Mobile carriers have left the door wide open to SIM-swap attacks, particularly when it comes to prepaid accounts, researchers have found.

SIM swapping is a form of fraud that allows crooks to bypass SMS-based two-factor authentication (2FA) and crack online banking or other high-value accounts. According to PhishLabs, a typical attack would start with an attacker phishing personal and banking information – often via SMS phishing, which has the added benefit of confirming that a victim’s cell phone number is an active line. Then, the next step is to call the person’s mobile carrier – easily discovered with an online search – and ask to port the line to a different SIM card/device.

Here’s where the issue comes in: Many carriers don’t ask in-depth security questions that fully verify that the caller is in fact the legitimate cell phone user, according to a recent academic experiment. Thus, fraudsters are able to transfer the line to a device that they control – thereby putting themselves into position to intercept 2FA text codes. From there, it’s easy to use the previously phished information to gain access to and take over an account.

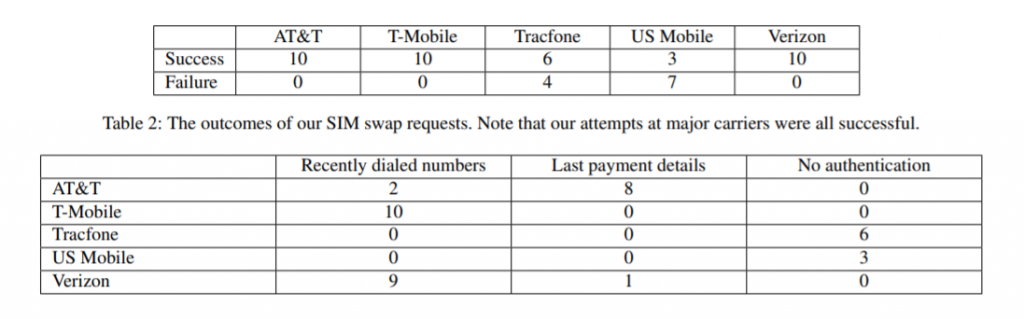

The primary check in this kill chain should clearly be the mobile carrier’s verification processes. However, according to a recent Princeton University study, researchers tested five North American prepaid telecom companies (AT&T, T-Mobile, Tracfone, US Mobile and Verizon Wireless) to see if they could successfully port their own number to another SIM card. In trying 10 times each with each carrier, they found that they could do so in most cases, thanks to a lack of strong verification processes.

“All five carriers used insecure authentication challenges that could easily be subverted by attackers,” according to the report. “We also found that in general, callers only needed to successfully respond to one challenge in order to authenticate, even if they had failed numerous prior challenges. Within each carrier, procedures were generally consistent, although on nine occasions across two carriers, [customer service representatives] CSRs either did not authenticate the caller or leaked account information prior to authentication.”

Further, the experiment was structured so that no advanced fraud tactics were used.

“Our simulated attacker knew only information about the victim that would be easily accessible without overcoming any other security measures,” the report explained. “Specifically, our attacker knew the victim’s name and phone number. We also assumed that the attacker was capable of interacting with the carrier only through its ordinary customer service and account refill interfaces.”

The researchers began by telling the CSRs that they needed to use a new SIM card because the old one was faulty. After that, CSRs typically posed authentication questions, usually asking for one of the following: An account PIN, recently dialed numbers (call logs), personal information like date of birth or billing address, model numbers or other device information, answers to security questions (i.e., “in what city were you born”), and so on.

If the callers could not answer an authentication challenge correctly, the tactic was to claim to have forgotten the information or to provide incorrect answers.

“When providing incorrect answers to personal questions such as date of birth or billing ZIP code, [research assistants] would explain that they had been careless at signup, possibly having provided incorrect information, and could not recall the information they had used,” the report outlined.

The CSRs would then often provide hints, which could help the “attackers” to locate the correct information via online searches.

The results of the SIM-swap attempts are collected below:

Many of the authentication methods could be subverted with slightly more sophisticated attack skills, the report noted. For instance, to provide an outgoing number from the call log, an attacker could send the victim a vague text asking for a callback for some purported urgent request. In order to capture device information, a malicious app could be employed to harvest it. If asked for the date or amount of the last payment, an attacker could purchase a refill card at a retail store, submit a refill on the victim’s account, then request a SIM swap using the known refill as authentication.

It may seem like a lot of effort to subvert some of these authentication challenges, but the payoff can be huge when you’re talking about corporate targets. PhishLabs pointed out in a Thursday posting on the attack method that Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey was a victim of the tactic; and in another known case, an attack resulted in the victim having a Coinbase account emptied that was worth around $100,000 in cryptocurrency.

“Though still uncommon, mobile phone customers in the U.S. and Canada are the prime targets of these attacks and their private accounts such as their banking information is the end goal,” the firm said.

After disclosing the findings to the carriers in question, the Princeton researchers got little response. They noted: “In July 2019 we provided an initial notification of our findings to the carriers we studied and to CTIA, the U.S. trade association representing the wireless communications industry. In January 2020, T-Mobile informed us that after reviewing our research, it has discontinued the use of call logs for customer authentication.”

Threatpost reached out to the carriers for comment.

The research echoes previous findings that also illustrated the lack of strong authentication at mobile carrier call centers. At the Security Analyst Summit in Singapore last year, David Jacoby, a Swedish member of Kaspersky’s global research and analysis team (GReAT), explained how Swedish telcos ask only for a bare minimum of information from callers – and publicly available information at that – before agreeing to make account changes to specific numbers. This has led to real-world attacks where victims have found their mobile phone calls hijacked and redirected to a rogue number.

In terms of mitigation, some say that relying on standard fraud-detection technologies isn’t a perfect solution for corporations looking to protect themselves from these kinds of attacks.

“There are two approaches you can use to combat SIM-swap attacks, namely detection and prevention,” said Dewald Nolte, chief commercial officer at Entersekt. “Due to the way that the industry uses SMS-based verification codes, detection is not always a fail-safe way of eliminating this type of attack. It can certainly make life more difficult for the perpetrator, but there are advanced techniques available to get around most of the detection techniques.”

In its writeup, PhishLabs noted that targeted organizations can instead reduce the threat of SIM-swap attacks to account security by using 2FA methods that can’t be exploited remotely, such as security keys that require the user to have physical possession of a token to unlock an account.

Concerned about mobile security? Check out our free Threatpost webinar, Top 8 Best Practices for Mobile App Security, on Jan. 22 at 2 p.m. ET. Poorly secured apps can lead to malware, data breaches and legal/regulatory trouble. Join our experts from Secureworks and White Ops to discuss the secrets of building a secure mobile strategy, one app at a time. Click here to register.