SINT MAARTEN—Cybercriminals who used fileless, memory-based malware to carry out attacks on nearly 150 enterprises worldwide earlier this year were onto something.

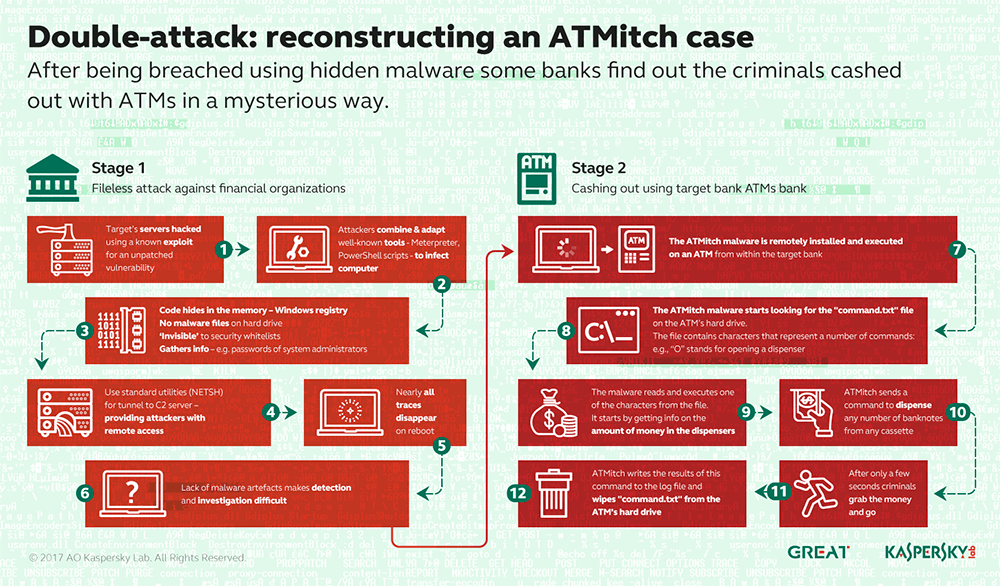

The attackers already had remote access to the bank’s networks through the malware, described in February, but once they were inside, they dropped another piece of malware called ATMitch on some bank ATMs that gave them the ability to dispense money, “at any time, at the touch of a button.”

Sergey Golovanov and Igor Soumenkov, principal security researchers at Kaspersky Lab, described the attacks in a talk here this afternoon at the company’s Security Analyst Summit. Attackers installed the malware on ATMs via the machine’s remote administration modules, something which gave them the ability to execute commands, such as tabulating the number of bills inside a machine or dispensing money.

Kaspersky Lab said in February that attackers managed to hit 140 enterprises, including banks, telecoms, and government organizations, with the fileless malware. The organizations were primarily in the U.S., U.K., and Ecuador but firms in Brazil, France, Tunisia, Turkey, Israel, and Spain – 40 countries overall – were also compromised. Today researchers described how the attackers used the malware to gain a firmer foothold into bank’s systems and cash out.

The researchers began researching the malware in earnest last summer after fielding requests from the bank asking them to asked to search through logs and carry out forensic research.

The attackers were skilled at evading detection from the get-go; the malware that secured them access to the banks hid deep in the recesses of memory on affected servers. After attackers make off with the funds, the malware simply deletes itself.

Golovanov and Soumenkov were able to analyze two files containing malware logs, kl.txt and logfile.txt, from an affected ATM’s hard drive. Forensics specialists at one of the banks that was hit by the malware shared the files. From there, researchers were able to find a sample for the malware by piecing together bits of information from the log files in clear text. They created a YARA rule for publicly available malware repositories, which yielded a sample.

YARA, a pattern-matching tool, is used by malware researchers to help identify and classify malware samples.

In this case the sample, “tv.dll” or “ATMitch” as the researchers began calling it, popped up twice in the wild – once from Kazakhstan, once from Russia.

Technically, once installed and executed via Remote Desktop Connection the malware looks for a file, command.txt. From there it reads characters inside the file which link back to different commands and executes them depending on the attackers’ needs. For example, “O” in this context stood for opening a money dispenser. ATMitch writes the results of the command to the log file and subsequently deletes command.txt from the machine’s hard drive.

The researchers aren’t entirely clear who’s behind the attacks but like they did in February, acknowledged that some of the group’s tactics, techniques, and procedures, or TTPs, bear a resemblance to methods used by the groups GCMAN and Carbanak. The malware used during the second stage of the attack, “tv.dll,” contains a Russian language resource, something which fits the profile of the groups as well.

The first stage of the attack, as described two months ago, relies on readily available open source utilities. Banks found Meterpreter, an extensible payload used by Metasploit on the remnants of memory on one domain controller. PowerShell scripts, Microsoft’s command-line scripting utility NETSH, and Mimikatz, a post-exploit utility, were also believed to have been used.

Since the malware is memory-based, it simply vanishes following a reboot. In some instances the attackers even use SDelete, a Windows command line utility that lets users delete files and directories, to cover their tracks.

Golovanov said Monday that the fileless malware attackers might still be active but that financial firms shouldn’t panic. Since so little information is actually left behind in these types of attacks, the researcher said memory forensics and a “carefully directed incident response” are critical steps to resolving breaches.

_______________

Golovanov and Soumenkov also described on Monday how they were able to reverse engineer another strain of ATM malware.

