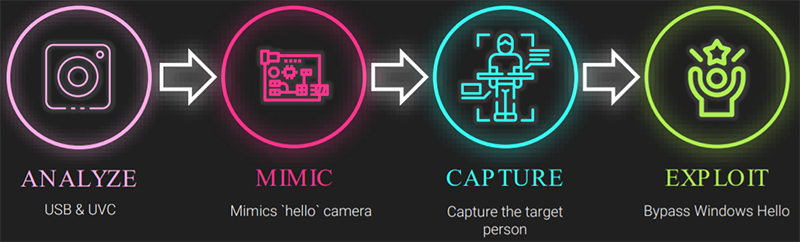

LAS VEGAS – Microsoft Windows 10 biometric user authentication systems Windows Hello can be bypassed, using a single infrared image of a user’s face planted on a tampered clone of an external USB-based webcam.

The vulnerability, tracked as (CVE-2021-34466, CVSS score: 5.7), was patched by Microsoft in July. However, according to research disclosed here at Black Hat USA 2021, the flaw still allows attackers – in some scenarios – to bypass Windows Hello and Windows Hello for Business, used for single-sign-on access to a user’s computer and a host of Windows services and associated data.

Security research Omer Tsarfati, with CyberArk Labs, outlined his research (dubbed Pass-the-PRT attack) that leveraged a custom-made USB device containing a spoofed image of a Windows 10 user.

“All you need is a valid infrared frame of the target, which can be obtained relatively easily. Next, you need to take that data and put it into a cloned USB-based camera and plug it into the Windows 10 system targeted,” Tsarfati said.

It may sound like an easy hack, but the attack requires some heavy lifting on the adversary’s part.

CyberArk’s Omer Tsarfati shows Threatpost the NXP (i.MX RT1050) circuit board used to mimic a USB camera to bypass Windows Hello.

What is a Pass-the-PRT Attack

Giving a nod to previous research on Windows ecosystem’s tokens and encryption keys by Benjamin Delpy and Dirk-Jan Mollema, Tsarfati said his hack also sidesteps the need to acquire Azure AD (Active Directory) Primary Refresh Tokens (PRT) used for single sign-on access to Windows.

For this reason, he calls the vulnerability a Pass-the-PRT bug. Similar to Pass-the-Hash and Pass-the-Ticket, a Pass-the-PRT attack, is serious, given the fact that it gives an adversary access to not just local systems, but also Azure-related resources such as MSFT 365 assets.

The soft underbelly of the Windows Hello biometric authentication platform, which includes PIN, fingerprint and facial recognition, is the reliance on the biometric sensor (camera), the research explained.

“At the heart of this vulnerability lies the fact that Windows Hello allows external data sources, which can be manipulated, as a root of trust,” Tsarfati said.

Hardware Hack Explained

The relatively easy part of the hack was capturing the infrared image frame of a targeted victim. “With a $50 camera from a consumer electronics store you can easily capture a photo of the target. The hard part requires much more than an infrared image,” he said. The challenge for Tsarfati was cloning the camera and the specific design descriptors that Windows uses to validate and trust an external USB camera. These are used with Microsoft’s Windows Hello system to secure a USB session handshake by camera or webcam devices.

“USB has a strict tree network topology and master/slave protocol for addressing peripheral devices. Once a USB device is connected to the computer bus via the USB port, the host starts a session with the peripheral device. After the session is established between the host and the USB device, the host will send multiple requests to identify the USB device, called descriptor requests,” according to a technical breakdown posted by CyberArk.

The post continues: “The host can’t identify which device is connected to the USB port, and therefore it needs to get the information from the connected peripheral device. As unbelievable as it sounds, it means that every device can present itself as whatever it wants, and the host can’t verify this. At least there is nothing in the specification that defines such a process.”

Using tools (USBPcap and Wireshark) to capture the URB (USB Request Blocks) packets sent and received by the targeted PC to communicate and validate the Windows Hello authentication, researchers were able to clone a USB camera on a NXP circuit board with IR and RGB sensors. Next, they needed to understand how the cloned USB-based camera defined itself in terms of its USB capabilities and features via “descriptors that define the device interfaces, alternate settings and endpoints.”

“We aimed to create a clone that will act as the real camera, so we copied the configuration and the device descriptors,” Tsarfati said.

Easier said than done.

Through massive trial-and-error, reverse engineering the USB descriptor specifications and cloning the precise USB handshake used by Windows Hello, the researcher finally hit pay dirt. “Once you have correctly captured and placed the frames in the custom USB camera, you will be able to bypass the login screen,” he said.

Video Demo of (CVE-2021-34466) Hack and Attack

Not a Perfect Patch

After five months of working with Microsoft on validating and breaking down the bug, Microsoft delivered a patch this past July.

“Microsoft did release a fix that restricts the number of camera brands it supports with Windows Hello and restricts external cameras, unless a user permits,” he said. “If the external camera restrictions are disabled by the user, the bypass still is possible.”

Microsoft responded to CyberArk research, explaining that its July Patch Tuesday mitigation includes an allow list of USB devices that are trusted to be used in the Windows Hello authentication phase. “Microsoft released a security update on July 13 that mitigates this issue,” it stated.

“In addition, customers with Windows Hello Enhanced Sign-in Security are protected against such attacks which tamper with the biometrics pipeline,” Microsoft said in a statement. “Enhanced Sign-in Security is a new security feature in Windows which requires specialized hardware, drivers, and firmware that are pre-installed on the system by device manufacturers in the factory.”

CyberArk responded on Wednesday, stating: “According to our current assessment, exploitation of the vulnerability is still possible via duplication of an external trusted USB device due to the way trust is established.”

Researchers reported the vulnerability to Microsoft in March 2021. Microsoft acknowledge the vulnerability a month later. Microsoft published an advisory regarding mitigations on July 13.

Worried about where the next attack is coming from? We’ve got your back. REGISTER NOW for our upcoming live webinar, How to Think Like a Threat Actor, in partnership with Uptycs. Find out precisely where attackers are targeting you and how to get there first. Join host Becky Bracken and Uptycs researchers Amit Malik and Ashwin Vamshi on Aug. 17 at 11 a.m. EST for this LIVE discussion.