Researchers at Kaspersky Lab, domain registrar GoDaddy and OpenDNS have taken steps to cut off Internet access for machines infected with the Flame worm. In the process, the researchers say they uncovered a large and complex command and control infrastructure of more than 80 Web domains and collected clues that put the origins of Flame as early as 2008.

Researchers at Kaspersky Lab, domain registrar GoDaddy and OpenDNS have taken steps to cut off Internet access for machines infected with the Flame worm. In the process, the researchers say they uncovered a large and complex command and control infrastructure of more than 80 Web domains and collected clues that put the origins of Flame as early as 2008.

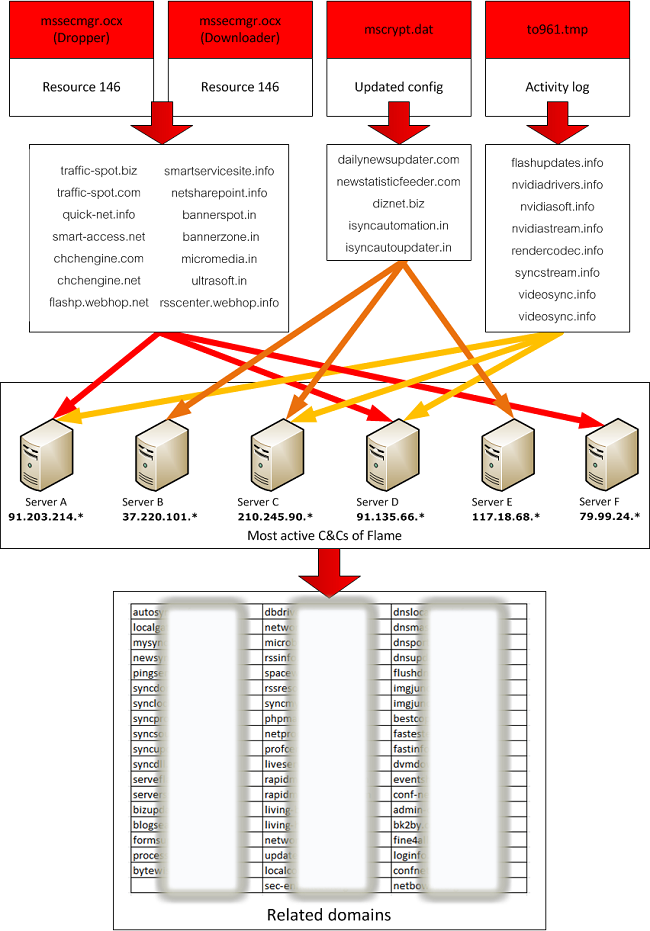

Evidence collected from a close analysis of the mysterious malware suggests that Flame is more than three years old and has relied on a huge network of more than 80 command and control Web domains to continue receiving orders from those behind the cyber espionage toolkit, according to posts on Kaspersky Lab’s research blog, Securelist, and OpenDNS.com.

The analysis pointed out significant differences between Flame and earlier, APT-style threats like Stuxnet and Duqu, Kaspersky analyst Aleks Gostev wrote on Monday. For example, while Duqu’s authors took extraordinary steps to conceal the source of its central command and control server and scripts, Flame’s authors were far less careful: dropping control scripts on the dozens of command and control servers that the malware was programmed to consult.

“The Duqu attackers were a lot more careful about hiding their activities compared to the Flame operators,” Gostev wrote.

Flame’s authors also purchased and registered their own Web domains, rather than piggybacking their command and control malware on already-compromised domains, as the Duqu authors did. Flame domains were registered by unknown attackers using fake identities like “Adrien Leroy,” “Ivan Blix” and “Maria Weber.” Many of the identities were given fake addresses in Germany and Austria, with a big concentration of fake addresses in the Austrian city of Vienna, Gostev wrote.

The decision to register “clean” domains for Flame to use allowed researchers to pin down the beginning of the Flame campaign to 2008, said Dan Hubbard of OpenDNS.org. “These domains were not associated with anything prior to being used by (Flame),” he told Threatpost. “This is the long tail of the Web.”

Using clean domains for command and control had clear advantages and may have provided clues to the malware’s origins, but it also had advantages for the attackers, Hubbard said. Because the domains were not infected with other malware or associated with malicious activity, they were unlikely to raise flags from antivirus- or Web filtering software at the target organizations, he said.

The groups have succeeded in redirecting requests from infected systems to a DNS “sinkhole” – IP addresses not affiliated with the Flame malware, Hubbard said.

In the meantime, the data collected from the Flame systems and from Kaspersky and GoDaddy suggests that the number of systems actually infected with the worm is almost vanishingly small. Hubbard said the daily traffic from Flame systems is “very low… around 300 to 400 requests per day.” Data from the Kaspersky Security Network (KSN) supports that assertion. KSN statistics find just 359 infected systems in the top five most infected countries: Iran (185), Israel and Palestine (95), Sudan (32), Syria (29) and Lebanon (18). Even those numbers may overstate the size of the Flame problem, said Hubbard. Around a quarter of the traffic OpenDNS now records related to Flame is from fellow security researchers, he said.