When CrowdOptic, a Silicon Valley, venture funded startup, developed a cool application that could stream real-time, context-aware information streams to mobile devices, the applications seemed straight-forward (and lucrative) enough: a blend of advertising and broadcasting that sports franchises and concert promoters might use to create an enhanced and “immersive experience” for fans attending live events. Along the way, however, the company discovered another, even more powerful use for their technology: crowd control.

The “ah ha” moment for CEO Jon Fisher came at his fledgling company’s first big test: the 2011 Bank of the West Tennis Tournament, which was held at Stanford University. The event, staged by CrowdOptic customer and sports promoter IMG Worldwide, gave CrowdOptic a chance to show IMG what its technology could do. Dozens of IMG and CrowdOptic users, including Fisher himself, were positioned in the audience, each with mobile devices outfitted with a photo sharing app running the company’s mobile application, which blends GPS and compass coordinates and on-board video cameras with realtime data feeds provided by the United States Tennis Association (USTA).

“Hold the phone up and point it at Maria Sharapova when she’s serving and, right in the camera viewer, you could see her second serve percentage,” Fisher recalled in an interview with Threatpost. But a funny thing happened: half way through the match, someone driving on the boulevard outside Stanford stadium peeled out while blasting their horn.

“I shifted my head to see what was going on, and so did everyone around me,” Fisher recalls. “I was receiving realtime data on the people on our system. At that moment, we had 38 concurrent users on the system, and all but a few disappeared. Instead of focusing on the action (on court), they had shifted their perspective.”

That gave Fisher an idea. His previous company, Bharosa, sold anti fraud technology to banks and credit unions. Fisher eventually sold the firm to Oracle Corp. Maybe there was a security application for CrowdOptic, also.

“Bharosa was about authenticating users based on the device they were using and their tendencies — the contextual authentication piece,” Bharosa recalls. “There is a clear parallel here with device analysis. If you understand the context of a live crowd, thing get very interesting from a security perspective.”

Go to a concert or sporting event today, Fisher notes, and “every kid has a phone in the air.” Those devices are belching data. “I can know in real time what they’re focusing on by monitoring real time attributes like GPS, compass heading. We can triangulate between two users and a cell tower to get their location,” he said.

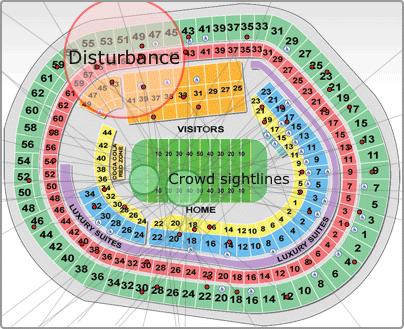

Fisher’s engineers developed algorithms to smooth out the data – a scattered and noisy “digital exhaust” of smart phones and other mobile devices. That allowed CrowdOptic to identify sudden changes in the orientation of phones running the company’s application, as individuals in a crowd react to sudden events or changes.

“This is better than security guards. We have the ability to detect neural disturbances – that first look at what’s happening,” he said. In crowds of 50,000 or 100,000 people, that can make the difference between a fistfight turning into a melee.

Of course, services like CrowdOptic also raise the specter of ubiquitous, intelligent and automated surveillance – a scary prospect in a society that’s already struggling with the privacy implications of new, powerful mobile devices and ubiquitous Internet connectivity.

Security researchers have already raised alarm about mobile applications, such as the Pandora app, that ravenously grab data from devices on which they are installed – often far in excess of the application’s purpose and with scant warning to users beyond obscure legalese buried in end user license agreements. Beyond the privacy concerns, virus researchers have warned that geolocation data could help attackers create user and context-specific social engineering and malware attacks.

Fisher isn’t worried. All the data collected from CrowdOptic applications is anonymized, he said. “We don’t know anything about any of these users.” Beyond that, Fisher said that the CrowdOptic technology can make correct inferences about the behavior of large crowds based on the data of only a few hundred users. Those users would willingly install the application to get premium content. CrowdOptic is in the process of bundling its technology with popular applications or event-specific apps created by promoters, sports franchises and the like.

The model, he said, is really little different than other “free” mobile applications, which harvest minute details about users’ location, preferences and activities in exchange for access to cool features and content. In that way, Fisher sees his company as a logical successor to location-based services like FourSquare. “Geolocation services are cute, but the real value is knowing what the user is focusing on, not just that they’ve arrived at a location,” he said.

That kind of granular data on individuals’ interests is a gold mine for advertisers, who are looking for ways to enable more and more personalized advertisements. With widespread deployment at big events, Crowdoptic could tell promoters and their advertisers which moments during the tournament were the most photographed, for example. At Bank of the West, CrowdOptic data revealed that users focused on player Maria Sharpova far more when she was playing at the net than when she was at the serve line, Fisher said.

Besides, he argues, the data aggregated across a crowd could help first responders locate injured people or respond to a disturbance. “Your privacy is already encroached upon on Facebook. All we’re doing is taking anonymized data that might save 20 seconds in responding to a life-saving situation.

For now, the security features are in beta and Fisher is focusing more on the advertising potential of his technology. The firm has raised $1.5m in venture funding from investors, including Bowman Capital. But Fisher’s company is already working with Andrews International, a security firm, to use the technology to detect and respond to “emergencies in real time” during the events the firm manages

“With CrowdOptic, we will be able to surveil the crowd and support our personnel with a stronger arsenal than onsite security cameras,” said Randy Andrews, CEO of Andrews International in a company press release. “We will be able to respond faster in situations in which every second matters crucially; as well as deploy our resources in a more efficient and effective model.”