Being a botnet operator has traditionally been a fairly reliable and easy way to make money. But it’s starting to become a slightly dicier occupation these days, as evidenced by the news of the takedown of the venerable and virulent Rustock botnet by researchers at Microsoft and FireEye.

Being a botnet operator has traditionally been a fairly reliable and easy way to make money. But it’s starting to become a slightly dicier occupation these days, as evidenced by the news of the takedown of the venerable and virulent Rustock botnet by researchers at Microsoft and FireEye.

Rustock has been a major player in the botnet ecosystem for several years and has been a focus of a lot of attention from both law enforcement and researchers. It was a key cog in the global spam and malware economic machine and experts say that Rustock was responsible for sending billions of junk emails a day that pushed a laundry list of garbage products, mainly pharmaceuticals. Estimates put the amount of spam from Rustock at roughly half of the worldwide junk email volume.

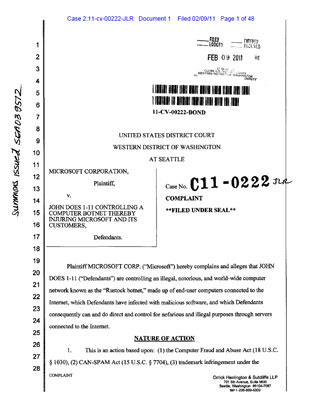

In February, Microsoft filed documents in federal court laying out the structure of the Rustock botnet and explaining in detail what kinds of activities the botnet was responsible for and the economic effect of the botnet’s operations. The company sued a number of unknown parties as well. The takedown occurred on Wednesday, as U.S. Marshals went into several hosting providers’ data centers and seized the command and control servers that ran the Rustock network. This particular botnet was almost entirely contained within the U.S., and the C&C servers that the marshals seized were spread out around the country, in cities such as Denver, Seattle, Kansas City, Scranton, Pa., and Dallas.

In February, Microsoft filed documents in federal court laying out the structure of the Rustock botnet and explaining in detail what kinds of activities the botnet was responsible for and the economic effect of the botnet’s operations. The company sued a number of unknown parties as well. The takedown occurred on Wednesday, as U.S. Marshals went into several hosting providers’ data centers and seized the command and control servers that ran the Rustock network. This particular botnet was almost entirely contained within the U.S., and the C&C servers that the marshals seized were spread out around the country, in cities such as Denver, Seattle, Kansas City, Scranton, Pa., and Dallas.

The takedown operation on Rustock involved a wide range of companies and law enforcement agencies in addition to Microsoft and FireEye, including the Dutch High Tech Crime Unit, the University of Washington, CN-CERT in China and Pfizer, the pharmaceutical giant. Rustock is one of the older botnets that was still in operation, having first emerged about five years ago.

This is the second major botnet disruption that Microsoft has initiated, coming roughly a year after the company went after the Waledac network with similar tactics. That operation was deemed a success at the time, although Waledac has returned in a somewhat diminished form since then.

“However, Rustock’s infrastructure was much more complicated than

Waledac’s, relying on hard-coded Internet Protocol addresses rather than

domain names and peer-to peer command and control servers to control

the botnet. To be confident that the bot could not be quickly shifted to

new infrastructure, we sought and obtained a court order allowing us to

work with the U.S. Marshals Service to physically capture evidence

onsite and, in some cases, take the affected servers from hosting

providers for analysis,” Richard Boscovich, senior attorney in Microsoft’s Digital Crimes Unit, said in a blog post on the Rustock takedown. “Specifically, servers were seized from five

hosting providers operating in seven cities in the U.S., including

Kansas City, Scranton, Denver, Dallas, Chicago, Seattle, Columbus and,

with help from the upstream providers, we successfully severed the IP

addresses that controlled the botnet, cutting off communication and

disabling it. This case and this operation are ongoing and our

investigators are now inspecting the evidence gathered from the seizures

to learn what we can about the botnet’s operations.”

Microsoft has taken an interest in disrupting various botnets for a couple of reasons: the huge amount of spam that they spew is a major problem for the company’s customers and Hotmail service; and many of the spam messages from the botnets tout fake Microsoft products or entice users into opening malicious attachments by couching them as Microsoft updates or security patches. The company’s experts estimated that there are roughly one million PCs infected by the Rustock bot, and the reality is that as long as there is a crew behind Rustock that’s interested in making money, the botnet will have a good chance of returning in some form.

“Bot-herders infect computers with malware in a number of ways, such

as when a computer owner visits a website booby-trapped with malware and

clicks on a malicious advertisement or opens an infected e-mail

attachment. Bot-herders do this so discretely that owners often never

suspect their PC is living a double life.

It’s like a gang setting up a drug den in someone’s home while

they’re on vacation and coming back to do so every time the owner leaves

the house, without the owner ever knowing anything is happening,” Boscovich wrote.

Takedowns such as those targeting the Rustock, Waledac and Cutwail botnets are important tactics in the fight against spam, malware and other forms of online crime. However, there always are other groups willing to take up where a current botnet operator left off and take the risks that come along with that. And there also is a seemingly endless supply of hosting providers that are willing to look the other way when it comes to providing services for C&C operations.