An update to Google Chrome’s sign-in mechanism could clear a path to compromising the privacy of users’ browser data, according to a researcher who stumbled across the change.

Matthew Green, a cryptographer and professor at Johns Hopkins University, noticed his Gmail profile pic strangely and suddenly appearing in his browser window—generally a sign that a user is logged in.

However, he hadn’t actually affirmatively signed in, which threw up a red flag. This led him to parse through Google’s last Chrome update (Chrome 69), where he discovered a significant change: That going forward, “every time you log into a Google property (for example, Gmail), Chrome will automatically sign the browser into your Google account for you.”

Previously, this log-in feature was opt-in only. Now, it’s automatic, and users don’t receive a notification that they’ve been signed in.

“The new feature that triggers this auto-login behavior is called ‘identity consistency between browser and cookie jar’ (HN),” noted Green, in a posting Sunday on the issue.

Privacy Concerns

On the surface this may seem trivial – the Google Chrome team said that being signed in does not mean that the browser will actually harvest and ship data to Google. A second step of giving active consent to the “sync” feature is required for that. But Green pointed out that there are reasons to be skeptical of this assurance.

“If you didn’t respect my lack of consent on the biggest user-facing privacy option in Chrome (and didn’t even notify me that you had stopped respecting it!) why should I trust any other consent option you give me?” Green said. He added, “I’m forced to…hope that the Chrome team keeps promises to keep all of my data local as the barriers between ‘signed in’ and not signed in’ are gradually eroded away.”

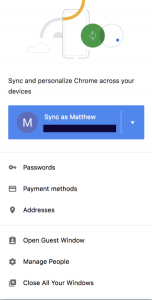

He also pointed out that navigating the “sync” feature (which, if turned on, would indeed allow Google to hoover up data) is far from intuitive, and could be easily turned on by a single accidental click—thus, it could confuse users into inadvertently giving consent for Google to harvest their data.

“The Chrome sync UI is a dark pattern. Now that I’m forced to log into Chrome, I’m faced with a brand-new menu I’ve never seen before,” he said. “Whether intentional or not, it has the effect of making it easy for people to activate sync without knowing it, or to think they’re already syncing and thus there’s no additional cost to increasing Google’s access to their data.”

There’s also a lack of clarity around how the sync feature works. Once the sync feature is turned on, it’s unclear if it just collects data from that point forward, or if it allows Google to access past data as well, Green pointed out.

Explanations

As far as Google’s stance on this, Green said that the explanations he received from the Chrome development team as to why the change was made are insufficient at best—in fact, he noted, they “don’t make any sense.”

The rationale he was given was that “if you’re in a situation where you’ve already signed into Chrome and your friend shares your computer, then you can wind up accidentally having your friend’s Google cookies get uploaded into your account. This seems bad, and sure, we want to avoid that.”

However, for that scenario to apply, a user would already have to be signed into Chrome. So, the explanation doesn’t actually address the question of why users must be logged into the browser.

“If signed-in users are your problem, why would you make a change that forces unsigned–in users to become signed-in?” Green noted.

This is the same territory that Adrienne Porter Felt from the Chrome team covered on Twitter Sunday night – although she provided a bit more clarity. She implied that rather than running the risk of inadvertent cookie-sharing on a shared device, the solution is just to force everyone to be signed in all the time.

“My teammates made this change to prevent surprises in a shared device scenario,” she tweeted. “In the past, people would sometimes sign out of the content area and think that meant they were no longer signed into Chrome, which could cause problems on a shared device.”

Google pointed Threatpost to Porter Felt’s Twitter thread in response to a request for comment.

Meanwhile, Chris Olson, CEO of The Media Trust, characterizes the move in a different way from Green: As being privacy-friendly.

“Google put this measure into place so that users of shared or publicly available devices and machines do not unknowingly share their information with other users,” he told Threatpost. “This measure is in keeping with GDPR’s requirement to obtain consumer consent before sharing their information with other parties.”

He added, “As data becomes increasingly regulated, companies will need to communicate, if not tout, their GDPR compliance efforts through easy-to-understand, continuously updated policies and through public announcements of new security and privacy features. Keeping consumers informed is an important step to gaining their trust.”

For those concerned with the auto-login feature and about potential privacy issues in Chrome, there is a work-around to the forced sign-in, available here.

From the standpoint of overall implications, Green said that he felt the situation represented a change in Google’s approach to users.

“Where Facebook will routinely change privacy settings and apologize later, Google has upheld clear privacy policies that it doesn’t routinely change,” Green said. “Sure, when it collects, it collects gobs of data, but in the cases where Google explicitly makes user security and privacy promises — it tends to keep them. This seems to be changing.”