First of all, we feel it necessary to clarify some of the confusion surrounding the files and their names related to this incident. To get a full understanding of the situation you only need to know that we’re talking about just two malicious programs here (at a minimum) – the main module and a keylogger. All that has been mentioned in last 24 hours about connections between Duqu and Stuxnet is related mostly to the first one – the main module.

The main module consists of three components:

- a driver that injects a DLL into system processes;

- a DLL that has an additional module and works with the C&C; and

- a configuration file.

The module is very similar to Stuxnet – both in structure and in behavior. However, the name Duqu has almost no connection with it. This name is based on the names of the files that are related to a completely different malicious spy-program!

This second malicious program, which is basically a keylogger (but is also able to collect other types of information) was discovered on the system of one of the victims together with the main module described above. Because of this fact, plus the main module’s ability to download other components, it was assumed that the main module and the keylogger were somehow related to each other. While working in a system, the keylogger stores collected data in files with names like ~DQx.tmp. So the name of the main module – Duqu – was given based on these files.

But actually, the code of the Trojan-Spy in part proves the connection between it and the main module, and it was probably downloaded by the main module sometime earlier. But as per its functionality, it is an independent malicious application able to work without the main module. At the same time, the main module is able to work without the Trojan-Spy. However, the connection between the keylogger and Stuxnet is not so obvious, and that’s why it’s possible – at a stretch – to perhaps call it a grandchild of Stuxnet, but certainly not its child 🙂

A year ago during our analysis of Stuxnet we concluded that it consists of two parts: a carrier platform, and a separate module responsible for PLC. In fact, Stuxnet is rather like a real-life missile with an overclocking module (a worm itself) and a warhead (PLC module).

We suggested that Stuxnet was developed probably by two different groups of people who may not have known about each other’s existence or the ultimate aim of the project.

The part of Stuxnet responsible for its spread and system infection might be used again, but with a different ‘warhead’.

And that’s similar to what happened with Duqu. However, Duqu had no ‘warhead’, but it was able to install any ‘warhead’ at any moment and aim it at any target.

What is needed is clarification of the sequence of events that are known and which can be disclosed.

The History of Duqu’s File Discovery and Detection

Trojan-Spy

The first “date” between Duqu and antivirus vendors took place on September 1, 2011, when somebody from Hungary sent a file named ~DN1.tmp to Virustotal for scanning.

The name of the file indicates that it was probably found on an infected machine. The file was not a component of the main module, but a Trojan-Spy, and was probably installed on a system already infected by Duqu.

The file was detected at the moment of submission by four products – actually, just two antivirus engines: BitDefender (as Gen:Trojan.Heur.FU.fuW@aGOd0Wpi), and AVIRA (as TR/Crypt.XPACK.Gen3); F-Secure and G-DATA use BitDefender’s engine.

This is very interesting. It indicates that the authors of Duqu were not all that worried about detection of this module by specifically these four antivirus programs. However, these detections helped uncover the module.

After the initial detection, the file was added by many antivirus companies to their databases – from September 9 to 19 mostly. Kaspersky Lab added this file to its database as Trojan.Win32.Inject.bjyg on September 14. On the same day Microsoft added it too (Trojan:Win32/Hideproc.G).

It could have been possible to think that signature detection of this file by a number of antivirus programs meant that the Duqu main module should also be detected. However, the situation was totally different.

Driver

The first “real” Duqu file was also sent for scanning to Virustotal, also probably from Hungary. This took place on September 9.

The file was sent with its original name cmi4432.sys, and it indicates the variant of the driver, which has a C-Media digital signature.

None of the 43 Virustotal antivirus programs detected it – neither on September 9 (the first submission of the main module to Virustotal), nor on October 17 (when information about Duqu was published). All detections were added after publication.

This indisputable fact proves that Duqu’s authors were very careful while creating it. Despite the similarity with Stuxnet, they were able to change the code and bypass detection by all popular antivirus programs.

It’s interesting to see the correlation between the exact time of file submission in Hungary to Virustotal, and the public information about the files which was available earlier. What we’re talking about here are posts by a Hungarian blogger (see www.securelist.com/en/blog/208193178/Duqu_FAQ), especially those on September 8 where he points out the MD5 of the file: the main module and the Trojan-Spy!

Looking for friends of foes of 9749d38ae9b9ddd81b50aad679ee87ec to speak about. You know what I mean. You know why. 0eecd17c6c215b358b7b872b74bfd800 is also interesting. b4ac366e24204d821376653279cbad86 ?

We investigated this situation and concluded that the Hungarian blogger probably works for Data Contact (www.dc.hu), an ISP/ Hoster and Certification Authority in Budapest. Probably this company or its clients found these files on their PCs.

