The 2015 Verizon Data Breach Investigations Report (DBIR) did some mythbusting on two fronts: the estimated cost per record lost in a breach is much lower than reported elsewhere; and mobile malware is a no-go.

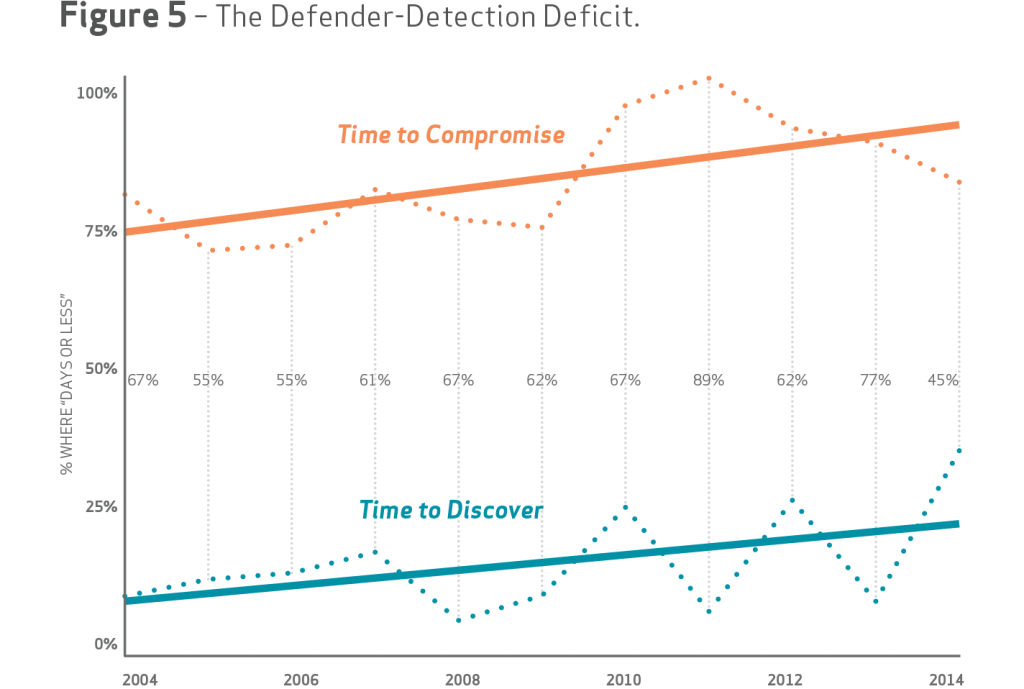

The DBIR is Verizon’s annual data dump collected from breaches it has investigated, along with contributed data from 70 of its partners. Now in its eighth iteration, the data points continue to trend in favor of attackers, who continue to be much quicker at finding and exploiting vulnerabilities than defenders are at discovering attackers on their systems and cutting them off. In close to 80 percent of incidents (the 2015 DBIR covers 79,790 incidents and 2,122 confirmed breaches), attackers’ time to compromise was days or hours, while only close to 35 percent of breaches were detected by defenders in the same time frame.

But the real eye-opening numbers are around data breach costs to an affected enterprise or SMB, the first time Verizon has ventured into putting a solid number on the cost of a breach.

“People have for years tried to get us to talk about the impact of breaches, but we just haven’t had the data,” said Jay Jacobs, a Verizon data scientist and one of the report coauthors. Jacobs said one partner, Net Diligence, contributed cyber liability insurance claim data from its partner network of cyber insurance carriers. “This is what people are claiming they lost; it’s a very objective data set to work with.”

