The Lyceum threat group has resurfaced, this time with a weird variant of a remote-access trojan (RAT) that doesn’t have a way to talk to a command-and-control (C2) server and might instead be a new way to proxy traffic between internal network clusters.

Kaspersky’s Mark Lechtik – senior security researcher at the company’s Global Research & Analysis Team (GReAT) – said in a Monday post that the team has identified a new cluster of Lyceum activity that’s focused on two entities in Tunisia.

In a paper (PDF) presented earlier this month at the Virus Bulletin conference, Lechtik and fellow Kaspersky researchers Aseel Kayal and Paul Rascagneres wrote that the threat actor has attacked high-profile Tunisian organizations, such as telecoms or aviation companies.

That fits into the group’s target list. Lyceum has been active since as early as April 2018, when it attacked telecoms, and critical infrastructure in Middle Eastern oil-and-gas organizations. Lyceum treads lightly but carries a big stick: “All the while it has kept a low profile, drawing little attention from security researchers,” the trio of researchers wrote.

The Lyceum group (aka Hexane) was first exposed in 2019 by Secureworks, which spotted the group targeting Middle Eastern energy firms and telecoms with malware-laced spearphishing emails.

Back then, Lyceum was using various PowerShell scripts and a novel .NET-based remote-access trojan (RAT) called DanBot, which deployed post-intrusion tools to spread across infected companies’ networks, steal credentials and other account information, and log keystrokes. DanBot communicated with a C2 server via custom-designed protocols over DNS or HTTP.

Kaspersky’s new Lyceum findings were sparked by a PowerShell script (MD5: 94eac052ea0a196a4600e4ef6bec9de2) that was submitted to VirusTotal in last November, and which helped researchers to follow the threat group’s more recent tracks.

“The script is obfuscated and Base64-encoded, suggesting that it was perhaps trying to evade detection in a victim’s environment,” according to the paper. “But after de-obfuscating it, the resulting code shows many comments that were left by the attackers, detailing what the script does and even explaining the changes from previous versions. Some of the functions were also marked as obsolete, suggesting that this script is possibly a work in progress.”

While it’s kept relatively quiet, Lyceum hasn’t been silent. In fact, Kaspersky has found enough threads to tie it back to the APT34/OilRig threat actor, as detailed below.

Off of .NET, Onto C++

The group’s tracks show that Lyceum’s arsenal has evolved. The group has shifted from its earlier .NET malware and onto new versions written in C++. Kaspersky has defined two clusters of variants, named “James” and “Kevin” simply because those were the names on the systems used to compile the malware.

Those DanBot variants cropped up a few months after Secureworks published its findings about Lyceum, suggesting that the publicity put some hurt on the group, as Kayal noted during the Virus Bulletin conference:

“There is a time gap of a couple of months between the previously documented DanBot and the two newer variants,” she said. “We believe that this is probably due to SecureWorks’ publication, and that the attackers might have decided to introduce some changes to their toolset after some of them were exposed in this report.”

Both of the new DanBot variants, like the original DanBot, support similar custom C2 protocols tunneled over DNS or HTTP, Lechtik explained in his Monday brief. “That said, we also identified an unusual variant that did not contain any mechanism for network communication,” he said. “We assume that it was used as a means to proxy traffic between two internal network clusters.”

Kevin, You Weirdo

Kaspersky thinks that the Kevin variant may “represent a new branch of development in the group’s arsenal,” according to the paper.

The variant first appeared in June 2020, with most samples carrying a string signifying that it was an internal version named v1.0.2. Then, 10 months ago, in December, a new wave of samples from the Kevin variant emerged, carrying the version number v2.1.0.2.

The variant introduced changes in communication protocols and is mostly compiled for 64-bit systems. Its purpose is “to facilitate a communication channel that passes arbitrary commands to be executed by the implant,” according to Kaspersky’s writeup.

“To do this, the malware requests files that will be created in the file system and written with commands received from the server using a specified format,” the paper continued. “The contents of the file will be read and interpreted by the implant according to that format, where predefined keywords will be replaced with certain malware-related paths or used to update internal run-time configurations. In turn, the commands will be executed, issuing the response back to the server.”

But before communication happens, the Kevin variant may bootstrap and prepare the victim environment for its execution through a set of actions common to a lot of its samples, as researchers described.

A partial list of those actions:

- Hides the current window from the user using the ‘ShowWindow’ API function.

- Creates a mutex with a lower-case GUID value that is hard coded in the binary.

- Checks the arguments with which it was executed. It’s mandatory that the first argument is equal to a version number (e.g., v1.0.2 or v2.1.0.2). “We assess that this could have been incorporated in order to avoid full execution of the malware functionality in sandboxed environments,” the researchers explained.

