Drones, many readily available on ecommerce shops such as Amazon, are plagued by vulnerabilities that could give attackers full root access to the device, read or delete files, or crash the device.

The United States Computer Emergency Readiness Team (US-CERT) published a warning about one model, the DBPOWER U818A WiFi quadcopter, last month, but according to the researcher who reported the vulnerabilities, multiple drone models– manufactured by the same company but sold under different names – are also vulnerable.

Junia Valente, a Ph.D. candidate in software engineering at the University of Texas Dallas, discovered the bugs last fall through UT’s Cyber-Physical Systems Security Lab, a program in the school’s computer science department that provides students IoT devices.

Valente’s research, carried out under the supervision of Dr. Álvaro Cárdenas, has been mostly focused on the security of these devices. The researcher is currently in discussions with a smart toy manufacturer to fix a vulnerability that could allow an attacker to eavesdrop on communications of a child from the internet and inject the attacker’s voice into a smart toy. In February, US-CERT warned of vulnerabilities – a hardcoded password and an authentication bypass – Valente found in surveillance systems manufactured by Swann.

The issue with drones, Valente says, is two-pronged. They contain two appealing attack vectors: an open access point and a misconfigured FTP server. If an attacker was within WiFi range of the drone they could easily obtain read and write permissions to the drone’s filesystem and modify its root password, Valente told Threatpost last week.

Valente discovered she could overwrite the drone’s remote password file after identifying inconsistencies with its permissions. A malicious user could run a command, such as “curl -T shadow ftp://192.168.0.1:21/etc/jffs2/shadow to overwrite the file with a ‘locally-crafted ‘shadow’ file with the entry ‘root::0:0:99999:7:::’ for the root user,” she told Threatpost.

In one instance she found that by overwriting the password, an attacker could remotely log in to the device through Telnet. A user would see a login prompt but would only have to type “root” for the user name and press enter to get in–no password required.

Like any attack dependent on Wi-Fi, an attacker would need to be in close proximity to the drone to carry out an attack, Valente claims, but reasons that an attacker could connect their computer to the drone access point, essentially treating it as a proxy to spy on the device’s live feed or the drone’s open ports.

“One experiment I tested was to connect my laptop to the drone access point and share that connection to other devices. In this setup, multiple devices were able to have access to the drone and the drone’s open ports,” Valente said,

“The scenarios are limited by an attacker’s creativity,” Valente told Threatpost.

Once in, an attacker could see what programs are running inside the drone, what devices are connected to its access point, survey any active network connections, power it off–as demonstrated in the video below–or block network traffic to disrupt a user’s viewing experience.

An attacker could also see or download any videos or photos on the drone and delete files on its SD card, Valente said.

The fact the U818A device runs version 1.20.2 of BusyBox, released in 2012 doesn’t help either. BusyBox, a collection of Unix utilities that works as a single binary commonly found in embeddable devices, has a host of known vulnerabilities. Valente says in some instances it could be possible to exploit some of them by sending a command to power off the device, something that would take it down mid-air. Attackers could also DDoS the drone, essentially bricking the device, and freeze the video stream from the drone to the drone’s app by blocking network packets.

US-CERT reached out to DBPOWER, a British company that also makes portable LED projectors, IP cameras, and portable car jump starters, about the vulnerabilities. After failing to hear back after 45 days, the group published a Vulnerability Note, acknowledging Valente for her findings.

