Wireless keyboards made by eight different companies suffer from a vulnerability that can allow attackers to eavesdrop on keystrokes from up to 250 feet away, researchers warned Tuesday.

If exploited, the vulnerability, dubbed KeySniffer, could let an attacker glean passwords, credit card numbers, security questions and answers – essentially anything typed on a keyboard, in clear text.

Keyboards manufactured by Hewlett-Packard, Toshiba, Kensington, Insignia, Radio Shack, Anker, General Electric, and EagleTec are affected, according to Marc Newlin, a researcher with Bastille Networks that discovered the vulnerability.

Newlin began to look into the security of wireless, non-Bluetooth keyboards shortly after Bastille disclosed research around Mousejack, a similar vulnerability he discovered in February that allows attackers to inject keystrokes into wireless mice.

After purchasing wireless keyboards from a big box store, Newlin’s plan was to reverse engineer the devices, figure out their protocols and start looking for problems with their encryption.

It turned out that eight of the 12 they tested – two thirds – didn’t have encryption to begin with.

“As soon as I had finished the initial reverse engineering process it was immediately clear that these devices were sending all the keystrokes in clear text,” Newlin told Threatpost this week.

Newlin claims the devices have three transceivers that were not previously documented. Keyboards from Hewlett-Packard, Anker, Kensington, RadioShack, Insignia, and EagleTec use transceivers from MOSART Semiconductor, while keyboards from Toshiba use transceivers from Signia Technologies. The keyboard from General Electric used an “entirely unknown” transceiver.

Transceivers usually feature a combination transmitter/receiver but in the eight keyboards, there was basically no information on what the chips on the devices were, or how they worked. The undocumented transceivers forced Newlin and the rest of the Bastille Research Team to reverse engineer the physical layer and radio frequency packet formats before the data could be examined.

All of the keyboards are currently sold in stores, Newlin stressed. While some of the devices were designed years ago and have been on the market for some time, some were introduced as recently as 2014 or 2015.

“We would have expected that more vendors would have started considering security more closely but unfortunately it seems like many of them haven’t,” Newlin said.

Similar to the Mousejack vulnerability, an attacker could purchase some fairly inexpensive radio equipment off of Amazon – Crazyradio a long range 2.4 GHz radio USB dongle that usually costs $30 to $40 – in order to eavesdrop on victims.

After he reverse engineered the transceivers, Newlin was able to write firmware for another transceiver, the one in the Crazyradio dongle, that could make it behave like a dongle from the keyboards. Using that, coupled with a $50 directional antenna, just under $100 in equipment, he could sniff data from around 250 feet as well as inject keystrokes into the keyboard’s USB dongle.

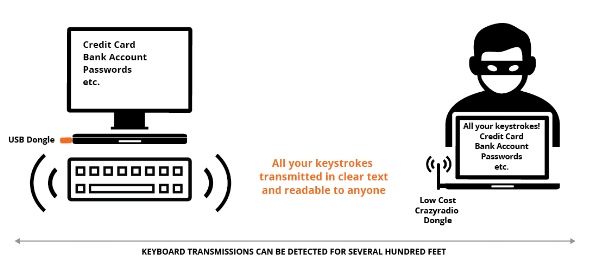

How KeySniffer works

User types on their keyboard, with unencrypted data being transmitted wirelessly to the USB dongle plugged into their computer. An attacker is in range with a laptop and USB dongle, and also receives the same unencrypted keystrokes. (via keysniffer.net)

Unlike the Mousejack vulnerability, in which the user had to be actively using their mouse or typing on their keyboard in order to be identified, the keyboards’ USB dongles are constantly transmitting radio packets that allow the keyboards to find the dongles.

“Even if the user is not at their computer or typing on their keyboard the USB dongle is constantly transmitting data wirelessly,” Newlin said, “that makes it easy for an attacker to survey a building, room or area and quickly identify all these keyboards that are vulnerable to this type of attack.”

Bastille gave the manufacturers of the keyboards 90 days to address the vulnerability, but most vendors failed to respond to their findings. Newlin claims that only Jasco Products, a company that manufactures the affected keyboard (GE 98614) for General Electric, responded and claimed it no longer manufactures wireless devices, like keyboards.

As there doesn’t appear to be a way to actually fix the vulnerability, it’s likely the companies will eventually consider the devices end of life.

“As far as I’m aware there’s no way to update the firmware on these devices because they have the functionality that defines the keyboard logic kind of baked into the chip on the device. There’s no room, or at least minimal room for vendor customization,” Newlin said, “To my knowledge, there’s no way they can simply turn on encryption or anything to that effect.”

Bastille is encouraging anyone using one of the vulnerable keyboards to unplug it and switch to a wired or Bluetooth enabled keyboard. While Bluetooth isn’t the most secure protocol, it’s demonstrably more secure than those used in the eight keyboards.

Both wireless keyboards and Bluetooth usually follow proprietary protocols that run in the 2.4GHz ISM band and can be subject to interference from other devices operating in that same band.

Noted hardware hacker and security researcher Samy Kamkar found a way last year to passively sniff, decrypt, and record keystrokes entered on Microsoft wireless keyboards. By piecing together an Arduino controller and other assorted electronic bits, Kamkar created a device, KeySweeper, that looks like a USB wall charger but could easily be used for surveillance. The FBI issued a warning around the tool in April but wouldn’t go on record that attacks were being carried out in the wild.

While KeySweeper exploited a specific weakness in Microsoft’s encryption, Newlin’s KeySniffer research is scarier, because it’s tied to the lack of encryption entirely.

“It’s not even a matter of weak encryption, it’s simply a complete lack of encryption,” Newlin told Threatpost Monday.

Also, unlike KeySweeper, which really only had the range of a Bluetooth device, any attack that leverages the KeySniffer vulnerability could be carried out on a much larger scope. Home users in apartment complexes, employees at office parks; anywhere that wireless keyboards are clustered together could be a ripe target, Bastille warned.

Newlin, who’s scheduled to discuss both KeySniffer and Mousejack at next weekend’s DEF CON convention in Las Vegas, was able to amplify the attack range for Mousejack in April. By applying better antennas he was able to up the range to 225 meters, up from 100 meters. As part of the original Mousejack research, Newlin discovered he could send packets to wireless mice or keyboards that generate keystrokes, instead of mouse clicks, as an avenue to installing malware and rootkits on a victim’s machine.

There is no such thing as too many dongles. #mousejack #defcon pic.twitter.com/ghMW8SJs8M

— Marc Newlin (@marcnewlin) July 21, 2016

Many of the up and coming protocols associated with IoT are still in their infancy. That combined with the lack of industry wide support and unresolved IoT standards have made it an uphill battle for anyone trying to secure IoT specific-devices.

Vulnerabilities were identified in Comcast’s Xfinity Home Security System, which runs on the ZigBee wireless communication protocol, earlier this year that could interfere with its ability to detect and alert to home intrusions. Last year a researcher identified that Z-Way, a layer that feeds into Z-Wave, another standard for wireless communication between devices in smart homes, lacks authentication by default.