Sometimes vulnerability disclosure goes well — and sometimes it doesn’t. Security researchers still face legal action for “hacking” when reporting the bugs they find — as is the case with a flaw recently reported to the Giggle social network. However — while the vendor-researcher relationship is still fraught with pitfalls, the good news is that things are slowly starting to get better, say experts.

Notably, the Giggle news (detailed below) comes as releases of vulnerability-disclosure policies (VDPs) have snowballed, with names like Facebook and the U.S. government embracing transparent guidelines for ethical bug-hunting.

Giggle: No Laughing Security Matter

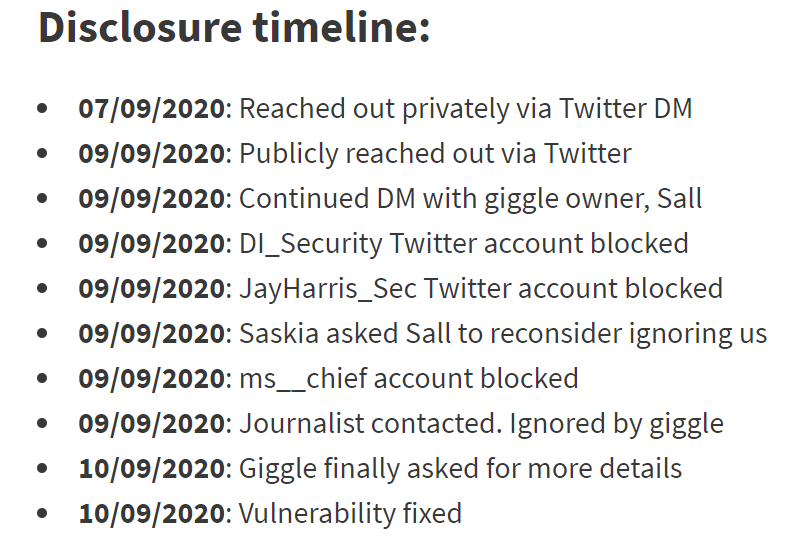

In a blog post on Thursday, Saskia Coplans, a founder at a majority-female security firm called Digital Interruption (DI), described a disclosure effort in which the company reached out to Giggle about a privacy flaw. Giggle, which bills itself as a social network “for girls,” offers various female-specific topic areas and communities, including those for victims of abuse and for sex workers. The down side is, according to its privacy policy, Giggle collects all kinds of information about users, including geolocation, personal preferences, demographic data and answers to surveys.

That’s a problem given that the bug that DI found would allow unverified attackers to trivially access this personal information on the platform from anywhere. To boot, the researchers found that the information was still accessible/stored even after a user deleted an account. DI researchers understandably felt it was important to report the issue to prevent exploitation by abusers and others.

The public tweet that started the furor.

So they did just that, first reaching out via Twitter in a direct message to the company. When there was no response after two days, DI published a public tweet directing the company and its founder, Australian screenwriter Sall Grover, to the DM. The researchers also mentioned the company’s perceived anti-trans stance — Giggle uses facial recognition and AI to determine if a user is female or not, which is a “test” many trans women can’t pass — and that’s when the problems began.

“Our public tweet had no engagement at all until Sall, the Giggle founder, decided to share a screenshot of it with her followers. We have since been subject to a tirade of abuse,” according to the blog. “Our three-year incorporated company has been accused of being a creepy bloke who runs private WhatsApp groups full of naked women, a front for the alt-left, making up the vuln to discredit Sall and her company, and hypocrites for wanting to protect the data of users despite the app’s founder having views that counter our own.”

Coplans added that none of the responses mentioned the actual security issue itself.

DI went on to attempt contact nonetheless, but was blocked at every attempt — the firm also asked Troy Hunt of HaveIBeenPwned the to plead its case to the company. Eventually, someone at Giggle did fix the bug.

“No one reached out,” Jahmel Harris, a DI founder and security researcher, told Threatpost. “Even though we sent Sall/Giggle some details right at the start of this, we don’t know if these weren’t passed to the [development team] as Sall (the owner) didn’t seem to understand what I was saying. Based on a recent email with the dev, it sounds like he figured it out based on some of the Twitter noise. We were only able to send full details and a proof of concept after Troy Hunt had asked Sall on our behalf if she would allow us to email her, but by this point it sounded like it had been fixed.”

Giggle has also threatened DI with legal action –though it’s unclear what the allegations will be.

“They’ve claimed they’ve sent all communications to a lawyer and I believe it’s because we published a blog post, not for finding the vulnerability,” Harris said. “I should note that we only published after the issue was fixed.”

Threatpost has contacted Giggle and asked for comment, but as of press time, there has been no response.

