It appears that the free ride is over for software vendors.

For years, software makers have benefited from the work done by the community of security researchers who spend days or weeks looking for vulnerabilities and novel ways to break the vendors’ products. This work is virtually always done pro bono by researchers who either have day jobs and do their research as a sideline or by experts at security companies who do the work as a way to promote their research teams. Either way, until recently, most of these bug reports were given to the affected vendors for free.

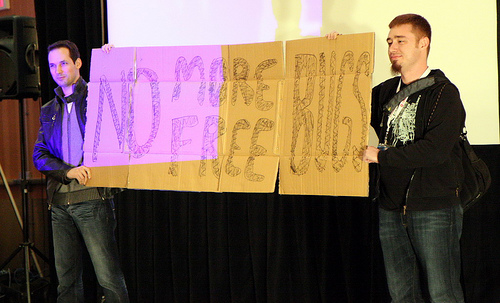

But now, several high-profile bug finders are trying to put an end to this practice. Alex Sotirov (above, left), Dino Dai Zovi (above, right) and Charlie Miller were talking up their “no more free bugs” mantra at the CanSecWest conference last week, spreading the word that, in most cases, they would no longer be providing vendors with free vulnerability notices. Miller, of Independent Security Evaluators, is already pretty far down this road, having turned his skills into a career finding bugs for money. And he’s put those skills to use to win cash bounties at the Pwn2Own hacking contest at CanSecWest the last two years.

In an interview with my colleague Ryan Naraine last week, Miller said there is a very clear and definable market value for bugs now, thanks to the development of bug-buying programs from TippingPoint’s Zero Day Initiative and VeriSign’s iDefense division.

“I was shocked when I saw someone sign up to go after IE 8 [at CanSecWest]. You can get paid a lot more than $5,000 for one of those bugs. I’ve talked to a lot of smart, knowledgeable people and no one knows exactly how he did it. [Nils] could easily get $50,000 for that vulnerability. I’d say $50,000 is a low-end price point,” Miller said. “For the amount of time he spent to do what he did on IE and Firefox, he could have found and exploited five or 10 Safari bugs. With the way they’re paying $5,000 for every verifiable bug, he could have spent that same time and resources and make $25,000 or $30,000 easily just by going after Safari on Mac.”

Several researchers said that reliable, remote exploits for high-profile applications such Internet Explorer can bring as much as $100,000. Dai Zovi and Sotirov are both independent security researchers and it’s clearly in their interest to condition vendors to the practice of paying for bugs. In a blog post, Dai Zovi said in addition to the monetary incentives, there are legal and practical reasons for not simply giving bugs away.

- Reporting vulnerabilities can be legally and professionally risky. When a researcher discloses the vulnerability to the vendor, there is no “whistle blower” protection and independent security researchers may be unable to legally defend themselves. You may get threatened, sued, or even thrown in jail. A number of security researchers have had their employers pressured by vendors to whom they were responsibly disclosing security vulnerabilities. Vendors expect security researchers to follow responsible disclosure guidelines when they volunteer vulnerabilities, but they are under no such pressure to follow responsible guidelines in their actions towards security researchers. Where are the vendors’ security research amnesty agreements?

- It is unfair to paying customers. Professional bug hunting is a specialized and expensive business. Software vendors that “freeload” on the security research community place their customers at risk by not putting forth resources to discover vulnerabilities in and fix their products.

Fair points. But for this discussion, it’s probably unnecessary to go beyond the financial argument. These researchers are performing a service by improving the quality and security of the vendors’ products, and it’s a service that has a clear market value. If an affected vendor isn’t interested in paying for a vulnerability, so be it. The researcher can then try to sell it to ZDI, iDefense, a government agency or other buyer. But the vendors shouldn’t expect the bug finder to just hand over the details gratis.

Those days are gone.

Photo credit: Garrett Gee’s Flickr photostream (Creative Commons 2.0)