Google said that up to 1 million Gmail users were victimized by yesterday’s Google Docs phishing scam that spread quickly for a short period of time.

In a statement, Google said that fewer than 0.1 percent of Gmail users were affected; as of last February, Google said it had one billion active Gmail users.

Google took measures to protect its users by disabling offending accounts, and removing phony pages and malicious applications involved in the attacks. Other security measures were pushed out in updates to Gmail, Safe Browsing and other in-house systems.

“We were able to stop the campaign within approximately one hour,” a Google spokesperson said in a statement. “While contact information was accessed and used by the campaign, our investigations show that no other data was exposed. There’s no further action users need to take regarding this event.”

The messages were a convincing mix of social engineering and abuse of users’ trust in the convenience of mechanisms that share account access with third parties.

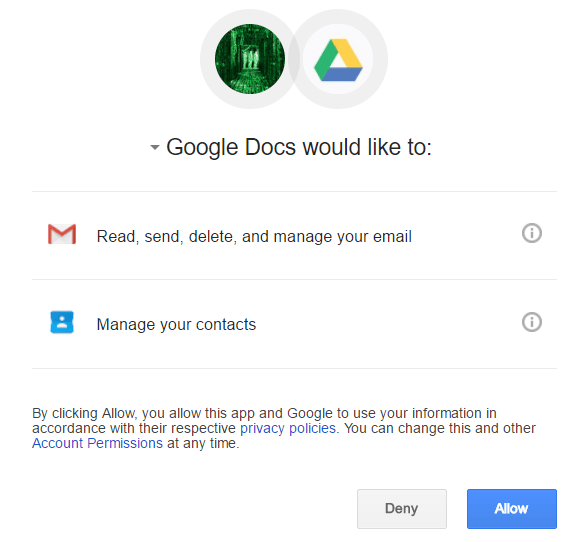

Many of the phishing messages came from contacts known to victims since part of the attack includes gaining access to contact lists. The messages claimed that someone wanted to share a Google Doc with the victim, and once the “Open in Docs” button in the email is clicked, the victim is redirected to a legitimate Google OAUTH consent screen where the attacker’s application, called “Google Docs” asks for access to victim’s Gmail and contacts through Google’s OAUTH2 service implementation.

OAUTH is a standard that allows the user to authorize account access to third-party applications through the exchange of an authorization token behind the scenes, rather then requiring a password from the user.

While the ruse was convincing in its simplicity, there were a number of red flags, including the fact that a Google service was asking for access to Gmail, and that the “To” address field was to an odd Mailinator account. Also, the developer information associated with the Google Docs malicious app was linked to a Gmail address connected to a Eugene Pupov. A Twitter account profile bearing that same Gmail address said Pupov was a Coventry (U.K.) student and tweets from the account yesterday claimed the emails were not a phishing attack, but a graduate final project. The Twitter account has been taken down, and a message to the Gmail account from Threatpost bounced back.

Bojan Zdrnja, a handler with the SANS Internet Storm Center, identified a number of spam domains involved, all with different TLDs for googledocs[.]g-docs[.]xxxx or googledocs[.]docscloud[.]xxxx. Many of those domains were taken down within 15 minutes of the first reports. Google also quickly updated Safe Browsing and Gmail with warnings about the phishing emails and attempts to steal personal information.

The phishing emails spread quickly on Wednesday and likely started with journalists and public relations professionals, each of whom are likely to have lengthy contact lists ensuring the messages would continue to spread in an old-school worm-like fashion. Researchers at Duo Security said today during a short Q&A hosted on YouTube that the scam was also particularly effective because it did not require email spoofing like traditional phishing campaigns. As designed, Wednesday’s attack bypassed all email security checks embedded in Gmail such as SPF and DKIM, which are designed to check sender reputations and prevent spoofing, said Duo analyst Trevor Sokley.

As for OAUTH, which experts point out has its shortcomings in terms of security and privacy, Google’s implementation doesn’t seem to be at fault, said the Duo researchers as well as Johannes Ullrich, dean of research at the SANS Institute.

Ullrich pointed out that people are used to the convenience of the Google OAUTH process, and failed to recognize the excessive behavior of the malicious Google Docs app.

“In this case, the OAUTH message did correctly state that the application asked for access to the user’s e-mail. This ‘should’ have been a tip off that the application wanted to do more than share a document,” Ullrich said. He added that Google could overtly bring publisher information forward to the user, which might help raise a red flag.

“From a user education perspective, it is important to emphasize the danger of sharing access with third-party applications, and to be sensitive if an application needs all the privileges it asks for,” Ullrich said. “This is also often abused for user profiling and monitoring (e.g. Facebook applications almost always try to get a list of your friends).”

OAUTH’s open nature allows anyone to develop similar apps. The nature of the standard and interaction involved makes it difficult to safely ask for permission without giving the users a lot of information to validate whether an app is malicious, said Duo’s Sokley.

“There are many pitfalls in implementing OAUTH 2.0, for example cross site request forgery protection (XSRF). Imagine if the user doesn’t have to click on the approve button, but if the exploit would have done this for you,” said SANS’ Ullrich. “OAUTH 2.0 also inherits all the security issues that come with running anything in a web browser. A user may have multiple windows open at a time, the URL bar isn’t always very visible and browser give applications a lot of leeway in styling the user interface to confuse the user.”