A study by researchers at Carnegie Mellon University has concluded that Chinese social media sites are deleting messages with content that might be construed as controversial by the Communist Party – the first conclusive evidence that state censorship extends to social media sites like Sina Weibo, the popular micro blogging Web site that many have likened to a Chinese Twitter.

A study by researchers at Carnegie Mellon University has concluded that Chinese social media sites are deleting messages with content that might be construed as controversial by the Communist Party – the first conclusive evidence that state censorship extends to social media sites like Sina Weibo, the popular micro blogging Web site that many have likened to a Chinese Twitter.

The study, published on the Web site of First Monday, an online publication of the University of Illinois, Chicago, finds that censors in China delete around 16 percent of the messages submitted to Sina Weibo, the popular micro blogging Web site that many have likened to a Chinese version of Twitter.

The study, released in March, concludes that “soft censorship” in China – the removal of controversial subject matter from blogs and Web pages – is at least as popular as hard censorship, like the blocking of offensive sites. The result is suppression of news about events or individuals that are deemed threatening to the ruling Communist party.

The study is one of the most comprehensive attempts to quantify online censorship of social media within China. It was conducted by Noah A. Smith, an Associate Professor in the School of Computer Science at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU), along with two CMU graduate students: David Bamman and Brendan O’Connor.

Chinese government blocking of Western services like Twitter and Facebook make domestic services like Sina Weibo the best source of information about the extent of political censorship and the resultant social media behavior of users, the researchers wrote. In their study, they captured and analyzed 56 million messages from Sina Weibo, the Mainland’s microblogging site, between June and September, 2011. Researchers then sampled over a million of those 56 million messages after allowing three months to pass in order to detect evidence of soft censorship, such as individual messages or entire accounts that had been deleted from the service.

The results suggest that government censorship, though not total, is quite common. The researchers discovered that 212,583 of 1.3 million messages that were checked had been deleted from Sina Weibo – a bit more than 16 percent.

As part of their work, the CMU researchers developed a novel way of detecting “forbidden” terms. Rather than formulating a list of terms in advance, the researchers identified then monitored around 10,000 chinese language tweets on Twitter, which is not subject to Chinese government censorship. They then compared the incidence of certain terms that the researchers describe as “highly salient in real public discourse” by Chinese speaking people using services like Twitter and Sina Weibo.

In one example, researchers looked at posts on Sina Weibo concerning rumors about the death of Communist Party head Jiang Zemin in late June and early July, 2011. They found what they called a “striking pattern of deletion,” with 64 of 83 messages in their sample set containing Jiang’s name deleted (77 percent) on July 6, and 29 of 31 messages (93 percent) on July 7. Those numbers held up when researchers then combed over the entire corpus of 56 million Sina Weibo messages they harvested. Of the 33,363 messages found to contain at least one of the sensitive terms, 5,811 (or 17.4 percent) had been deleted.

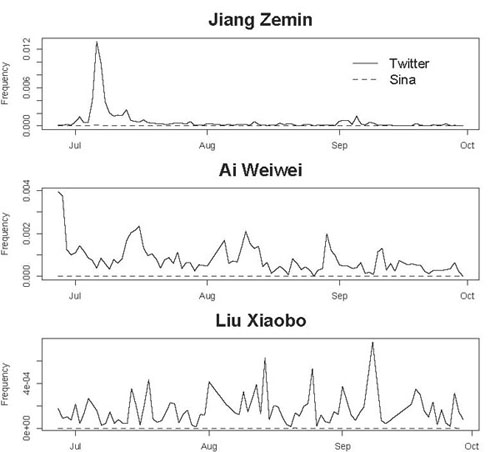

The researchers also examined the frequency of appearance of banned terms like “Jiang Zemin,” “Ai Weiwei” (artist and political activist) and “Liu Xiaobo” (political activist and Nobel Prize winner) on Sina and Twitter. They found that all the terms appear several orders of magnitude more frequently on Twitter than they do on Sina Weibo.

The use of soft censorship such as message deletion allows the government to enforce its ban on what it considers politically volatile speech, without overtly blocking attempts by citizens to broach sensitive topics online, researchers said.

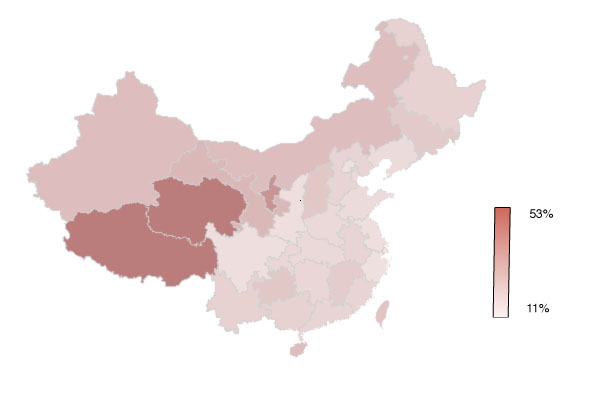

And, although Chinese censorship is portrayed monolithically in the Western media, the researchers found that censorship is not uniform across the Mainland. The rate of posts that are deleted in provinces in the far west and north of China, such as Tibet and Qinghai, have much higher rates of deletion (53 percent) than in eastern provinces and cities (around 12 percent), the researchers found. Furthermore, as the deletion rate suggests, Chinese censorship is not foolproof: many messages expressing opinions that run counter to Chinese government positions were not deleted, suggesting an element of randomness to the censorship that does occur.

The researchers concluded that the anecdotal reports of government censorship of social media are accurate. “There exists a certain set of terms whose presence in a message leads to a higher likelihood for that message’s deletion,” they said.