Noted vulnerability-disclosure expert and CEO at Luta Security, Katie Moussouris, weighed in on Twitter, calling the disclosure experience the “worst of the year.”

https://twitter.com/k8em0/status/1304062331773566976

VDPs to the Fore

As the Giggle debacle demonstrates, researchers are still being sued on occasion. Yet at the same time, this level of difficulty is a rarity, according to DI’s Harris.

“Honestly…it’s becoming easier to report vulnerabilities to companies now that we have Katie Moussouris and companies like HackerOne and Bugcrowd putting in a lot of effort to protect security researchers,” he told Threatpost. “We’re always going to see companies act like this, but changes in the law can go a long way helping report issues and vulnerability-coordination and bug-bounty platforms will often act as a mediator. This is the first time we’ve had an experience as intense as this. Mostly companies that don’t have much experience with this will at least be thankful we’re disclosing privately. It’s easy to understand this can be a fairly scary experience for a company, but if there is a defined way to respond to security researchers or vuln hunters, it’s often a case of fixing the vuln, thanking them and moving on.”

To that end, Facebook, the State of Ohio, a top voting-machine vendor and the U.S. federal government have all embraced VDPs in recent days — showing that the ethical hacking landscape is indeed improving.

By way of definition, VDPs are the latest step for many in the evolution of the vendor-researcher relationship. The industry has seen the rise of bug-bounty programs that pay researchers for their work; and there have also been more safe-harbor policies put into place to protect researchers from legal action. And, responsible disclosure policies have rolled out at many organizations, meant to protect vendors and avoid the disclosure of flaws before there are patches available. A VDP collects all of these factors and more into a centralized, written policy on dealing with disclosures.

Illustrating this, last week, Facebook rolled out a VDP that clarifies how Facebook bug-hunters will deal with flaws that they find in third-party software and open-source projects. Specifically, the tech giant said that it will implement a 90-day policy between a bug being reported and going public. At the same time, Facebook-owned WhatsApp debuted a security disclosure page that will act as a central repository for any bugs found in that platform.

“Facebook’s VDP addresses vulnerabilities of third parties, which helps to normalize vulnerability disclosure,” security researcher and bug-hunter Mike Takahashi told Threatpost. “If those contacted are responsive, it should only benefit them to receive these reports. Inevitably there will be examples where organizations are not responsive or aren’t taking reasonable steps to fix the vulnerabilities. When this happens there will be growing pains from the ensuing chaos of publicly disclosed vulnerabilities without a fix in place. This will open the door for black-hat hackers to exploit a vulnerability which they may not have known about otherwise, but also gives organizations an opportunity to be proactive with their own mitigations before an official fix is released.”

There have also been recent moves around election infrastructure; in August, Ohio’s secretary of state issued a VDP to cover the state’s election-related websites, the first such move by a state; and, Election Systems & Software, the biggest vendor of U.S. voting equipment, issued a VDP last month covering ES&S’s corporate systems and public-facing websites (though not voting machines and other equipment that’s already deployed in the field).

“It’s becoming more mainstream and more tech companies are starting to understand this is just part of the ecosystem,” DI’s Harris said.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) has mandated that federal agencies must implement VDPs by next March, which would give ethical hackers clear guidelines for submitting bugs found in government systems – and hopefully encourage more bug-hunting overall.

CISA’s announcement also drew praise from the bug-bounty community.

“The government is leaping ahead of much of corporate America…We will look back on this moment years from now to recognize it as a turning point in America’s fight for trustworthy technology.” Alex Rice, CTO and co-founder HackerOne, told Threatpost via email. “HackerOne believes that CISA’s Binding Operational Directive is a pivotal milestone in the mission to restore trust in digital democracy and protect the integrity of federal information systems. Every organization, especially those protecting sensitive information, should have a public-facing way to report potential security gaps. Collaboration with the hacker community provides a crucial advantage: having someone on your team who thinks like an attacker.”

Casey Ellis, CTO at ethical hacking platform Bugcrowd, added: “Those who have both the skills and altruistic interest to identify cyber-risk and improve the safety and security of the internet have been waiting patiently for the better part of 30 years [for acceptance], and our efforts to help have been met with varying responses.” In an August filing with CISA, he noted, “Up until five or six years years ago many of them were fearful, hostile and negative. The evolution of the information attack surface and the capabilities of our adversaries have caused a huge shift: The internet realized that all “hackers” aren’t burglars, many of them are actually locksmiths.”

VDPs in Context

While the VDP moves are net positives for cybersecurity, the juxtaposition of VDP rollouts with Giggle issue shows that VDPs aren’t simply a blanket golden ticket to a harmonious vendor-researcher relationship, researchers noted. There are many things that can go wrong if the policy doesn’t provide enough transparency and clarity.

For instance, less scrupulous researchers may publish details on a zero-day bug or even proof-of-concept exploits for unpatched issues without coordinating with a vendor, even if the vendor has a VDP and bounty program in place. Such was the case with SandBoxEscaper, who published a spate of zero-day exploits for Microsoft bugs in 2018 and 2019.

