Users heed Web browser security warnings more than previously thought, according to research unveiled this week.

The research is part of first in-depth large-scale field study of browser security warnings, according to Devdatta Akhawe of the University of California, Berkeley and Adrienne Porter Felt, a research scientist with Google.

The paper, “Alice in Warningland: A Large-Scale Field Study of Browser Security Warning Effectiveness,” (.PDF) was published this week in advance of a technical session the two plan to present at USENIX’s Security Symposium next month in Washington, D.C.

More than 25 million warning screens on Google Chrome and Mozilla Firefox were analyzed over the course of two months, from May to June 2013. Since it focused on user interaction, this particular study focused on bypassable browser warnings, warnings where users are given the option to either “proceed anyway” (Chrome) or choose that they “understood the risks” (Firefox) to make their way to the suspicious site in question.

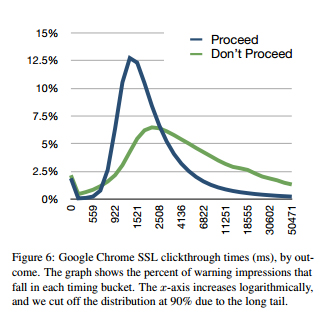

By implementing metrics in browsers to count the times a user saw either a malware, phishing or SSL warning, Akhawe and Felt were able to measure users’ clickthrough rates for each.

On the whole, users pay attention to the warnings they see.

Users clicked through, essentially ignoring or disregarding a potential problem, fewer than 25 percent of the malware and phishing warnings they saw on both browsers, and one-third of SSL warnings on Firefox.

There was the anomaly though – as many as 70 percent of users blasted through SSL warnings on Google Chrome, more than twice as many people than clicked through a similar warning on Firefox, a statistic that suggests Google’s warning could use some refining.

There was the anomaly though – as many as 70 percent of users blasted through SSL warnings on Google Chrome, more than twice as many people than clicked through a similar warning on Firefox, a statistic that suggests Google’s warning could use some refining.

The study notes that Google’s warning requires a user click only once to bypass the security page while Firefox’s requires a user to click three times, but argues that a combination of variables could explain the difference in clickthrough rates. Mozilla’s warning features a “a policeman and uses the word ‘untrusted’ in the title,” which likely deters users from clicking. Firefox users can also permanently store exceptions to automatically bypass future security warnings, which could also account for it having a lower clickthrough rate than Google.

Google Chrome users either aren’t “heeding valid warnings or the browser is annoying users with invalid warnings and possibly causing warning fatigue,” the researchers explain in the paper, calling the high clickthrough rate “undesirable.”

Felt, who works at Google notes the company has begun testing its SSL warnings in order to improve how it impacts users and may experiment with an “exception-remembering” feature in the future.

Google SSL warning numbers aside, the mostly positive statistics should encourage a wider implementation of browser warnings going forward. As users’ experiences with the warnings directly relates to their effectiveness, the researchers argue they’re worth following.

“Security warnings can be effective in practice; security experts and system architects should not dismiss the goal of communicating security information to end users.”