LAS VEGAS—The FruitFly backdoor became a known entity in January, but it’s a good bet that for years it had been in the wild, undetected by analysts and security software.

The macOS and OS X malware has a number of insidious spying capabilities that would make anyone uneasy, and a variant recently analyzed by Synack chief security researcher Patrick Wardle was no exception.

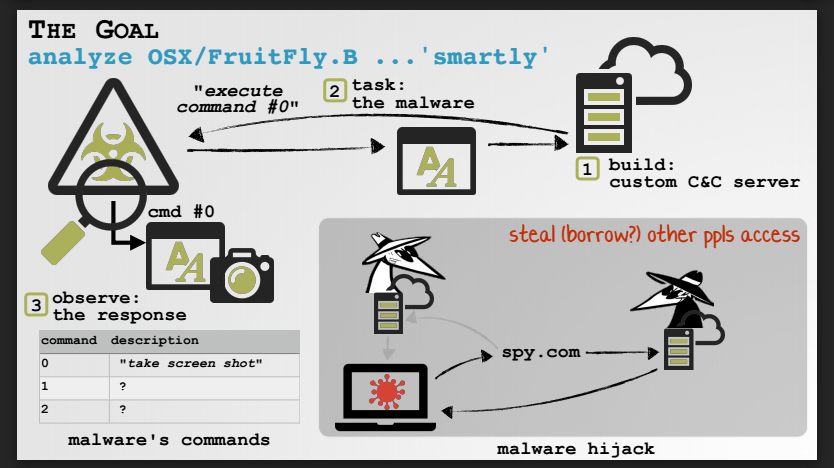

Wardle built a custom command and control server to examine a FruitFly sample that was capable of executing shell commands, retrieving screen captures, manipulating mouse movements, killing processes and even triggering an alert to the attacker when the user is active again on their Mac.

Wardle is expected on Wednesday during a talk at Black Hat to delve deeper into his analysis of FruitFly and the custom C&C server he used. He’s also said he will release a number of tools used in his analysis, including a user-mode process monitor.

“[FruitFly] was designed in a way to be interactive,” said Wardle, a former NSA analyst and founder of Objective-See where he has published a number of free tools for Mac malware analysis. “This can move the mouse, generate presses and interact with the UI elements of the operating system.”

The victims, meanwhile, are anomaly in that they’re “normal, everyday users,” as characterized by Wardle, who during his analysis was able to register a number of backup command servers included in the code and learn valuable victim information that he shared with law enforcement, along with the C&C servers he registered.

Unlike other spyware samples—including the FruitFly sample disclosed earlier this year by Malwarebytes—this variant did not appear to target researchers, high-profile organizations or defense contractors. In fact, most of the victims are in the United States, including a noteworthy concentration of them in Ohio.

“The computer names look like they belong to normal, everyday people. That leaves someone using this malware to surveil people,” Wardle said.

Malwarebytes’ Thomas Reed said in January that the sample he’d analyzed had been in the wild for some time and was targeting biomedical research centers.

Wardle, meanwhile, took a bit of an unorthodox approach in studying the FruitFly sample he had access to by building his own command and control server. This simplified analysis, he said, given that he was in possession of a sample. Rather than having to unpack and reverse-engineer the malware, he just set it loose in a test environment on a virtual machine replete with instrumentation tools. That server connected to a development machine on the test network where Wardle tasked the malware to execute and observed what was going on.

“It’s not an Earth-shattering technique; I’m sure it’s something others have done,” Wardle said. “To be able to analyze it, you have to understand the malware’s protocol. This one is straightforward and easy to parse, no custom encryption.”

The malware did also contain a number of encrypted connections to the backup command and control servers that were available in case the primary C&Cs went offline.

Once Wardle discovered that the backup servers were available, he registered them. Immediately, he said, victims (about 400, which is likely a small subset of a larger pool of victims) began connecting to the domains and sending system information such as user and computer names and IP addresses, none of which he interacted with, Wardle said, and instead turned over to law enforcement.

As for the malware’s behavior, Wardle said as he triaged the sample, he saw a laundry list of simple commands and sub-commands; for example, the No. 2 would take a screen capture, while the No. 8 would initiate a mouse action, with the No. 1 sub-command, for example, initiating a left-click.

“In the lab, I could modify host files to give it my box’s IP address and I knew I could get it to call out to me,” Wardle explained, adding that he could also provide an IP address and port via the command line to the malware, making it easier to get the malware to call out to his command and control server.

“When [the malware] connects, it gets a chunk of system data and then expects you to send back a command to execute,” Wardle said. “I triaged the language the malware expected it to speak and then created a Python script that responded in a way the malware expected.”

Wardle said there are tools, some of which he’s developed such as BlockBlock for detecting persistence mechanisms and OverSight for detecting webcam alerts, that would have lessened the risks to users. He added the initial infection vector is unknown, but he did conclude that given the relatively small number of known victims, it’s likely that one person is managing this operation and its size is what kept it under the radar.

“It’s likely a single entity controlling these victims,” Wardle said. “For a one-person operation, this would be what you would expect.”