Many digital trees have died for the cause of informing Windows admins about the SMBv1 vulnerability that spawned the WannaCry and ExPetr/NotPetya malware attacks. Yet a relatively small sample of data collected from a freely available tool shows that thousands have not gotten the message, or have some significant blind spots in their networks.

“There are always blind spots,” said Elad Erez, director of innovation at Imperva, who built the scanner called EternalBlues. “If you have 10,000 computers, can you really be that sure (that all hosts are patched)? You can’t. You need someone or something to help you with it.”

The scanner was made available in late June, and statistics collected from individuals and organizations that downloaded EternalBlues and ran it in their environments were published yesterday.

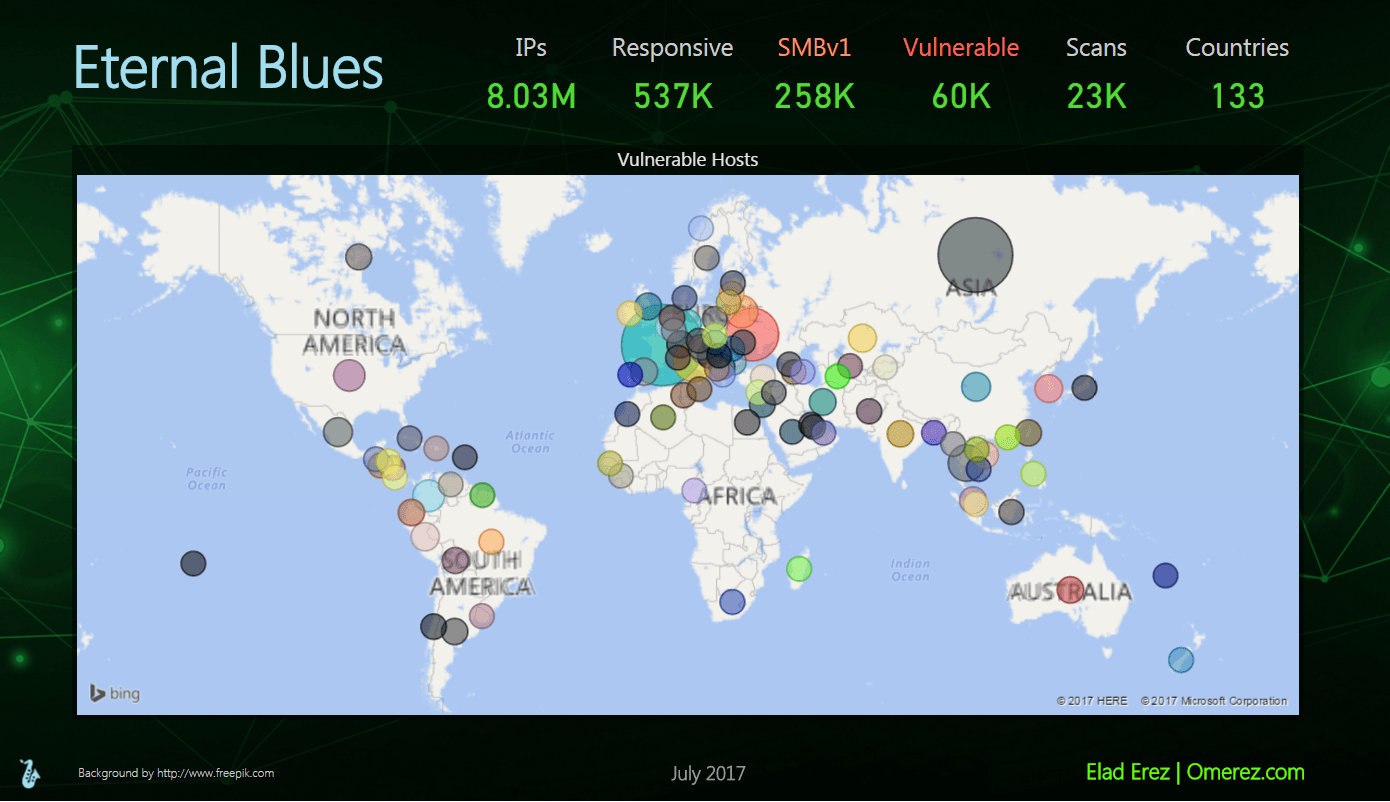

More than 8 million IP addresses (not hosts) were scanned by EternalBlues in 12 days, with 537,000 of those responding on port 445, the port over which SMB communication happens. Erez’s statistics show that 258,000 of those hosts were running the 30-year-old SMBv1 protocol, and 60,000 of those were vulnerable to the NSA’s EternalBlue exploit leaked by the ShadowBrokers.

WannaCry and ExPetr/NotPetya infected networks worldwide, with a heavy concentration of victimized machines in Russia and the Ukraine; Erez said one scan in the Ukraine uncovered 1,351 vulnerable hosts. WannaCry contained its own worming functionality in that once it infected machines, it began scanning the internet for other vulnerable hosts. ExPetr, meanwhile, was a wiper attack disguised as ransomware; the ransomware component of that attack was faulty and experts said it was clear the attackers never intended to decrypt compromised data or collect any money. Instead, the malware overwrote the Master Boot Record (MBR) on infected machines, leaving them useless.

Tools such as EternalBlues and others, Erez said, are vital for large networks, even those that may have applied the MS17-010 patch eradicating EternalBlue. One vulnerable endpoint is enough for either of these attacks to succeed. Erez said he built the tool for such a use case, as well as for smaller businesses that are unlikely to have IT or security teams responsible for patching or backups, the two strategies most important to countering ransomware attacks.

The results of the first 12 days of scan data surprised Erez.

“I thought it would be maybe 7 percent to 8 percent of hosts out there that would be vulnerable. It turned out to be 11 percent, a bit higher than I thought,” Erez said. “About one of nine hosts on the network is vulnerable. And who thought that more than half (53.9 percent) would still be open to this protocol?”

Awareness, however, may not be the entire cause, rather a lack of total visibility, especially into large enterprise networks, Erez said.

“People in the industry really know about the problem and are well aware that they need to mitigate it somehow. Running my tool, by definition, means they were well aware of the problem,” Erez said. “While there’s pretty good awareness from those who downloaded my tool, I don’t think [awareness] got to that second segment of users who are less sophisticated and don’t come from the tech industry—smaller businesses. I don’t think it made it to there. I really wanted to make this tool for smaller businesses who don’t have backups, who are more likely to pay, to help them before the next attack.”