MONTREAL — While troll farms, influence campaigns and Twitter bots that spread disinformation have all become high-profile and negative aspects of the social-media universe, new research shows that there is actually a rich and complex supply chain behind these efforts.

“Social-media fraud is widespread and we know this – what we didn’t know was just how many players are actually involved in it,” explained Masarah Paquet-Clouston, a researcher with GoSecure, speaking at Virus Bulletin 2018 here on Thursday.

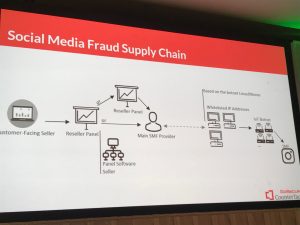

Customer-facing websites that claim to be legitimate businesses, such as Devumi, market the ability to “quickly gain followers, viewers, likes and more” through vaguely defined “marketing tactics.” But behind the scenes, the researcher said, lies a complex chain of traffic resellers, platform providers and bot traffic – an apparatus that fuels the business of inflating social-media traffic as well as more nefarious activities such as influence campaigns.

Bot Traffic

The string that unraveled the sweater on this ecosystem started with the Linux/Moose botnet, first spotted in 2015.

Linux/Moose is an IoT botnet, which, as its name suggests, infects devices that have embedded Linux systems. Like Mirai and other IoT botnets, it displays a wormlike behavior, spreading by brute-forcing Telnet credentials. But instead of its traffic being marshalled to drive denial-of-service campaigns, it uses enslaved devices as proxies to relay traffic to social media sites. It steals HTTP cookies on social media sites and performs a type of click-fraud that is used to accumulate illegitimate views, create fake followers and generate Likes. About 86 percent of its traffic flows to Instagram, GoSecure found.

Looking further into Linux/Moose’s infrastructure, Paquet-Clouston found that the botnet’s architecture includes a whitelist of seven IP addresses that can push traffic through those proxies. After analyzing the traffic fingerprints left by each IP address on Linux/Moose-infected systems, the researcher eventually determined that these IP addresses are Windows servers with proxy-aware Instagram clients, used to manage fake social-media accounts that perform the faux Likes and follows.

In a savvy move, each IP address is tied to a specific group of fake accounts with no overlap between them – which is a usage pattern that is more credible when it comes to Instagram’s algorithm for rooting out fraud than bouncing between IP addresses.

After decrypting and analyzing the traffic for these IPs, Paquet-Clouston found similarities between all seven in terms of their TLS fingerprints, geography, websites targeted, user-agents and so on – leading her to conclude that they’re all controlled by the same actor.

Bulk Traffic Resellers and Software Panels

It was during the whitelist analysis that Paquet-Clouston uncovered evidence of bulk reseller panels that sell traffic to the aforementioned customer-facing websites (which as mentioned, in turn sell followers, traffic and likes to end users as legitimate businesses).

“You would see an Instagram or Twitter account advertising bulk traffic resellers, where people can buy wholesale followers and likes,” she explained, adding that they all had similar login pages, with different customized branding and pictures. “When we visited these reseller sites – 343 panels found in all – they all seemed really similar, so I began wondering if the same actor was behind all of them.”

However, the rabbit hole went still deeper. Further exploration yielded thousands of these type reseller sites, all similar in form.

“Could it really be the same actor behind all of these panels?” Paquet-Clouston said. “Surely not – five or 10 maybe, but thousands is a lot.”

After some analysis of the specific traits in the reseller sites, she found that certain clusters of them seemed related and built on the same platform. For instance, out of 486 reseller panel websites spotted in action on July 17, 99 percent of them were using the same reCAPTCHA SiteKey. This raised the possibility that there was another player in the supply chain: A platform provider, a.k.a. a software panel seller, that enables people to easily these kinds of build bulk resale sites.

“The reCAPTCHA link tying all those sites together tells us that they are all tied to one software panel seller,” she noted.

This hypothesis was confirmed by digging deeper – the researcher uncovered an ad for a software panel that offered an “all-in-one solution for reselling or providing social media management services,” including web hosting and panel maintenance. As such, these software panels seller makes it very easy to get started in the social-media fraud business, Paquet-Clouston added.

“Even with no technical skills, a person can enter this market no problem,” the researcher explained. “The platform is an all-in-one service – all you need is a domain name, and they do everything else.”

Cost to use the software panel ranges from $50 to $100 per month.

In all, GoSecure found 1,500 bulk traffic reseller sites, enabled by just five software-panel sellers.

Connection to Botnets?

The next step was figuring out how these reseller panels connect to Linux/Moose or other IoT botnets to capture their traffic. It is likely that most of the traffic that ends up being sold by customer-facing websites is generated by bots.

However, Paquet-Clouston said more investigation is needed. The software platforms used by the bulk traffic resellers contain APIs for onboarding traffic from external sources – these sources could be a troll farm, the reseller’s own botnet, another reseller or a botnet that’s already generating large amounts of social-media traffic, like Linux/Moose.

She ran into a snag, however. The Linux/Moose botnet doesn’t allow for API connections to its whitelisted IP addresses — they only accept remote desktop protocol (RDP) connections. That left the researcher wondering how the botnet could be connected to these reseller panels.

Paquet-Clouston came up with two hypotheses: “One, the whitelisted IP addresses’ fat client fetches orders by itself; or, an RDP tunnel is created between the reseller and the whitelisted IP address servers,” she explained. The first case hinges on the a sophisticated proxy-aware Instagram fat-client that the botnet uses to manage fake accounts and the flows of interaction with Instagram. Because it has rich functionality, it’s possible that this is brokering the traffic exchange as a separate process. Otherwise, a manual RDP connection could be made between reseller and botnet.

As it stands, “we still have not [definitively] found out how resellers…are linked to Linux/Moose’s whitelisted IP addresses,” she said. “We know they are related, since some social-media fraud reseller panels were found in the Instagram accounts followed by Linux/Moose’s traffic.”

The Full Supply Chain

Even with outstanding questions, taken together, a picture emerges of the full supply chain. Put simply, customer-facing marketers like Devumi (along with more shadowy players involved in trolling and other forms of social-media fraud) buy traffic from bulk traffic resellers, which are enabled by a software-panel reseller. These bulk traffic resellers in turn very likely connect to whitelisted IP addresses associated with Linux/Moose or a similar botnet in order to take in their traffic.

While certain details still need to be cleared up, it’s certain that this is a sprawling enterprise involving hundreds of players. The upshot though is that it’s not nearly as profitable for everyone concerned as researchers expected it to be. GoSecure research found that traffic resellers with customer-facing websites charge a median price of $13 for 1,000 “followers” on Instagram. A reseller panel meanwhile makes just $1 from those 1,000 fake followers.

“We really thought this would be making a lot of money,” Paquet-Clouston said. “But it turns out that even owners of reseller panels have a hard time being profitable. The actors are just not making as much as if they set up a legal business, and they have the added hassle of having to hide behind all of these other people.”

For the organizations, minor celebrities and ordinary people that buy this kind of traffic, the story doesn’t have much of a happy ending either. The research shows that about 80 percent of faux followers are gone within four months, because they get flagged as spam or fakes – meaning that people are in a constant scramble to maintain their artificially inflated social-media presence.

However, the one big winner is the customer-facing traffic seller group. GoSecure found that someone looking to beef up their social-media presence would pay around $112 for 10,000 follows. The Demuvis of the world in turn keep about 92 percent of that revenue.

“Further research is required to better understand the dynamics that link each actor in the supply chain,” Paquet-Clouston said. “Still, this research is part of a two-year-long investigation that attempts to place a botnet’s operation into its economic context.”