Frankly speaking, we, as well as some other antivirus vendors, know at least one other company in Hungary that became a victim of Duqu. But at the moment this information cannot be disclosed.

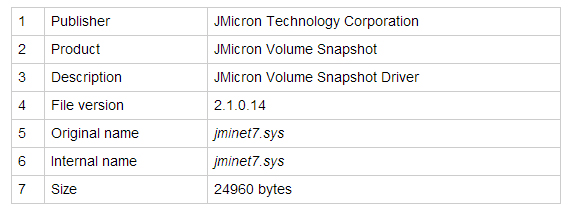

The second variant of the driver was also submitted to Virustotal and was also probably from Hungary. This happened on September 18 and the file’s original name is jminet7.sys.

This variant has no digital signature and passes itself as a file from JMicron.

And again, as was the case with the first driver, we didn’t see any detections on Virustotal until October 18.

No PNF files which are encrypted DLLs and configuration files for drivers have been spotted on Virustotal, and no antivirus vendors got hold of these files until the first official publication about Duqu.

The Story Continues…

However, since collecting all the information about Duqu and publishing it, new files of this malware have been found. This means that Duqu’s authors are monitoring the situation, are reacting to events, and are not going to stop.

Third Driver

A new driver was found on October 18 – with a new date of creation and new file information. On October 19 this file was submitted to Virustotal by two different sources – in Austria and in Indonesia – almost at the same time (an 18-minute interval)!

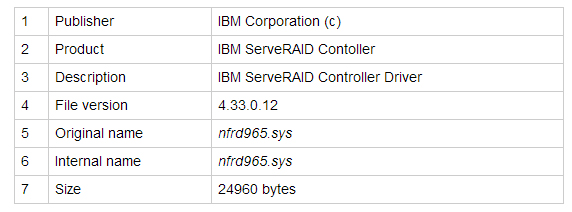

The new variant passes itself as an IBM driver:

It has no digital signature and was compiled on October 17.

Fourth Driver

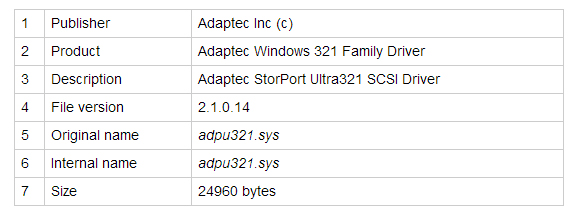

We received a new driver via Virustotal on the night of October 20, which is different from the previous ones. It was sent from the UK.

It also has no digital signature and also was compiled on October 17 (the same date as the IBM driver).

Have a look at the file name: adpu321.sys. This becomes significant and interesting in the next part of this tale…

Target: the Whole World?

Recall the Stuxnet story. We and other antivirus companies spotted tens of thousands of infections (especially in Iran) right after its discovery and detection. This gave a rather unambiguos indication of the probable target, and further investigation confirmed this theory.

But what about Duqu’s infection map? We used our cloud-based Kaspersky Security Network, which allows us to track any malicious activities on clients’ systems.

The results are surprising. We found just ONE real infection in the 24 hours after adding the detection of all the modules!

And the country where the infected user is based is highly specific, and completely different to all the countries mentioned in this report above (Hungary, Austria, Indonesia, the UK).

We’re currently trying to contact the user to be able to conduct a deeper investigation and search for the missing Duqu components that are probably in the infected system. For now we can only point out that the malicious driver that was found there has a completely different name – adp95xx.sys (similar to adpu321.sys). This means that THREE different Duqu drivers have been found in the last 48 hours. And it is possible that there are more of them.

It is essential to mention that we can observe only one Duqu main module infection; we don’t see any Trojan-Spy infections. This means that:

- the client is infected with an unknown malicious module; or

- there is no ‘warhead’ in this case.

De facto, this means that Duqu may exist in different variants, e.g., not necessarily with a keylogger, which is claimed to be the only known malicious module. In our view other modules – able to do come what may – could exist.

Unlike Stuxnet, which infected many systems but looked for a specific target, Duqu infects a very small number of very specific systems around the world, but may use completely different modules for every system.

Moreover, at the moment no one has found the installation file (dropper), which has to be the first link in the infection chain – responsible for both the driver and DLL installation.

This file might be a worm and use various exploits.

This file is the key to solving the Duqu puzzle.

Our search for it continues…

UPDATE

Right after publication we found an interesting link (http://systemexplorer.net/db/adpu321.sys.html) that contains information about one more Duqu driver. It has the same file name as the fourth file that we describe (adpu321.sys). But, as you may notice, it was discovered on 21 September and the file described by us was created on 17 October! This merely emphasizes our belief that there may well be many Duqu drivers out there that continue to go unnoticed (but which can be detected).