Facebook users are sharing less information publicly, yet continue to share countless bits of information with what one group of researchers has dubbed “silent listeners.”

The researchers, from Carnegie Mellon University, recently wrapped up the world’s first multiyear, longitudinal privacy study of the site. The study relies on a slew of information harvested from Facebook users who were members of the school’s network over the course of seven years.

In the corresponding paper, “Silent Listeners: The Evolution of Privacy and Disclosure on Facebook,” (.PDF) researchers Alessandro Acquisti, Ralph Gross and Fred Stutzman analyze the security practices of 5,076 Facebook users over time, comprising what the researchers call the Carnegie Mellon Yearly Snapshot Dataset, a swathe of information taken from users of the site spanning Facebook’s infancy in 2005 through the site’s rapid public expansion to 2011.

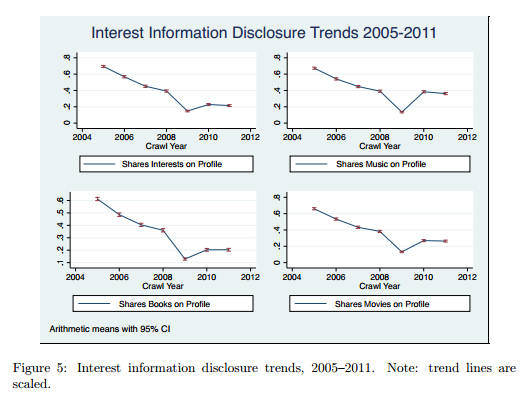

Across that time it was found that users gradually began to limit how much personal information they divulged on the internet, as most individuals elected to share less information with unconnected, public profiles.

Users weren’t as forthcoming in 2009 as the corresponding graphic may suggest. Changes to the site’s interface over the years appear to have directly implicated how some users handled their privacy; at some points even inverting results the group had initially received.

When Facebook sprung a new system on users in 2009 that converted interests to public “likes,” users were caught off guard. The way the study translated all of those statistics made it seem like users were sharing more information publicly when really, the majority of users were oblivious victims to change.

While public sharing eventually decreased – be it attributed to users wanting to protect their information or realizing they were essentially “negotiating with a service” – user shares between actual Facebook friends soon started to increase.

The study notes this may have coincided with certain points in Facebook’s history. After status updates were introduced in 2006 and Timeline was introduced in 2011, it became much easier for users to share private information between connected friends.

“They increased their disclosures to other entities as well: third-party apps, advertisers, and Facebook itself,” according to one chapter of the paper, “The Silent Listeners.”

Third party apps, which can create additional data points for users, shouldered most of the blame for increased sharing in the report.

Third party apps, which can create additional data points for users, shouldered most of the blame for increased sharing in the report.

Naturally, users who link Facebook with Foursquare are also sharing their check-ins with Facebook, just like how users that connect Facebook with Spotify are sharing their musical tastes. These are all what the study refers to as added data points.

Facebook users could begin tagging other people in photos in 2006 and tag their location in 2010. This translates to even more added data points.

That, along with user information given up by Facebook to entities of its choosing (law enforcement, etc.) and the information from private fields that is ultimately given to advertisers comprise a significant uptick in shared personal information that oftentimes, users are completely unaware they’re sharing. It’s these apps and entities that are ultimately likened to as “silent listeners” in the trio’s paper.

Facebook users may have become wiser to the ways of data collection over time, but appear to grow further perplexed by the data-hungry third party apps and advertisements that muddle their news feed each day.

Acquisti, one of the CMU researchers, has discussed how Facebook and the privacy realm intersect with Threatpost before. Acquisti gained notoriety a few years ago after his “Faces of Facebook” talk at Black Hat posited that one day it’d be possible to use technology to connect a user’s Facebook profile picture to their social security number. At the time – and in a paper authored in 2009 he called it “a blending of online and offline data.”

Earlier this year, Facebook unveiled its “Graph Search” tool, a tool to help users search for other users based on common interests, triggering some critics to question whether the site is becoming more of a privacy pressure cooker. Privacy experts have argued the service could be a goldmine for phishers, spammers and those looking to execute social engineering tricks. Christopher Hadnagy, owner of White Hat Defense insisted “this is how bad guys get to you and hack you,” when discussing the drawbacks to the new “Graph Search” function. Those looking to target certain individuals via a spearphishing attack don’t have to search long to find names and potential e-mails for their victims, Facebook is laying it all out for them.