Mamba was among the first samples of ransomware that encrypted hard drives rather than files that was detected in public attacks, primarily against organizations in Brazil and in a high-profile incursion against the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency last November.

Researchers at Kaspersky Lab said today in a report that a new run of Mamba infections have been spotted again in Brazil and Saudi Arabia.

The malware is the latest sample extending a trend of attackers disguising sabotage within a ransomware attack, which began with Petya and Mischa in early 2016 and peaked this year with the ExPetr/NotPetya wiper malware attacks. It’s unknown who is behind the most recent Mamba attacks, whether it’s a nation-state or a criminal enterprise.

In a talk yesterday, Kaspersky Lab researchers Juan Andres Guerrero Saade and Brian Bartholomew predicted this trend would continue and speculated that for now attacks disguised as ransomware for the purpose of sabotage remain within the realm of APTs.

“Let’s say we have all the means for a sabotage attack and we want to disguise it as ransomware or as something potentially treatable, it’s not necessarily that different from what the Lazarus Group did with Sony, or some other South Korean targets, where first they asked for money and then dumped data anyways. It’s an evolution that’s particularly troubling,” Guerrero-Saade said.

Unlike the ExPetr attacks where it was unlikely victims would be able to recover their machines, that may not be the case with Mamba.

“Authors of wiper malware are not able to decrypt victims’ machines. For example, if you remember the ExPetr [malware], it uses a randomly generated key to encrypt a victim machine, but the trojan doesn’t save the key for further decryption,” said Kaspersky Lab researcher Orkhan Memedov. “So, we have a reason to call it ‘a wiper.’ However, in case of Mamba the key should be passed to the trojan as a command line argument, it means that the criminal knows this key and, in theory, the criminal is able to decrypt the machine.”

Mamba appeared in September 2016 when researchers at Morphus Labs said the malware was detected on machines belonging to a energy company in Brazil with subsidiaries in the United States and India. Once the malware infects a Windows machine it overwrites the existing Master Boot Record, with a custom MBR and encrypts the hard drive using an open source full disk encryption utility called DiskCryptor.

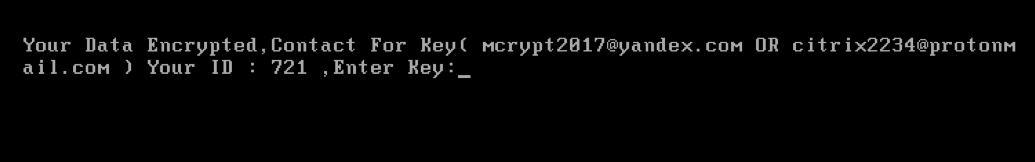

A ransom note, published (see below) by Kaspersky Lab, shows no demands for money unlike the original Mamba infections. Instead, it just claims data has been encrypted and provides two email addresses and an ID number in order to recover the encryption key.

“Unfortunately there is no way to decrypt data that has been encrypted with the DiskCryptor utility, because this legitimate utility uses strong encryption algorithms,” Kaspersky Lab said in its report.

The report suggests also that the group behind the latest Mamba attacks in Brazil and Saudi Arabia uses the PSEXEC utility to execute the malware on the corporate network once it has a foothold. PSEXEC was at the heart of the ExPetr malware attacks, which shared a number of similarities to the Petya attacks. ExPetr used PSEXEC and WMIC, another Windows utility, spread on local networks. Its goal was not profit, but destruction; analysts looking at the malware quickly the determined the ransomware functionality was faulty and victims would never be able to recover their files. The true purpose of those attacks was to wipe out the hard drive.

According to today’s report from Kaspersky Lab, attacks are happening in two stages. During the first stage, DiskCryptor is dropped into a new folder created by the malware and installed. A system service called DefragmentService is registered for persistence, and the victim’s machine is rebooted.

The second stage sets up the new bootloader and encrypts disk partitions using DiskCryptor before the machine is rebooted again.

“It is important to mention that for each machine in a victim’s network, the threat actor generates a password for the DiskCryptor utility,” Kaspersky Lab said in its report. “This password is passed via command line arguments to the ransomware dropper.”