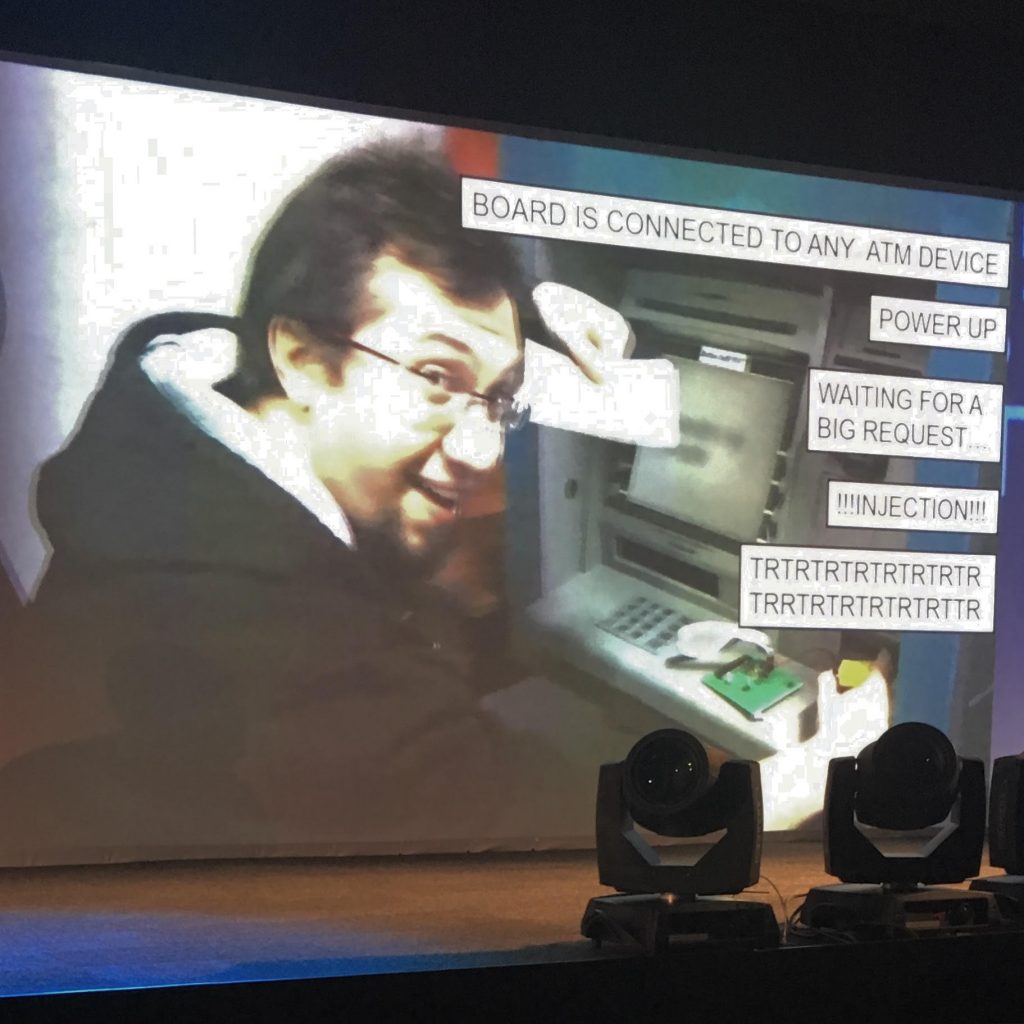

The researchers were tipped off about the hacks after a bank reported that a man dressed as a construction worker was drilling into an ATM near their office in the middle of the day. No one was concerned at first – then police came. The suspect was captured with hacking tools – cables, a laptop and a small box.

Golovanov and Soumenkov discovered that the suspect was injecting commands into a long wire that wends its way through ATMs. The wire, an SDC, or serial distributed control link, connects circuitry between devices like ATMs. The researchers had difficulty determining what was exactly was being transferred by the wire however; it was bulky and industrial but they had no idea what its port speed was, or really what protocol it ran. The duo was eventually able to determine the wire was RS485 standard and transferred encrypted 9-bit data.

Before long the pair were able to decode the protocol. They waited for a big request, replied and carried out an SDC bus stream injection in order to spit money out of the machine.

_______________

Golovanov, a member of the company’s Global Research & Analysis Team, described in 2015 at this conference how hackers from the Carbanak gang stole of $1 billion from financial institutions in a series of attacks.

Those attacks hit more than 30 IP addresses in 30 countries but mostly impacted the U.S. and Russia. Criminals leveraged a backdoor, which allowed them to install keyloggers to glean credentials. Some criminals hired money mules to collect money and transfer it over the SWIFT network, others got rich via ATM fraud.

At last year’s conference, Golovanov and another researcher, Vladislav Roskov, divulged details around two other bank-robbing gangs, Metel and GCMAN. Like the hackers behind ATMitch, both groups used legitimate pen-testing tools to carry out their capers. Metel used Mimikatz while GCMAN used VNC, a desktop sharing system, Putty, an open-source terminal emulator and file transfer app, and Meterpreter to move laterally in systems.

Researchers with the Israeli security company Morphisec said two weeks ago that it believed both the fileless malware campaign Kaspersky Lab uncovered and one unearthed by Cisco’s Talos researchers may be connected.

Researchers with the firm stumbled upon framework, now offline, in early March and said it was apparently used to launch a series of attacks designed to leave no artifacts behind on infected machines. It monitored a command and control server for three days and observed scripts that executed Mimikatz and a PowerShell script that opened a backdoor. While investigating a fileless malware attack at one of the banks Kaspersky Lab researchers discovered the use of PowerShell scripts within the Windows registry.