Two recently-patched flaws in Twitter’s platform have reignited concerns about user data-privacy issues.

On Monday, the social-media giant revealed a hole that accidentally enabled bad actors to pull the country codes of accounts’ phone numbers – and revealed that several IP addresses located in China and Saudi Arabia may have been trying to access the exposed data. This comes on the heels of a tricky glitch, disclosed over the weekend, that had allowed several apps to read users’ direct messages – even when they told users that they wouldn’t.

Like other social-media platforms, Twitter has come under scrutiny for how it collects and protects data. In May, a bug caused account passwords to be stored in plain text on an internal log; and in September, a flaw was disclosed that enabled software developers to read users’ private direct messages.

Researcher Terence Eden, who reported one of the new bugs via Twitter’s bug bounty program and was awarded $3,000 for his efforts, told Threatpost that regulatory efforts and heightened concerns around social-media data privacy is leading companies to make some changes.

“GDPR means that companies are finally starting to take user privacy seriously,” he told Threatpost. “The complexity of social apps – and the large amount of legacy code / endpoints – means there are often unexpected ways that your personal data gets leaked.”

Support Form Issue

Twitter in a Monday post revealed that an issue in one of its support forms could be used to discover the country code of users’ phone numbers associated with their Twitter account.

Twitter said while investigating the bug, it noticed some unusual activity involving the affected customer support form API: “Specifically, we observed a large number of inquiries coming from individual IP addresses located in China and Saudi Arabia,” according to Twitter. ” While we cannot confirm intent or attribution for certain, it is possible that some of these IP addresses may have ties to state-sponsored actors.”

The exposed support form was used by account holders to contact Twitter about issues with their account. The issue was fixed Nov. 16, according to Twitter.

The flaw could also allow bad actors to discover whether a users’ account had been locked by Twitter. Accounts are locked if they appear to be compromised or in violation of the Twitter rules or terms of service.

“Importantly, this issue did not expose full phone numbers or any other personal data,” Twitter said in a post about the incident. “We have directly informed the people we identified as being affected. We are providing this broader notice as it is possible that other account holders we cannot identify were potentially impacted.”

0Auth Permissions Flaw

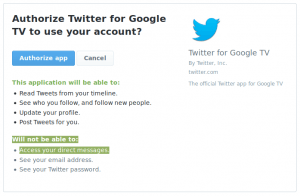

In another blow to Twitter’s data protection efforts, Eden on Dec. 14 said he had discovered a bug that could allow apps to access users’ DMs – even when they said they would not in the “permissions” breakdown.

“For some reason, Twitter’s OAuth screen says that these apps do not have access to direct messages,” said Eden in a post about the flaw. “But they do! In short, users could be tricked into allowing access to their DMs.”

The issue stems back to 2013, when the OAuth keys that official Twitter applications use to access users’ Twitter accounts were leaked. That means that unapproved third-party applications could use the keys to impersonate legitimate third-party apps and circumvent any access control measures Twitter has in place for unofficial apps.

To act as a safeguard from third-party apps taking these keys and using them to send users to their app, Twitter put in “callback address restrictions.” These restrictions make apps prompt users to go to their app use a predefined URL. That means when a user signs in to an app using their Twitter account, a callback URLs provides directions on where a user should go after signing in with their Twitter credentials.

However, Eden noted, the issue is that not every app has a URL. Apps that aren’t approved by Twitter instead use a PIN as an authorization mechanism, but the PIN apps don’t display the correct 0Auth information to the user. That means that users could be tricked into clicking an “authorize app” page that doesn’t list access to DMs as a permission – even though the app does have those permissions.

Eden told Threatpost that using the proof of concept, he was able to read his own DMs, and those of a dummy account he had created.

“This would have been a difficult attack to exploit,” Eden told Threatpost. “An attacker would have had to convince you to click on a link, sign in, then type a PIN back into the original app. Given that most apps request DM access – and that most people don’t read warning screens – it is unlikely that anyone was mislead by it.”

Twitter for its part said it does not believe anyone was mislead by the permissions that the applications had or that any users’ data was unintentionally accessed by applications: “To our knowledge, there was not a breach of anyone’s information due to this issue,” the social media company said in the HackerOne briefing. “There are no actions people need to take at this time.”