Tracing the Threads to Other APTs

Kaspersky researchers said that they noticed certain similarities between Lyceum and the infamous state-sponsored campaign from the DNSpionage group, which scooped up credentials by targeting national security organizations across the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) – and elsewhere – with domain name system (DNS) hijacking attacks.

DNSpionage is in turn associated with APT34/OilRig, Lechtik said in his Monday writeup: An advanced persistent threat (APT) that launched a series of cyberattacks on a Middle Eastern telecom in July 2020.

“Besides similar geographical target choices, and the use of DNS or fake websites to tunnel C2 data as a TTP [tactics, techniques and procedures), we were able to trace significant similarities between lure documents delivered by Lyceum in the past and those used by DNSpionage,” he wrote. “These were made evident through a common code structure and choices of variable names.”

The researchers noted that Lyceum’s modus operandi “bears a striking resemblance to that of APT34/OilRig.”

According to the paper, “Both groups have similar geopolitical targeting, and prefer to use DNS tunneling in the different payloads they have developed over the years. Although we did not find conclusive evidence to support this, we did notice some similarities between the delivery documents used by Lyceum back in 2018-2019 and those by DNSpionage, which is also believed to have ties to OilRig.”

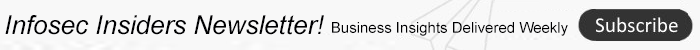

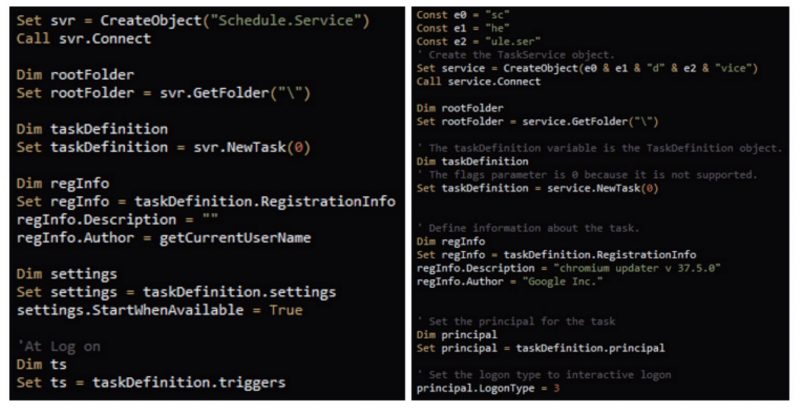

As well, the macros embedded in documents from the two groups share the same variable names and a similar code structure, as shown below.

Attacks Started with Excel Docs

When Lyceum/Hexane was first exposed, its attacks were started with Excel documents boobytrapped with malicious macros. One of the observed attacks used messages promising to display a list of events related to industrial control systems or to Middle Eastern gas-and-oil content. Another malicious spreadsheet pretended to be related to security, purporting to contain a list of the worst passwords since 2017.

In its recent investigation, Kaspersky identified some of Lyceum’s other MOs, including some of the commands the attackers used within the compromised environments, as well as how user credentials stored in browsers were stolen by using a PowerShell script, and details about a custom keylogger deployed on some of the targeted machines.

Kaspersky’s paper takes a deep dive into the technical aspects of its investigation into Lyceum, but the TL;DR version is that the APT didn’t blink out of existence following its discovery in 2019, and we’ll likely hear more about it still.

“With considerable revelations on the activity of DNSpionage in 2018, as well as further data points that shed light on an apparent relationship with APT34, we can assess that the latter may have changed some of its modus operandi and organizational structure, manifesting into new operational entities, tools and campaigns,” according to Kaspersky’s paper.

Lyceum=Outgrowth of DNSpionage?

One of the new operational arms of DNSpionage is, in fact, Lyceum, Kaspersky asserted. “After further exposure by Secureworks in 2019, [Lyceum] had to retool yet another time,” leading to the campaign Kaspersky described in its paper.

Lyceum hasn’t ceased operation; rather, the group has “attempted to gain a foothold on the targeted networks time and time again,” the researchers said.

The APT has not only kept up its attempted attacks through 2021. And, its samples also show code variations that point to the group having started to retool once again.

“With the exposure of this publication, we assess that Lyceum will continue to be active, using renewed malware and TTPs and adjusting its capabilities to conduct espionage and counterintelligence operations in the Middle East,” the researchers predicted.

Check out our free upcoming live and on-demand online town halls – unique, dynamic discussions with cybersecurity experts and the Threatpost community.