Yik Yak, an application that allows users to share purportedly anonymous status updates with others near them, has fixed a critical vulnerability in its iOS app that could have de-anonymized users and let attackers take total control of someone’s account.

Yik Yak’s security team was apparently notified of the vulnerability last Tuesday and pushed a new build, 2.1.3, to address it on iOS the following day.

The app’s main problem stemmed from Flurry, a Yahoo-owned, third party advertising and analytics tool that Yik Yak uses to keep track of users and serve up customized ads. While Yik Yak, like any formidable app should, encrypts user information and sends it over HTTPS, Flurry, by default, disables HTTPS.

According to Sanford Moskowitz, an intern at the cloud security firm SilverSky Labs, that wasn’t the only issue with the app. Since Yik Yak – which is sort of an amalgam of Twitter and GPS – is based on anonymity, there are no passwords, which means that the only way to identify users is via their user ID, a string of characters that associates users with the app.

Moskowitz described his research in a blog post, ‘Yak Hak: Smashing the Yak,” last week.

“If you can find their ID, you have completely compromised the user and you’ll be able to view all their ‘private’ posts,” he warned.

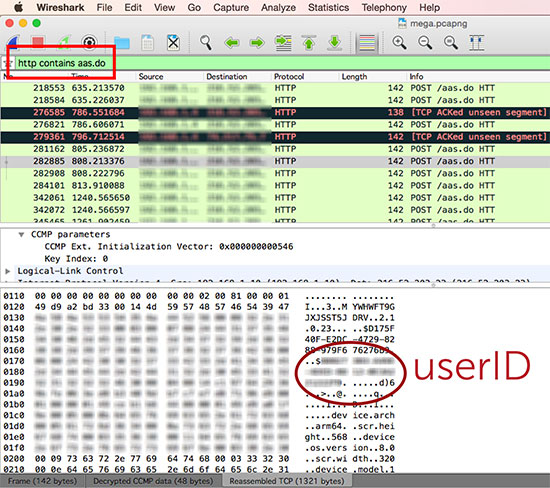

This is because, according to Moskowitz, Yik Yak sends Flurry the user ID over plaintext HTTP, a protocol that could be easily sniffed if both the user and attacker are on the same WiFi network.

Moskowitz gives an in depth description of how to do that on his blog, but it involves capturing traffic with Wireshark, a popular (and free) packet analyzer. While users can use the tool’s settings to sniff out users themselves, Moskowitz also provides a script in his blog post that can filter through packets of information on its own and point out anyone on the network using the app.

Moskowitz even tips would-be sniffers off on the best way to de-anonymize users after they’ve gleaned an ID.

After they’ve determined someone’s ID, with a toolkit he’s made public and a jailbroken iPhone, anyone could easily “take complete control over” an account, he claims.

Moskowitz, a computer science major at New York University, points out that a similar issue exists in the Android version of the app that enables the viewing of communication between the app and its server in plaintext. While the Android version also received an update, complete with “bug squishing,” last Wednesday, it’s unclear whether or not it addressed the bugs Moskowitz is referring to.

Email inquiries to the app’s support team were not returned on Tuesday.

Launched in late 2013, the app has garnered its fair share of criticism over the last year or so, namely from parents and teachers who claim that its led to instances of bullying in some circles. Yik Yak has attempted to combat those worries by blocking access to the app in predefined geographic areas where there are high schools but that hasn’t stopped dozens of students from getting arrested for making threats via the service.

As should be expected, the app has both a lengthy terms of service and privacy policy that make it clear that submissions made to the service are done on a “non-proprietary and non-confidential basis,”something that suggests that information shared with the app may not be as anonymous as its billed.

“The internet is scary,” Moskowitz states at the end of his writeup, “Consider keeping private thoughts to yourself.”