When Android phone manufacturers tweak devices and customize phones with special software, apps and code, it has a direct effect on the security of each device. In some cases, the changes made can account for more than 60 percent of vulnerabilities found in devices.

That’s according to a paper “The Impact of Vendor Customizations of Android Security,” (.PDF) recently published by a group of computer science students at North Carolina State University with the help of Android researcher and NC State professor Xuxian Jiang.

The research is set to be presented at the 20th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security in Berlin later today.

In the study, researchers looked at 10 different Android smartphones (HTC One X, Galaxy Nexus S3, etc.) from five different vendors, two per vendor, one per generation (pre-2012 2.x build and post-2012 4.x build) and examined the security flaws that stemmed from each device’s customized setups.

Using a tool called the Security Evaluation Framework for Android (SEFA), the researchers looked at thousands of lines of code to determine each preloaded app’s provenance (who authored it), permission usage (how many permissions each app has) and its vulnerability distribution (could the app be compromised). The SEFA tool, developed by the researchers, basically looks at a phone’s firmware, compares it to Android’s stock Android Open Source Project (AOSP) code and helps detects vulnerabilities in apps.

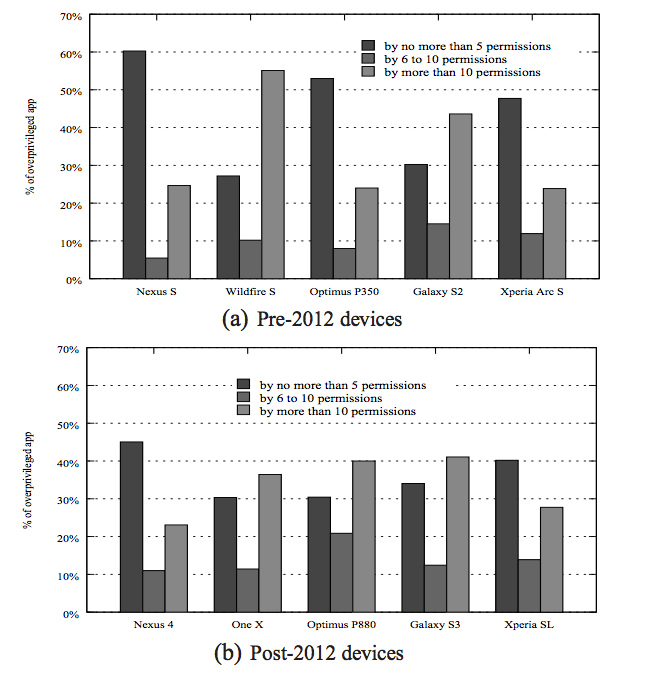

Eighty-two percent of the apps scanned came customized by the vendor and 86 percent of those apps wound up being what the researchers called overprivileged, meaning they “unnecessarily request more Android permissions than they actually use.”

While plenty of apps leverage user permissions, the quintet’s research also looked for legitimate “real, actionable exploits” in phones. Between 65 percent and 85 percent of the vulnerabilities found on LG, Samsung and HTC phones came as a direct result of the vendors’ customizations. The group found a handful of broken security-critical permissions in apps that can send SMS messages on behalf of the user without their permission and divulge personal information.

For example, the researchers found a preloaded app in Samsung’s Galaxy S3 phone called Keystrong_misc. If compromised it can lead to a series of reflection attacks and go down a “dangerous path for performing a factory reset, thus erasing all user data on the device.”

Vulnerabilities in the LG Optimus P880, another phone the researchers analyzed could lead to a device reboot and expose access to several mailbox tables.

Xuxian and his students claim they attempted to contact the corresponding phone vendors and while some have confirmed the vulnerabilities others have still not spoken to them “after several months,” according to the paper.

Perhaps the most troubling trend in the study and something that may beckon a change in the way vendors pre-load their devices in the future is that there really wasn’t much of a difference in the amount of vulnerabilities from one generation of phones to the next.

Perhaps the most troubling trend in the study and something that may beckon a change in the way vendors pre-load their devices in the future is that there really wasn’t much of a difference in the amount of vulnerabilities from one generation of phones to the next.

“Vendor apps consistently exhibited permission overprivilege, regardless of generation,” reads one part of the paper.

While technically the number of vulnerabilities and overprivileged apps (see right) decreased from pre-2012 phones to post-2012 phones, patterns were stable over time, suggesting “the need for heightened focus on security by the smartphone industry,” according to Xuxian and company.

The problem is since Android is such a massively popular open source platform, Google makes it, distributes it as the AOSP and manufacturers and carriers are free to tweak it as they see fit. This leads to a completely varied product complete with third-party apps and meaningless bloatware that in the end resembles a splintered version of the original software.