The Flame malware uses several methods to replicate itself. The most interesting one is the use of the Microsoft Windows Update service. This is implemented in Flame’s “SNACK”, “MUNCH” and “GADGET” modules. Being parts of Flame, these modules are easily reconfigurable. The behavior of these modules is controlled by Flame’s global registry, the database that contains thousands of configuration options.

SNACK: NBNS spoofing

The SNACK module creates a RAW network socket for either all or pre-set network interfaces and begins receiving all network packets. It looks for NBNS packets of other machines looking for local network names. When such a packet is received, it is written to an encrypted log file (“%windir%temp~DEB93D.tmp”) and passed on for further processing.

When a name in the NBNS request matches the expression “wpad*” or “MSHOME-F3BE293C”, it responds with its own IP address. If “SNACK.USE_ATTACK_LIST” variable is set to “True”, it also checks whether packets originate from IP addresses specified in its “SNACK.ATTACK_LIST” and responds to machines with these addresses.

“Wpad” is a name used for automatic proxy detection. By responding to “wpad” name requests with its own IP address, the SNACK module announces the infected machine as a proxy server for its local network.

SNACK and MUNCH also communicate with the GADGET unit that provides facilities for handling different events that come from other modules. The Flame’s registry contains LUA modules for processing events like “MUNCH_ATTACKED”, “SNACK_ENTITY.ATTACK_NOW”.

MUNCH: Spoofing proxy detection and Windows Update request

“MUNCH” is the name of the HTTP server module in Flame. It is started only if “MUNCH.SHOULD_RUN” variable is set to “True” and there are no running programs that can alert the victim. These programs (anti-virus, firewalls, network sniffers etc.) are defined in the Flame’s registry in a list called “SECURITY.BAD_PROGRAMS”

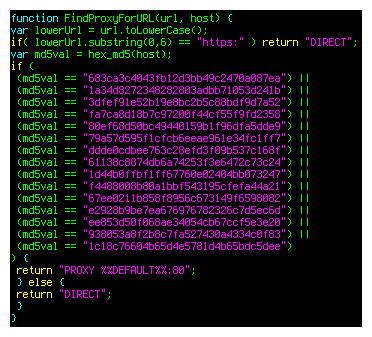

When MUNCH is started, it reads a buffer from the “MUNCH.WPAD_DATA” variable, replaces the pattern “%%DEFAULT%%” with the IP address of its best suitable network interface and waits for HTTP requests.

Contents of the “MUNCH.WPAD_DATA” variable

The “MUNCH.WPAD_DATA” buffer is actually a WPAD file that is requested by network clients that implement automatic proxy server detection. The code in the WPAD file matches the MD5 hash of the hostname that the client is connecting to against its own list, and if found, offers itself as a HTTP proxy. We were able to identify some of the hashes:

download.windowsupdate.com

download.microsoft.com

update.microsoft.com

www.update.microsoft.com

v5.windowsupdate.microsoft.com

windowsupdate.microsoft.com

www.download.windowsupdate.com

v5stats.windowsupdate.microsoft.com

So, when a machine configured with automatic proxy detection tries to access one of the Windows Update hosts, it receives an IP address of the infected machine from SNACK, and then receives the IP address of the same machine as a proxy server from “wpad.dat” provided by MUNCH. From then, requests to the Windows Update service are passed through the MUNCH server.

When a network client connects to the MUNCH server and requests an URI other than “/wpad.dat” and “/ view.php”, the server:

1) Runs “MUNCH.SHOULD_ATTACK_SCRIPT” – Lua script that checks if the User-Agent header matches at least one of the patterns specified in “MUNCH.USER_AGENTS.CAB_PATTERN_*”. The Flame registry files that we have contained the following patterns:

