MOSCOW — Attackers have been focusing a lot of attention on social networking destinations such as Facebook, Twitter and even LinkedIn for some time now, but they recently have begun shifting their tactics to make their attacks much more effective and precise through the use of geolocation and profiling.

MOSCOW — Attackers have been focusing a lot of attention on social networking destinations such as Facebook, Twitter and even LinkedIn for some time now, but they recently have begun shifting their tactics to make their attacks much more effective and precise through the use of geolocation and profiling.

Like attacks on other platforms such as email and IM, the first couple generations of attacks on social networking sites used a shotgun approach that relied on targeting a huge number of users and hoping that a small percentage of them would fall for the attack. The Koobface worm, Twitter spam and porn bots all relied on this tactic, and with pretty good results. Koobface’s various iterations have infected millions of Facebook users, and there have been a couple of fairly effective phishing campaigns on Twitter.

But users have been quick to catch on to those techniques, and attackers have begun to fine tune their tactics to make their attacks much more focused and effective, experts say. The most effective of these right now is the use of geolocation and profiling of users.

“We have really started to see a lot of attackers using geolocation for targeted attacks on social networking sites to better craft the social engineering story,” Stefan Tanase, senior regional researcher on Kasperky Lab’s Global Research & Analysis Team, said in a talk at the company’s international press briefings here. “They’re using language targeting and looking at profiles and interests to make it work.”

There has been a major increase in the volume of malware targeting social networking sites in the last year. As more and more users have flocked to Twitter and other such sites, the number of pieces of malware targeting these users has grown from fewer than 30,000 in 2008 to more than 60,000 in 2009, Tanase said.

The nature of sites such as Twitter and Facebook, where users post intimate details of their lives, including hobbies, job information, birthdays, etc., makes these attacks easy to implement. Attackers can sift through users’ profiles, looking for specific interests, information on where they live and what they do in their spare time. They can then use that data to target tailored phishing and drive-by attacks to a small group of users in a specific city.

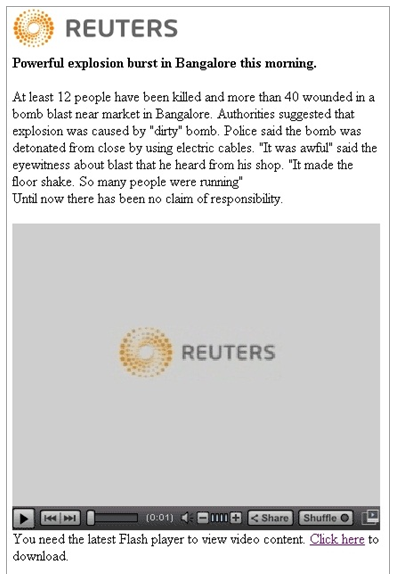

Tanase showed an example of a phishing campaign that used a fake Reuters site that had a news article purporting to be about a bomb blast in Bangalore. However, as users hit the site, if they came from other locations, the headline of the story could be changed to Moscow, Berlin, Chicago or whatever location matched the user’s IP address.

Advertisers have been using similar techniques to target their messages to local users on news sites, Facebook and elsewhere, and it’s turned out to be a very effective tactic. And if it works for legitimate advertisers, there’s no reason to think the attackers won’t see the same results, Tanase said.

“If the advertisers are doing it, and it’s working, there’s no reason the bad guys won’t,” he said. “They’re now automating the targeted attacks. That’s a dangerous thing. The complexity of these attacks will get bigger and bigger and the social engineering attacks are getting more complicated.”