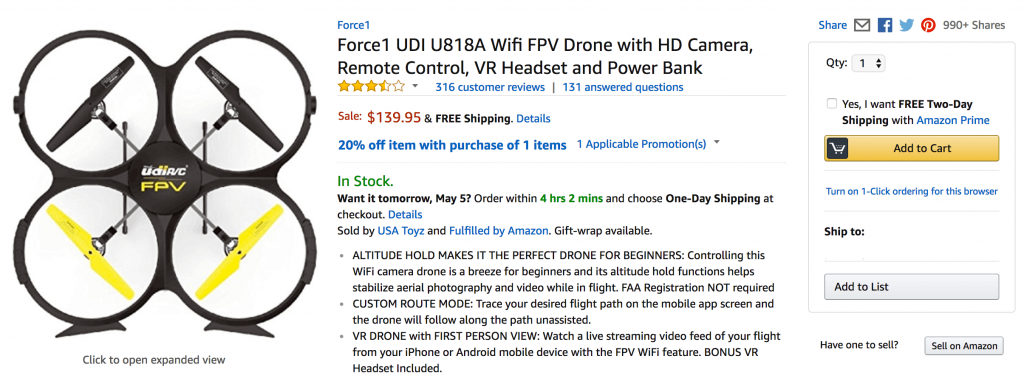

In addition to the DBPOWER drone, another drone that UT’s lab purchased, the Force1 UDI U818A WiFi FPV Drone, has the same vulnerabilities, Valente says. The device, sold by a Bellevue, Wash. company named USA Toyz, contains the same misconfigured FTP server that afforded the researcher Telnet access on the DBPOWER drone, she told Threatpost.

After cross-referencing the devices’ FCC IDs, Valente determined a Chinese company, Udi RC Toys Co. Ltd, manufactures all of the drones. The company, based in Shantou City, also makes RC toy boats, and a VR headset that can be used in tandem with the drones. Vendors such as DBPOWER, Force1, and USA Toyz modify the devices by changing the colors and apps but the functionality of the drones–lack of security included–remain the same, the researcher deduced.

While both drones are popular and available on Amazon, the DBPOWER device is listed as a best seller on the service; earlier this week it was marked down to $79.99 from $139.98.

US-CERT encouraged Valente to contact the vendors directly about the vulnerabilities. She only received one email back, a generic reply from Force1, that failed to address her concern. Neither USA Toyz, Udi RC, or Force1 returned Threatpost’s request for comment.

It’s possible many drones currently on the market have misconfigured FTP servers, Valente said. After reviewing the mobile apps for both the DBPOWER drone and the USA Toyz drone she discovered both apps could control each other’s drones. 10 other drone apps she looked at were found to fly the same drones as well.

Using Telnet access, she learned that it’s likely because both drones have a process, lewei_cam, that listens to TCP ports 9060, 7060, 8060, and UDP 50000. After downloading more than 20 drone apps, many similar to the DBPOWER app, Valente found that 13 of them send the same sequence of network packets over the same open ports on the drone.

“It seems that these commercially available devices are ‘insecure by design’ to enable the proliferation of devices and the reuse of drone apps,” Valente told Threatpost.

While it’s impossible to determine which drones have misconfigured FTP servers without having physical access to each one, Valente points out the number of downloads between all the apps, at least on Android devices, exceeds 200,000. Counting iPhone apps she posits the number of apps that correspond to insecure drones could hover around half a million.

The researcher suggests it could only be a matter of time until attackers harness vulnerabilities like the ones in the U818A drones to carry out further attacks.

“It might not be too long until we start hearing about ‘flying botnets’ of drones infected with self-propagating malware to launch possible DDoS attacks,” Valente said. A recent paper (.PDF) penned by Adi Shamir and other academics, “IoT Goes Nuclear: Creating a ZigBee Chain Reaction,” suggests that something similar – drones spreading an IoT worm from office building to office building – may not be that far fetched.

The researcher suggests there are a number of ways these companies can go about fixing their drones’ security, namely by securing the drone’s access point with a password and implementing a more robust encryption standard. The manufacturers can also limit the number of devices that can connect to the access point, disable its anonymous FTP, and lock down communication between the drone app and the drone.

Consumers may have to sit tight; since these issues appear to be baked into the drones’ firmware and software, it’s unlikely these vulnerabilities can actually be patched. The fact that the vendors, Force1 and USAToyz, aren’t in charge of manufacturing the products complicates things as well.

Security-conscious consumers may have wait for the day drone manufacturers start taking security seriously – if that day comes at all.

“Unfortunately security is not only an afterthought for some drones, but it is a general problem with IoT devices,” Cárdenas told Threatpost Thursday.

“The security of many IoT devices is years behind best-practices, and it is a problem of incentives. Consumers are unaware of the security and privacy practices of an IoT device, and will purchase devices without this information, and because consumers are not demanding better security, manufacturers do not spend more resources in securing their products.”