MUNCH.USER_AGENTS.CAB_PATTERN_4 : WinHttp%-Autoproxy%-Service.*

MUNCH.USER_AGENTS.CAB_PATTERN_3 : Windows%-Update%-Agent.*

MUNCH.USER_AGENTS.CAB_PATTERN_2 : Industry Update.*

MUNCH.USER_AGENTS.CAB_PATTERN_1 : Microsoft SUS.*

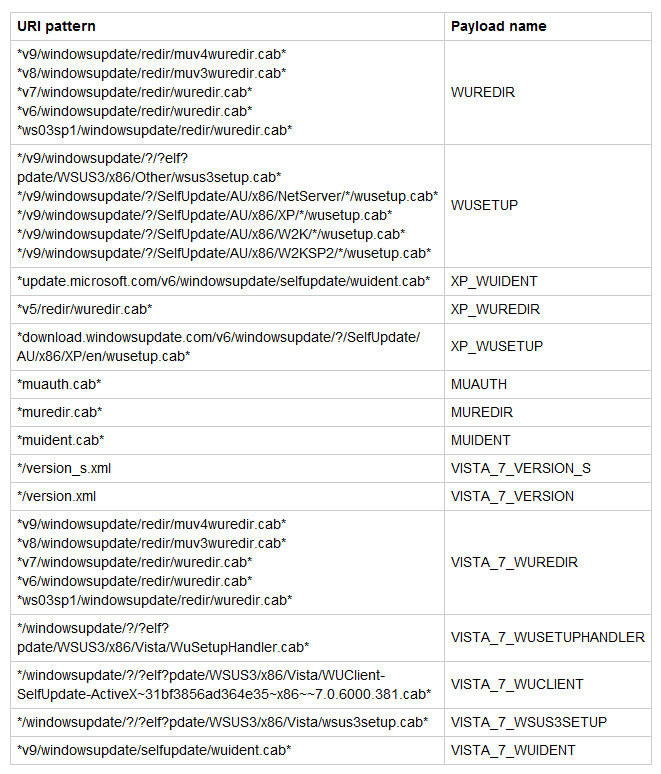

2) Checks if the requested URI matches any pattern specified in the list of strings called “MUNCH.GENERIC_BUFFERS.*.data.PATTERN”. If one of the expressions match, it then gets the buffer specified in the corresponding “MUNCH.GENERIC_BUFFERS.*.data.FILE_DATA” value, reads the payload value called “MUNCH.GENERIC_BUFFERS_CONTENT.value_of_FILE_DATA” and sends it to the client.

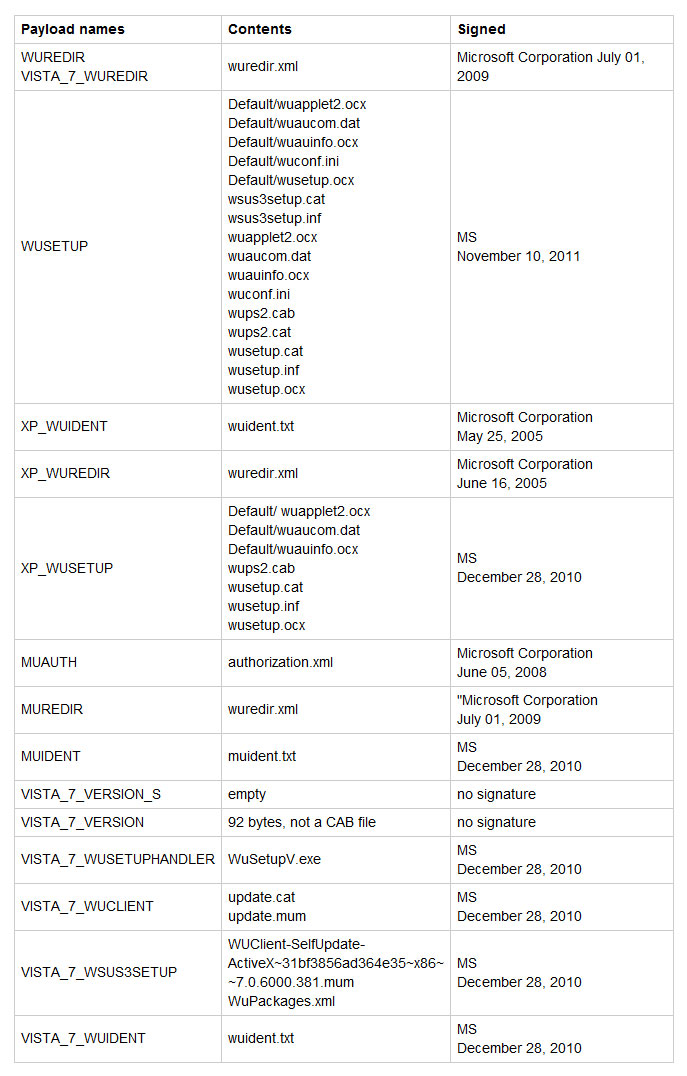

All the payloads are listed in the Flame’s registry with names starting with “MUNCH.GENERIC_BUFFERS_CONTENT.payload_name”, and are encoded with a fixed 104-byte RC4 key.

Most of the payloads are signed CAB archives. The archives that contain malicious code are signed by “MS” in Dec 2010 and Nov 2011 while other archives seem to originate from the genuine Windows Update service and are signed by “Microsoft Corporation”.

Since the CAB files have valid signatures (revoked by Microsoft at the moment), the Windows Update service receives and processes them as valid updates. They are downloaded and installed, effectively executing the malicious payload.

The main payload module within these CAB files is a downloader component called “Wusetup.ocx” or “WuSetupV.exe”. It collects general information about the computer, including time zone information, and tries to download “http://MSHOME-F3BE293C/view.php”, with host information appended to the request URI. Since the name “MSHOME-F3BE293C” is handled by the SNACK module, the URL points to the running MUNCH server that serves the main Flame module “mssecmgr.ocx” on this URI.

WuSetupV downloads the file, saves it to “%windir%Temp~ZFF042.tmp” on the target machine, loads it as a DLL and invokes its export “DDEnumCallback”, which is Flame’s installation routine. The new machine then becomes infected.

Better than zero-day

When we first discovered Flame, we started looking in its code for at least one exploit that used a zero-day vulnerability to spread Flame and infect other machines inside the network. Given its sophistication and the fact that it infected fully patched Windows 7 machines, there should have been one. What we’ve found now is better than any zero-day exploit. It actually looks more like a “god mode” cheat code – valid code signed by a keychain originating from Microsoft. The signature was discovered and immediately revoked by Microsoft, and a security advisory with update KB2718704 was promptly published.