There have been some strides made in the last year, but for the most part, security around the healthcare industry has remained the consummate laggard.

In the eyes of many, including Scott Erven, a medical device security advocate who spoke at last week’s Security Analyst Summit, the healthcare sector is a good 10 to 15 years behind the retail sector when it comes to security.

It’s going to come to a breaking point sooner or later, he warned.

“We have got to get better on this going forward,” said Erven, who’s also an associate director at the consulting firm Protiviti.

Erven, who focuses on medical device security and spent 15 years as a security researcher, knows just how broken the system is. He’s seen it all – weak, hard-coded credentials, woefully out of date, legacy devices running XP and NT.

A few years ago he worked with fellow healthcare researcher Shawn Merdinger and discovered that hundreds of hospitals, clinics, and health centers connected to a large US healthcare system, which contained over 12,000 employees and 3,000 physicians, were vulnerable.

The two did a Shodan search for anesthesia and located a slew of public systems with Server Message Block (SMB) open, meaning they were leaking intelligence, host names, and other identifiable information about networks at the organizations.

A variety of devices were vulnerable, including cardiology systems, infusion systems, MRI machines, and nuclear medicine systems, Erven said. The two discovered 30 CVEs in total — many which involved MS08-067, an old remote code execution hole from 2008 that implicated Server service, and could allow an attacker to easily pivot into a network. This was the vulnerability exploited by the Conficker worm.

“Prior to devices entering the market, there’s no validation of security controls,” Erven said, visibly upset with the state of the system, “Every sociopath on the internet is your next door neighbor.”

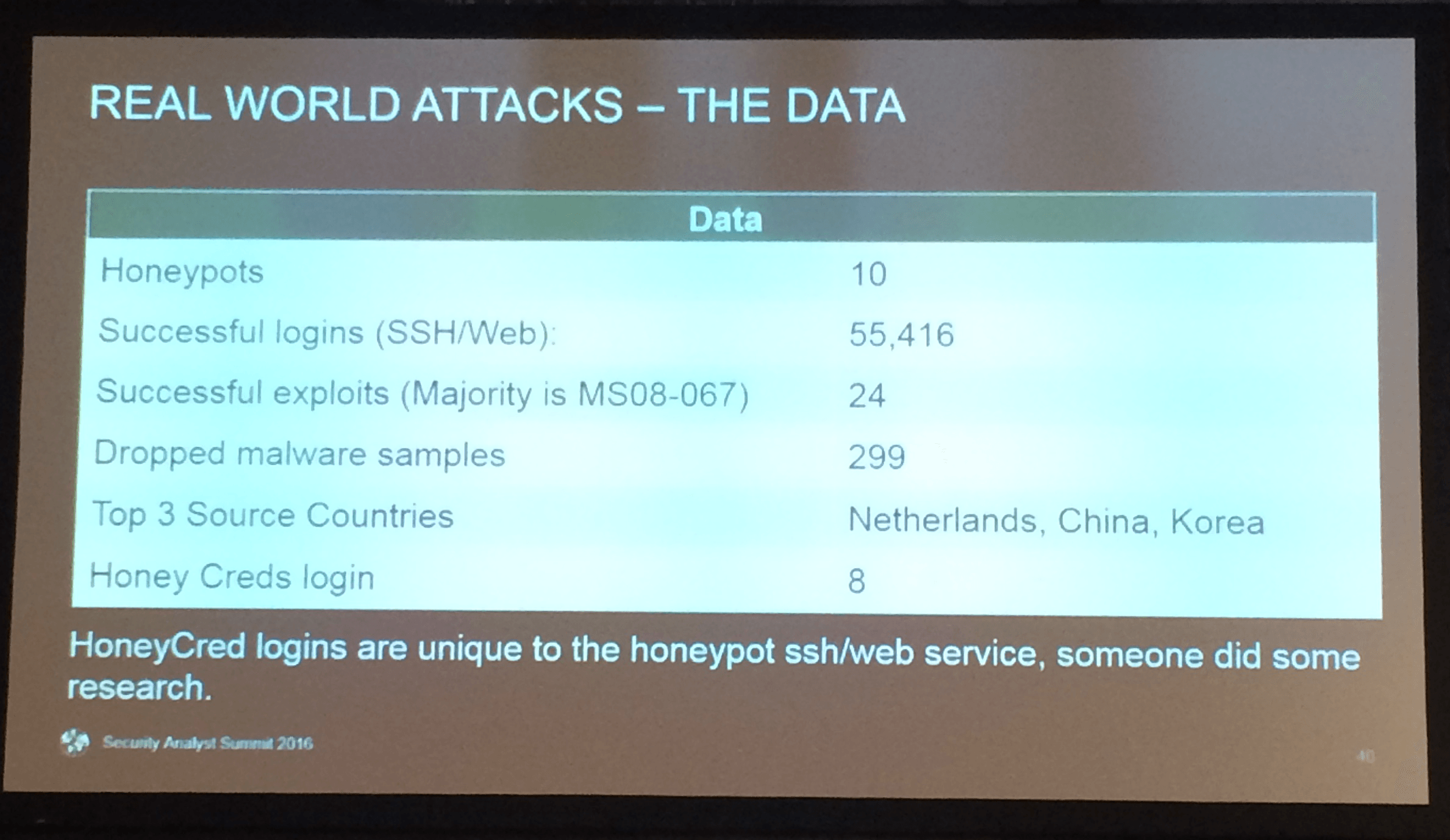

Looking to take it a step further and learn more about what exactly what kind of attacks were being carried out on medical devices, Erven said he built a series of 10 honeypots recently, each designed to mimic a different device.

The result? Erven saw 299 samples of malware dropped, much of it originating from the Netherlands, China, and Korea. He also noticed a staggering number of successful SSH/web logins: 55,416. Erven documented 24 successful exploits overall, the majority which using MS08-067.

Erven even published a handful of honeypot credentials (HoneyCreds) on Pastebin and noticed eight instances where someone tried to use them to login, signaling that attackers were actively doing research to get into his systems.

For all of the industry’s plight, Erven highlighted some advances in the past year.

The IEEE Cybersecurity Initiative published a building code for securing medical devices last May to give companies a foundation when it comes to developing and producing software.

Similarly the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued premarket guidance to medical device manufacturers in 2014 and followed it up with postmarket guidance, clarifying how the security of devices should be addressed after they’ve been given the green light to go to market, last month.

When the Food and Drug Administration warned last summer that hospitals should stop using a pump manufactured by Hospira, Erven said it was precedent setting. The move came largely thanks to research carried out by Billy Rios which identified flaws in the pump’s software and was the first time a safety notification was issued because it could lead to the loss of a life.

Erven empathized multiple times during his talk that malicious intent isn’t a prerequisite for patient safety issues, especially when it comes to some of the more far-flung vulnerabilities in medical devices. As it stands now, there’s very little, if any validation of security controls prior to devices entering the market, he argued.

While we may lack forensically sound evidence linking attackers with malware loaded onto pumps, it shouldn’t keep us from securing them, he rationalized.

“We can’t accept what we have now,” Erven said. “If we assume a loss of life scenario, the consequence of failure is too high.”