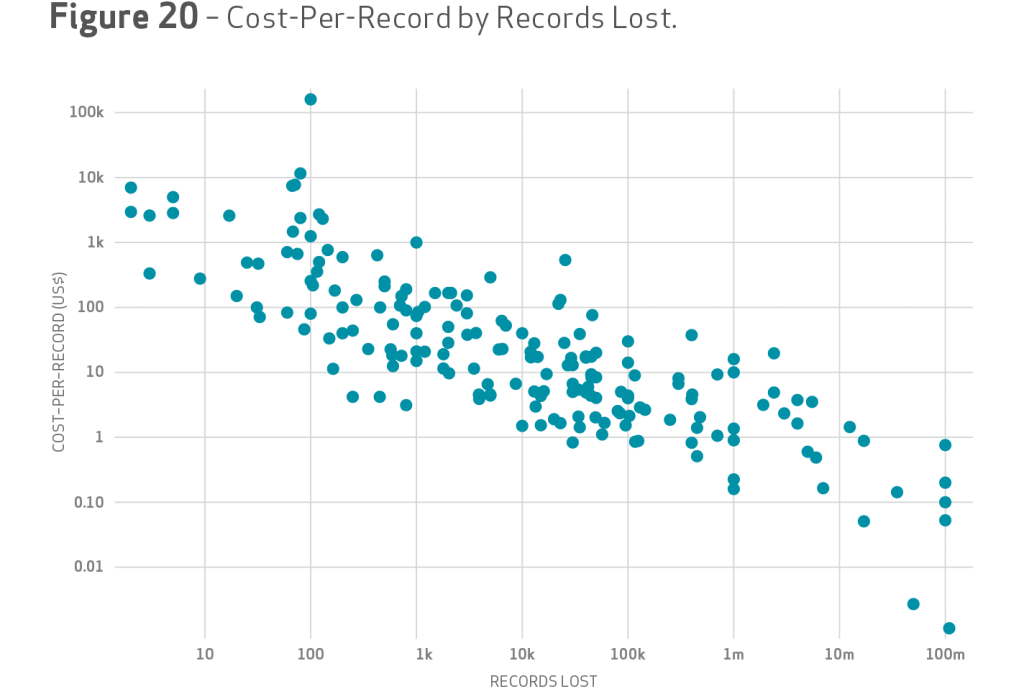

The data set of 191 claims with loss of payment card information, customer personal information and medical records was the basis for a fresh look at data breach cost impact. The result was a string of new conclusions that cast doubt onto older models that derive a cost-per-record by dividing the sum of loss estimates by the total number of records lost. The annual Ponemon Institute Cost of a Data Breach study, for example, puts that number at $201 per lost record in 2014. Applying that same formula to Verizon’s numbers of $400 million in estimated losses divided by 700 million compromised records puts the cost-per-record at 58 cents.

“The 58 cents number is an example of why we don’t want to focus on numbers like that,” Jacobs said.

The uncertainty between the two numbers forced Verizon to try its luck at developing another model that is explained in the report in great details. The new model determined that in mega breaches such as Target or Home Depot where tens of millions of records were lost, the average cost per record was in the pennies, as opposed to smaller breaches where the average cost per record could be astronomical, Jacobs said.

“Speaking personally, the costs were lower than expected,” Jacobs said. “Look at Target: initial estimates put that at billions in losses, and we’re just not seeing that.”

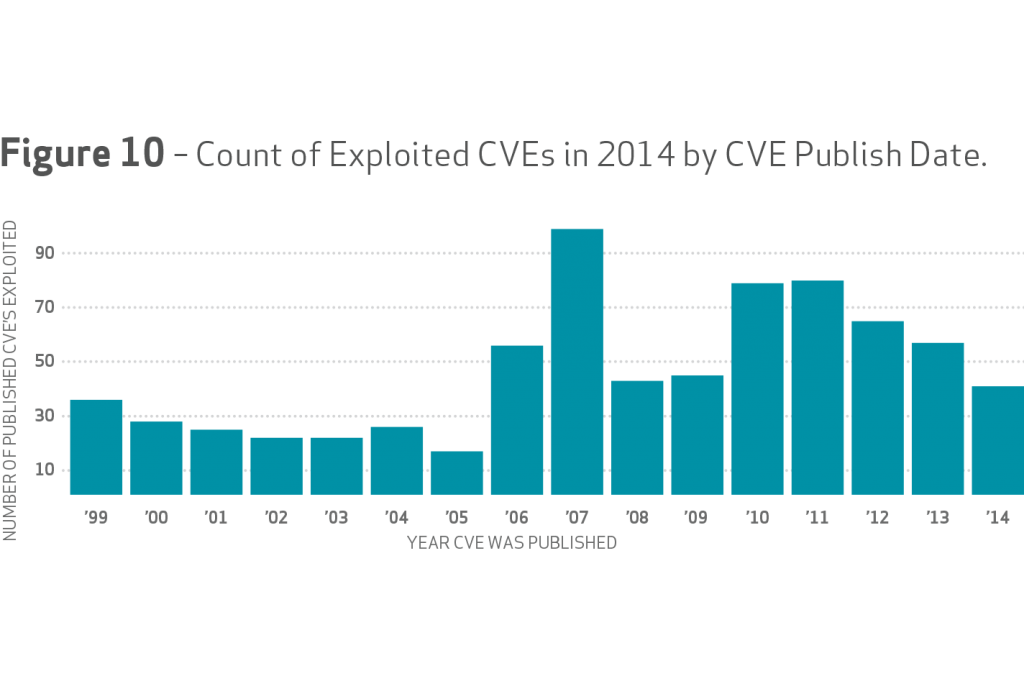

As with previous versions of the DBIR, smaller retailers, hospitality providers and other smaller service providers continue to be hammered by attackers, who are taking advantage of lax patching and vulnerability management to exploit weaknesses in payment card systems and point of sale systems. For example, the DBIR said that 99.9 percent of exploited vulnerabilities had been compromised more than a year after a CVE was published and patched. Older vulnerabilities, some going back to 1999, were exploited in breaches in 2014, with a steady diet of CVEs from 2007, 2010 and 2011 at the forefront of breaches.

“We’re seeing a tremendous amount of old and moldy vulnerabilities that are still out there and are not being addressed, patched or remediated any way,” said Marc Spitler, a Verizon senior analyst and DBIR coauthor. “We expected to see some, but we thought they’d be outliers, rather than front and center.”

Another thing that wasn’t front and center was mobile malware.

Breaches in 2014 were shy of compromised mobile devices; almost no iOS malware was detected while 0.03 percent of Android devices were impacted by malware that steals data or joins the device to a botnet.

“We did see a lot of adware, annoying type of software, but once we filtered out the annoying stuff, there was a small proportion out there,” Jacobs said. “We’ve certainly got a lot of evidence that mobile platforms are vulnerable.”

And that presents an opportunity, Jacobs said.

“It confirms what folks in the field are saying and puts to rest that vulnerabilities mean more than actual exploits; exploits are not happening,” Jacobs said. “We’re not saying that mobile should be ignored by organizations, but the message is that they have an opportunity to get ahead of attackers. Start getting visibility and control, and administrate in a way they’ve never had such an opportunity before.”