A phishing campaign with a clever Spotify lure has been spotted trying to harvest user credentials for the popular streaming service.

Researchers at AppRiver detected the offensive earlier this month, in a campaign looking to compromise Spotify customers using bogus – but convincing – emails with the purpose of hijacking the owner’s account.

The emails attempt to dupe users into clicking on a phishing link that would redirect them to a deceptive website. Once at the site, users were prompted to enter their user name and password, where it would go directly into the bad guys’ repository of compromised things.

Obviously, the credentials could be useful if the victim has reused them on other, higher-value sites, like online banking. However, beyond selling the credentials on the Dark Web, “knowing just one password for a victim opens the door to a multitude of attack vectors,” David Pickett, cybersecurity analyst at AppRiver, told Threatpost.

“Knowing how someone creates a password offers a personal glimpse into their password creation mindset and probability of overall attack success,” he said. “This also gives an opportunity for social engineering using the same information which is important to the victim.”

For instance, the use of a term like Fluffy84 might tell an attacker that the victim loves their cat, and was potentially born in 1984 — along with the format they might use to create other passwords.

“That birthday information could be verified by online people data searches (Pipl, Wink, PeekYou, etc.) and lead to finding out all their animal names and important dates in their life,” he said. “Social-media platforms make this reconnaissance extremely simple and valuable.”

Also, the obtained information can easily be input into a password cracker to generate potential passwords for a hybrid password attack.

“This is using many unique password possibilities associated to the target from this gathered information specific to their life,” Pickett told us. “Their Spotify playlist might fit into the equation here if I found they enjoyed a particular artists or topic. Password-cracking software such as John the Ripper and Cain and Abel are popular utilities for these attacks, but there are many others.”

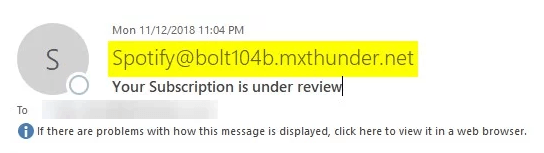

In this case, the email and phishing sites are both pretty convincing – but there are clues as to the danger that lurks behind them. For one, the “from” address of the email is clearly not legitimate, and neither is the URL, both with domains that are not related to the official spotify.com.

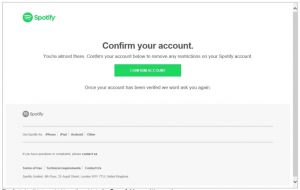

“The attacker has setup a well-disguised login page that looks identical to the actual Spotify login page,” AppRiver researchers said in a posting this week. “However, they can’t hide the actual URL in the web address browser.”

Also, if the user hovers with his or her mouse over the green button that says, “confirm account,” it’s possible to preview the URL, which will clearly not take the visitor to an official Spotify page.

While attacks like this that spoof legitimate services are extremely common to the point of being a daily occurrence, Pickett added that phishing emails can run the gamut in terms of sophistication – this one falls in the medium range.

“Many are a novelty, which are laughable, from attackers with very little skill; they still work against less-savvy users or they wouldn’t try them,” Pickett told Threatpost. “On the other end of the spectrum, there are attackers who have tremendous time and work involved with their knowledge, skills and experience being evident upon close inspection. These are typically APT level attacks being organized cybercriminal groups and state-sponsored attackers.”

He also said that the attackers with the most skill know and understand machine-learning algorithms, which might flag a cloned message from a legitimate service. The current Gozi/Ursnif/Dreambot malware attacks for instance currently do this by responding to previous legitimate conversations a user has had with a known contact.

“They develop their own attacks based on this technology,” he said. “It’s much more difficult to fake origination and message header information from a legitimate source, however, sender verification checks are routinely circumvented.”