS. Source: Spamhaus.

What’s the Point?

The fake alert had no call to action, making the goal of the fakery unclear. Spamhaus suggested – and this is just a guess – that it was “a combination scare-ware (get people to shut things down or make changes in a hurry), and a character assassination against the guy named in it, AND a way to make the FBI scramble.”

Triple action: Convince people to shut things down just in case, while veracity is determined, character assassination of Vinny Troia who was mentioned in it, and flooding the FBI with calls. Or, as someone else said, “for the lulz”. Maybe all of the above. Maybe something else! –Spamhaus

111612 17:38 UPDATE: Troia said, tongue in cheek, that he didn’t have a clue who’s behind the attack. He had a very good idea of who was behind it, having identified an alleged cybercriminal actor who, he said in a Tuesday post, has been tormenting him for a while.

But according to what the presumptive attacker – pompompurin – told Krebs, the point was to expose a gaping hole in the agency’s security setup.

Krebs quoted their email exchange: “I could’ve 1000% used this to send more legit looking emails, trick companies into handing over data etc. And this would’ve never been found by anyone who would responsibly disclose, due to the notice the feds have on their website.”

The Gaping Hole, Purportedly Explained

The purported attacker, pompompurin, explained to Krebs that the FBI’s system misconfiguration had to do with how LEEP allowed anyone to apply for an account. As Krebs noted, the instructions for how to do so included visiting the portal on an outdated browser: namely, Microsoft’s Internet Explorer, a browser that Microsoft itself, given the software’s security problems, would rather see pushing up the daisies than being used on a government website.

Part of the process includes applicants receiving an email confirmation from eims[@]ic.fbi[.]gov with a one-time passcode: a one-time password that the FBI’s own website leaked in the page’s HTML code, pompompurin told the journalist.

Krebs quoted the self-proclaimed attacker: “Basically, when you requested the confirmation code [it] was generated client-side, then sent to you via a POST Request,” pompompurin said. “This post request includes the parameters for the email subject and body content.”

The I’m-not-a-white-hat told the journalist that he used a simple script to replace the parameters with his own message subject and body, and automated the sending of the hoax message to thousands of email addresses.

A Noisy Attack That Could Have Done Real Hurt

Tim Erlin, vice president of strategy at Tripwire, lamented the fact that all it takes for an attacker to be able to send out a slew of bogus emails from a legitimate email address is a “simple modification of the traffic between a user and this web application.”

Exploiting the FBI’s infrastructure is an eye-popper, he told Threatpost via email on Monday, but the headline-grabbing, “noisy” attack could have done “significantly more damage,” Erlin said. “This incident highlights the importance of a secure software development program, web application testing, and security configuration management. This attack could have been stopped at multiple points in its lifecycle.”

111521 11:36 UPDATE: Added input from Tim Erlin.

Image courtesy of Shinsuke Ikegame, Daily Photos in Vancouver.

Cybersecurity for multi-cloud environments is notoriously challenging. OSquery and CloudQuery is a solid answer. Join Uptycs and Threatpost on Tues., Nov. 16 at 2 p.m. ET for “An Intro to OSquery and CloudQuery,” a LIVE, interactive conversation with Eric Kaiser, Uptycs’ senior security engineer, about how this open-source tool can help tame security across your organization’s entire campus.

Register NOW for the LIVE event and submit your questions ahead of time via the registration page.