Cybercriminals behind the Tinba banking Trojan have been homing in on some of the larger banks in Russia and Japan, experts claim.

According to researchers with Dell SecureWorks, who looked at an instance of the malware last month, configuration files in one variant are targeting one of the “biggest banks in Europe,” along with two popular Russian payment service providers.

Like other banking Trojans on the market, Tinba is mostly used to pilfer banking credentials, passwords, and other information that’s later used to perpetrate wire, or Automated Clearing House (ACH) fraud. It’s called Tinba or ‘Tiny Banker’ because the code behind it is so small, often as little as 20 kilobytes.

When SecureWorks researchers checked on the malware in October, they found 655 registered domains, 62 unique request paths and 43 unique encryption keys, statistics that’s led them to believe there’s now more than a dozen groups running Tinba 2.0 botnets.

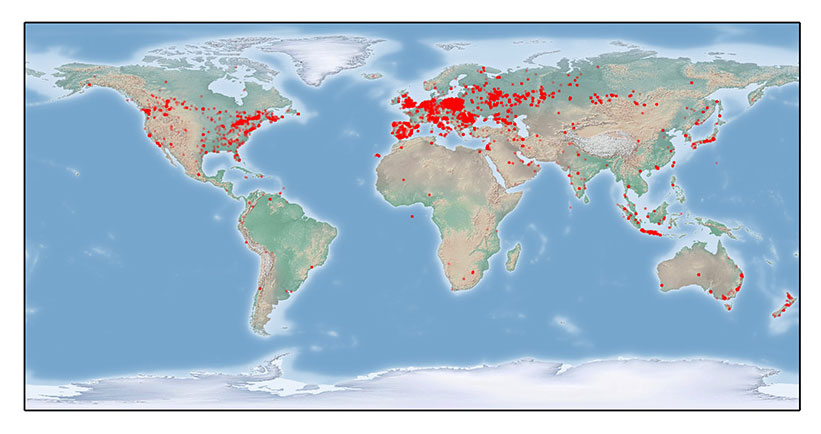

To get a sample of how far the malware has spread lately, researchers sinkholed a few of the botnets and found infections from 32,805 IP addresses, the bulk of which, 34.5 percent, were located in Russia. A healthy dose of the infections were also clustered around Europe. 22 percent were in Poland, while Spain, Germany, and the United Kingdom were also popular targets, according to a map the group released Tuesday:

Researchers with IBM observed a Tinba campaign targeting Poland, Italy, the Netherlands, and Germany earlier this year, but this is the first time the malware’s been spotted going after Russians, something the researchers claim is something of a rarity.

SecureWorks researchers claim that malware like Tinba infrequently targets Russian computers, acknowledging the country is often a hub for the creation of “pervasive banking Trojans and other money-making malware.”

“There definitely seemed to be a propensity on the part of the cyber criminals behind these operations not to compromise Eastern European and Russian computers,” the researchers write.

In addition to Russia and Europe, researchers claim they’ve also seen an uptick in Tinba attacks that target Shinkin banks, or cooperative financial institutions, located in Japan, along with other Asian countries like Indonesia and Malaysia.

The source code for Tinba first began to make the rounds in July 2014 after it was posted on an underground forum, but that was the first iteration of the malware, a version that’s apparently quite different from 2.0.

According to SecureWorks, the latest version of the malware appears to be controlled by one threat group and is primarily spread through spam email and exploit kits like Neutrino, Angler, and Nuclear. The malware is multi-faceted, comes complete with a list of domain names, RSA keys, and request paths, and has led to tens of thousands of active malware infections

2.0 also uses a more sophisticated domain generation algorithm, which makes it mitigation tougher. The most recent version uses four hard-coded TLDs (top level domains) instead of one, to generate 400 possible domains, instead of 1,000. The malware also has a RSA signature mechanism that verifies whether or not the command and controller it communicates with is legitimate.

“The command-and-control communications rely on a domain generation algorithm (DGA) and verify the legitimacy of the server through RSA cryptography, making Tinba 2.0 botnets more challenging to disrupt,” Dr. Brett Stone-Gross, a Senior Security Researcher with the group said, “As a result, CTU researchers expect Tinba 2.0 to continue to remain popular in the foreseeable future.”