Attackers have rekindled their love affair with Windows macros over the last few years, using the series of automated Office commands as an attack vector to spread malware. And while hackers will surely continue to use macros, at least until the technique becomes ineffective, new research suggests they may be shifting gears and beginning to use another proprietary Microsoft technology to deliver threats.

Attackers have been placing malicious code alongside object linking and embedding (OLE) code, along with well-formatted text and images. According to researchers with Microsoft who observed the behavior, it’s being done to trick users into enabling the object or content and in turn, running the malicious code.

OLE technology allows for the facilitation of content, images, text, from elsewhere, usually by another application. If a user wants to edit the embedded data they can allow Windows to activate the originating application and load the content.

In many cases a script or object prompts users to interact with it. If the user is duped into enabling a malicious object or clicking on it, the code will run and an infection could occur.

Microsoft Malware Protection Center’s Alden Pornasdoro claims researchers there came across a rigged Word document just last month that used both Visual Basic script and JavaScript to levy an attack.

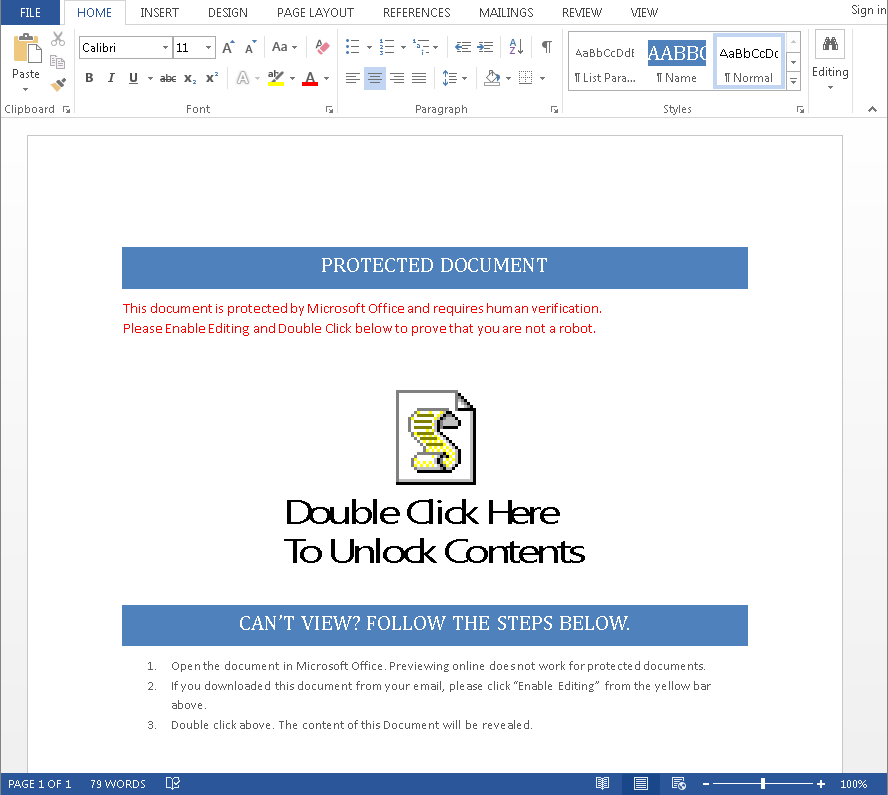

To boot the documents came with prompts that encouraged users to open the file. The wording, “Double click below to prove that you are not a robot,” sounds like a document attempting to verify a human is opening it.

Microsoft points out that similar to macros, education can be key when it comes to users mitigating attacks. If a user doesn’t click on the link or enable the content they could save themselves a lot of trouble in short order.

“It’s important to note that user interaction and consent is still required to execute the malicious payload,” Pornasdoro wrote, “If the user doesn’t enable the object or click on the object – then the code will not run and an infection will not occur.”

“As with spam emails, suspicious websites, and unverified apps. Don’t click the link, enable the content, or run the program unless you absolutely trust it and can verify its source.”

Pornasdoro claims that if a user did click through and run the script in the document they looked at it would download a binary that could bypass protection and ultimately go on to drop a version of the Cerber ransomware on victims.

Using OLE technology to carry out attacks isn’t particularly new; the company previously patched vulnerabilities, including a nasty zero day in 2014 which allowed remote attackers to execute code via specially crafted OLE objects. It wouldn’t be a surprise if attackers were looking to shake things up however, especially given the success they’ve had pushing banking Trojans and bots with macros of late.

Officials at Microsoft first started seeing an uptick in macros-based threats more than a year ago and despite being a fairly archaic attack vector, it’s managed to work for attackers. To show exactly just how what’s old is new again, in May researchers at the company described how attackers have been able to take things to the next level and store commands inside the name of a macro button to elude detection.

The company stresses that in addition to education, users can help prevent both macros and OLE-triggered attacks through settings in Office. Users can prevent OLE package activation by modifying the registry key in Office 2007-2016 and similarly, a new macro blocking feature in Office 2016, Group Policy Management Console, can allow admins to isolate macro use to a set of trusted workflows.