A new family of point-of-sale malware, dubbed PinkKite, has been identified by researchers who say the malware is tiny in size, but can delivered a hefty blow to POS endpoints.

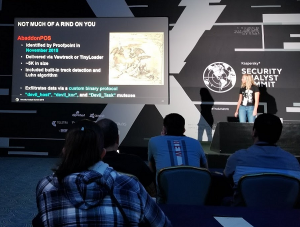

Researchers at Kroll Cyber Security first identified PinkKite in 2017 during a nine-month investigation into a large POS malware campaign that ended in December. The campaign is believed to be the first instance of PinkKite identified, according to researchers Courtney Dayter and Matt Bromiley, who presented their findings at Kaspersky Lab’s Security Analyst Summit on Friday.

PinkKite is less than 6k in size and similar to other small POS malware families such as TinyPOS and AbaddonPOS. Similar to those small-sized malware families, PinkKite uses its tiny footprint to avoid detection and comes equipped with memory-scraping and data validation tools.

“Where PinkKite differs is its built-in persistence mechanisms, hard-coded double-XOR encryption (used on credit card numbers) and backend infrastructure that uses a clearinghouse to exfiltrate data to,” Dayter said.

Criminals behind the PinkKite campaign used three clearinghouses (or depots) located in South Korea, Canada and the Netherlands to send data to. Typically, POS malware sends data directly to a C2 server.

“From a malware collection point of view, it was probably easier for adversaries to send data to clearinghouses. It also may have helped them keep a little bit of distance from the POS terminals,” Bromiley said. “But, from an investigative point of view we loved it because it made the operation very noisy.”

PinkKite’s executable naming convention attempted to masquerade as a legitimate Windows program with names such as Svchost.exe, Ctfmon.exe and AG.exe. In all, Kroll identified several PinkKite families. “A white list version (of PinkKite) had a list of processes it was specifically targeting. The black list version had a list of processes it was specifically ignoring,” Bromiley said.

PinkKite’s executable naming convention attempted to masquerade as a legitimate Windows program with names such as Svchost.exe, Ctfmon.exe and AG.exe. In all, Kroll identified several PinkKite families. “A white list version (of PinkKite) had a list of processes it was specifically targeting. The black list version had a list of processes it was specifically ignoring,” Bromiley said.

Once the credit card data was scraped from system memory, PinkKite uses a Luhn algorithm to validate credit and debit card numbers. To further frustrate analysis and detection, PinkKite adds another layer of obfuscation via a double-XOR operation that encodes the 16 digits of the credit card number with a predefined key. Next, credit card data is stored in compressed files with names such as .f64, .n9 or .sha64. Those records can contain as many as 7,000 credit card numbers each and are periodically sent manually using a separate Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) session to one of the three PinkKite clearinghouses.

“Once the data was scraped by PinkKite, it was written to a file on a remote system. These remote ‘collection’ systems served as central collection points (clearinghouses) for hundreds or thousands of malware output files,” Dayter said.

Kroll isn’t sharing many details regarding the group behind PinkKite, beyond the infection technique used to plant the POS malware on endpoints. According to researchers, the hackers likely infiltrated one main system and then from there used PsExec to move laterally across the company’s network environment. Hackers then identified the Local Security Authority Subsystem Service (LSASS) and extracted credentials using Mimikatz. Once systems were compromised, attackers would swoop in to remove the credit card data via the RDP session.

Dayter and Bromiley said they were tipped off to the infection because the client had been made aware that its customer’s credit cards were being sold on the black market. The name PinkKite follows Kroll’s malware naming convention, and was randomly selected, according to the company. There are no ties to the malware’s name and the malware itself.