On the flip side, vendors may not respond to a report, leaving researchers in a tough situation. Some providers and vendors, like Giggle, don’t want to deal with the issue at all; but others may not provide full patches in a timely fashion. For instance, recently researchers disclosed bugs in Grandstream products for small- and medium-sized businesses even though the issues weren’t fully patched, after the firm’s 90-day disclosure window expired.

The Facebook VDP allows for a raft of exceptions to its 90-day window, including reserving the right to disclose a bug if a vendor doesn’t respond within 21 days of a report being filed.

“An issue that could be improved is vulnerability remediation speed; the industry standard is often 90 days from disclosure to being made public,” Charles Ragland, security engineer at Digital Shadows, told Threatpost. “There are many high-profile instances where patches either weren’t released or were barely released within this 90-day window. That’s a long time for an exploitable vulnerability to be exposed, and it’s likely that if one person figured it out, someone else will, too.”

Different researchers also may have different policies on the latter scenario, potentially leading to confusion as vendors juggle multiple reports from multiple parties with different timelines.

“Whether or not you have an official VDP, it can be a challenge is keeping up with outside reports,” Takahashi said. “This includes being responsive in communication with white-hat hackers and fixing any vulnerabilities. In the two years we’ve seen a huge increase in security issues in the news stemming from mismanagement of vulnerability disclosure. If vulnerability disclosures aren’t taken seriously, they can end up being very costly when they’re publicly disclosed.”

Vendors also need to balance many factors in developing and testing patches, according to Brian Gorenc, senior director of vulnerability research for Trend Micro and head of Zero Day Initiative (ZDI).

“Severity is one of those factors, and researcher may judge severity differently than the vendor,” he told Threatpost in an email interview. “Alternatively, there are times when vendors want to ignore or downplay certain reports and focus on developing new products. There needs to be more understanding on the process on both sides to prevent confusion – and that confusion leads to distrust and hard feelings.”

DI’s Harris also noted the true downsides if companies don’t embrace VDPs and other ethical-hacking measures.

“We understand people have great ideas and want to create applications to meet that need, but it can be very dangerous to move ahead with some of those ideas without getting proper security advice and support,” he told Threatpost. “If [Giggle] had been built with security in mind from the start, they could have still achieved what they wanted to do without putting vulnerable women in danger. Sall disregarded our report, putting the users of the application at risk and denied that a vulnerability was present without investigating. In our opinion, this is a breach of trust. By making it into a ‘fight’ between them and us, they actually encouraged others to look for the vulnerability. We wouldn’t be surprised if, unfortunately, it was exploited before it was fixed because of the way Sall and Giggle responded.”

Best Practices

Transparency with both the researcher and the public is a crucial factor to minimizing distrust and making VDPs effective, and Gorenc noted that there are industry best practices that should also be followed. These are laid out in the ISO 29147 standard, which includes guidance for both filing reports and receiving them. For instance: Providing clear boundaries for security researchers in terms of ethical hacking; offering clarity on what is in scope and what’s not; and specifying how long a researcher must wait before disclosing publicly, even if there is no patch available.

“Having a well-defined vulnerability disclosure policy is definitely something every agency receiving bug reports should have,” Gorenc said, referring to the just-announced government mandate to implement VDPs at all agencies. “Let’s hope [CISA] follows the guidelines set out in ISO 29147 and establishes a robust program rather than just checking boxes to be in compliance.”

Getting companies interested in developing bug-bounty programs or even simply paying attention to independent researchers reaching out in good faith can still be difficult, Ragland noted, adding that “making the process difficult and obtuse burns people out and leads to more ignored vulnerabilities.”

Thus, independent bug-bounty programs – like those run by HackerOne, Bugcrowd or ZDI – can help vendors by providing them access to an established VDP and bounty program.

“Vendor-agnostic bug-bounty programs can serve as intermediaries and provide an honest broker for researcher and vendor alike,” Gorenc said. “For example, with our program, researchers know their report won’t be ignored. At the same time, vendors know a report from us won’t go public unless our 120-day timeline is disregarded.”

Overall, expectations need to improve – both for researchers and vendors – and appropriately structured VDPs can be a big key to that, he said.

“There are still too many ‘surprises’ in vulnerability disclosure,” Gorenc noted. “Researchers are surprised by a vendor’s response (or lack thereof), and vendors are surprised by a researcher’s disclosure. We as an industry have been doing disclosure long enough that there should be no surprises.”

On Wed Sept. 16 @ 2 PM ET: Learn the secrets to running a successful Bug Bounty Program. Register today for this FREE Threatpost webinar “Five Essentials for Running a Successful Bug Bounty Program“. Hear from top Bug Bounty Program experts how to juggle public versus private programs and how to navigate the tricky terrain of managing Bug Hunters, disclosure policies and budgets. Join us Wednesday Sept. 16, 2-3 PM ET for this LIVE webinar.